On-chain Privacy and Financial Compliance

A framework for evaluating privacy regimes, compensating controls, and stakeholder needs

.png)

<span class="premium-content_chapter">PART 1</span>

Executive summary

On-chain finance is approaching an inflection point. Privacy is increasingly necessary for user safety, market integrity, and mainstream adoption — while anti-money laundering (AML) / countering the financing of terrorism (CFT) regulations and national security objectives require data-accessibility, speed, and the ability to act.

The policy question is no longer "privacy versus compliance." It’s: Which privacy regime — combined with which compliance model and which governance controls — can meet the minimum needs of all stakeholders?

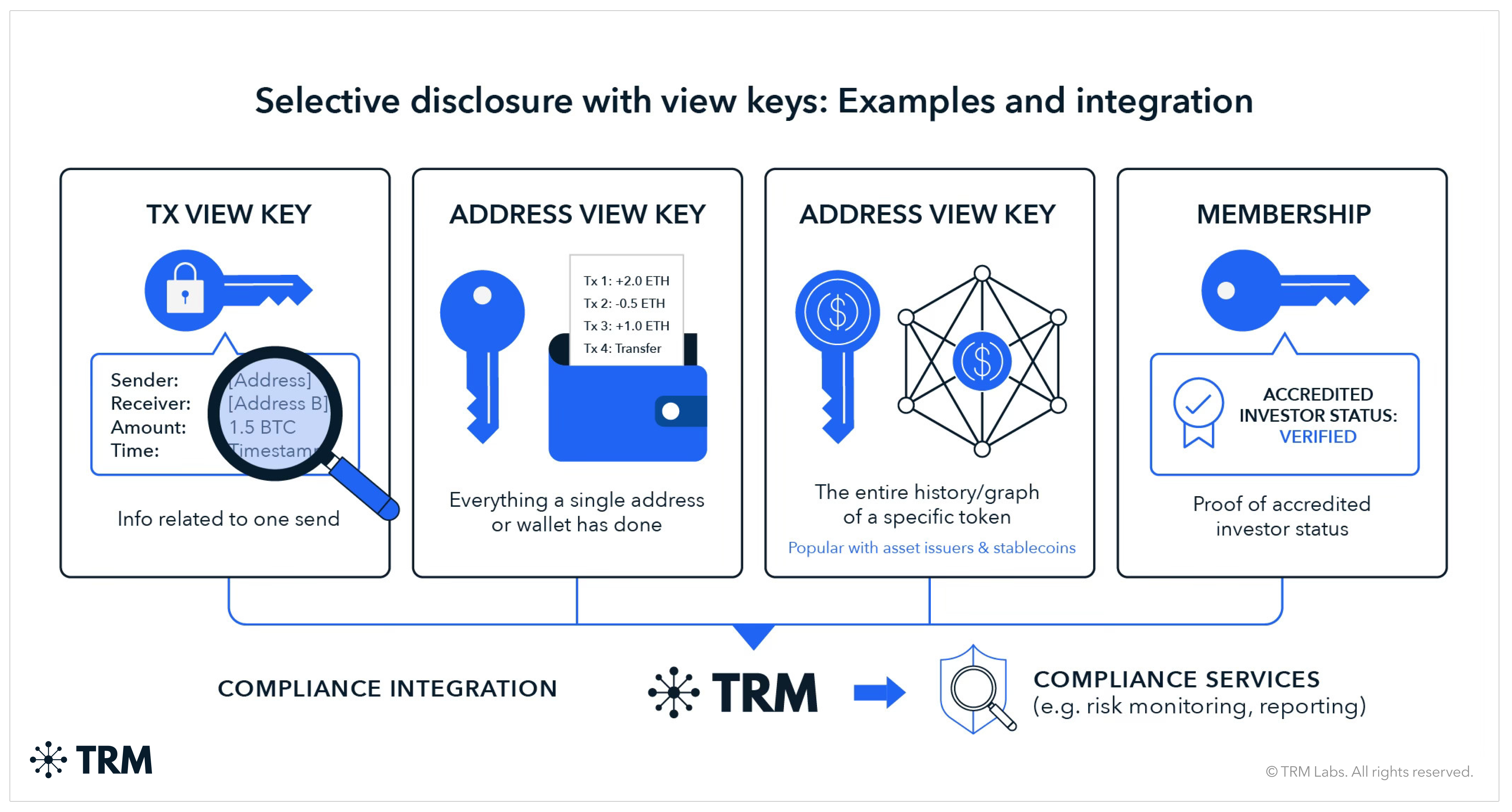

This paper provides a framework for evaluating five privacy regimes common in privacy-preserving blockchain systems:

- Transaction view keys (per-transaction disclosure)

- Address view keys (wallet-scoped disclosure)

- Set membership proofs (compliance status attestation)

- Asset view keys (asset-scoped visibility)

- Allow-list models (permissioned transacting)

Each regime creates different residual risks for end users, service providers, regulators, law enforcement, and protocol issuers. None eliminates risk entirely, but no AML regime does — nor is that the standard, which is typically “reasonably risk-based.” This paper therefore evaluates compensating controls, including KYC requirements, time delays, value/volume/velocity limits, and asset convertibility constraints.

Key findings

- No single privacy regime satisfies all stakeholder needs. Hybrid approaches combining asset-level visibility with conversion constraints and tiered access controls offer the most promising path forward.

- Compensating controls vary significantly in compliance utility. Know Your Customer (KYC) on addresses provides attribution but creates data security and adoption tradeoffs. Time delays and velocity limits provide interdiction value but degrade market function.

- Governance and key custody are as important as the privacy regime itself. Who holds keys, under what access controls, and with what due process protections will determine whether any regime is trustworthy in practice.

The paper concludes with recommendations for regulators, industry participants, and protocol/asset issuers.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

<span class="premium-content_chapter">PART 2</span>

Background and definitions

What "on-chain privacy" means

"Privacy" in blockchain systems is not a single property, but rather can be decomposed into the type of information that is cryptographically hidden:

- Pseudonymity: Addresses unlinkable to identity, but transactions visible

- Confidentiality: Transaction amounts hidden; transaction graph visible

- Anonymity: Transaction graph hidden; amounts may be visible

- Full privacy: Both amounts and graph hidden

Selective disclosure is the ability to reveal specific information to authorized parties without revealing everything:

- Transaction view keys (per-transaction disclosure)

- Address view keys (wallet-scoped disclosure)

- Asset view keys (asset-scoped visibility)

- Set membership proofs (compliance status attestation)

For each disclosure regime, the choice of enforcement layer has significant implications for evasion resistance: protocol-level enforcement is hardest to circumvent (would require moving to a different chain), while application-level enforcement is easiest (use a different front-end or interact directly with contracts).

Different blockchain architectures provide different defaults. Bitcoin and Ethereum are pseudonymous but publicly auditable: every transaction is visible, and sophisticated analytics can often link addresses to identities. Privacy-preserving chains (e.g. Zcash, Monero, Iron Fish, Aleo, Canton, Railgun, Privacy Pools, and others) use cryptographic techniques to shield some or all of this information by default, with optional or mandatory disclosure mechanisms.

This paper focuses on systems where privacy is the default and disclosure is selective — the harder case for compliance design.

Why privacy is necessary

When someone pays with a credit card or bank transfer, the merchant sees only what's necessary for the transaction. The merchant doesn't see the customer's total bank balance, other purchases, employer, or spending history. Privacy is the default; disclosure is selective and consent-based.

When someone pays with bitcoin or ether, anyone who knows the sender's address can see their entire transaction history, estimate their total holdings across linked addresses, and track their future activity indefinitely. This is a regression from traditional financial privacy, not an improvement.

Privacy as consumer protection

Default privacy is a consumer protection issue. Regulators concerned with consumer protection should recognize that transparent blockchains may expose users to harms that traditional financial systems do not.

- In 2019 and 2020, multiple cryptocurrency holders received extortion emails referencing their exact wallet balances — information that could only have come from blockchain analysis. A database maintained by security researcher Jameson Lopp documents over 100 known physical attacks on cryptocurrency holders, many of whom believe they were targeted based on on-chain wealth visibility.

- Blockchain transparency can expose salary payments, donations to political causes, purchases of legal but sensitive goods, and relationship patterns. For individuals in vulnerable situations such as domestic abuse survivors or political dissidents, this exposure can be dangerous.

The institutional imperative

Beyond individual users, institutions require privacy to operate on-chain:

- Payment confidentiality: Businesses cannot conduct payroll, vendor payments, or treasury operations on systems where competitors can observe every transaction

- Trading confidentiality: Market makers and institutional traders cannot operate where their positions and order flow of tokenized assets are publicly visible

- Regulatory requirement: Privacy regulations like GDPR may actually require transaction confidentiality in certain contexts

AML/CFT objectives and the privacy-security balance

The Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) requires financial institutions to act as the first line of defense by filing Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs). With FinCEN receiving over four million SARs annually, these reports are the cornerstone of US financial intelligence.

However, the utility of a SAR relies entirely on context. SARs are investigative leads — not conclusions — whose value is derived from an analyst’s ability to identify patterns across transactions and expand the investigation graph ("following the money").

This creates a tension with privacy design. A privacy regime that creates total opacity, preventing institutions from linking counterparties or spotting deviations in behavior, does not just hide user data; it breaks a fundamental mechanism of AML enforcement.

The balance is to design privacy solutions that protect sensitive user data from public exposure without blinding the investigative mechanisms required to detect crime.

FATF and the global balance

This tension extends to the global stage. The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) sets standards that explicitly require identity data to move alongside funds (the "Travel Rule"). FATF has repeatedly flagged that permissionless systems and unhosted wallets create structural privacy challenges by allowing funds to move outside regulated perimeters.

For US policy to align with this global framework, privacy technologies must balance these baseline obligations. Divergence creates regulatory arbitrage, complicating cross-border enforcement and risking the legitimacy of the asset class.

{{31-on-chain-privacy-and-financial-compliance-callout-1}}

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

<span class="premium-content_chapter">PART 3</span>

Why crypto rails change compliance

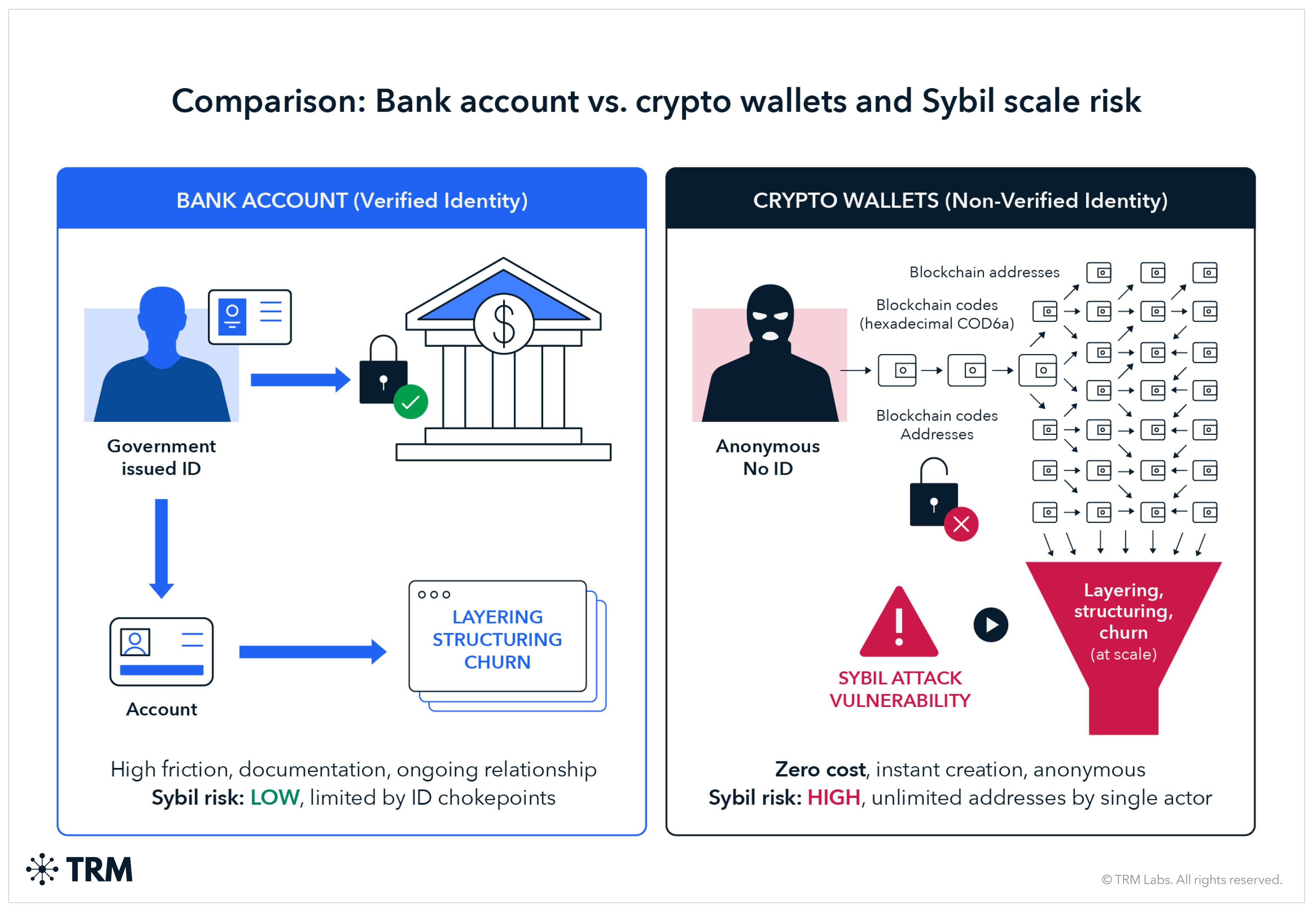

Traditional AML controls assume certain structural features: account opening with customer identification, relationship management, transaction monitoring within institutional perimeters, and friction that slows the movement of large values. Permissionless blockchain systems break these assumptions in three fundamental ways.

Permissionless access

Anyone can join and transact on a public blockchain without being identity-checked. There is no "account opening" process at the network layer. This shifts AML controls from network gatekeeping to edge enforcement — regulated entities (exchanges, custodians, payment processors) become the compliance perimeter.

The problem: funds can originate from, pass through, and terminate at addresses outside any regulated perimeter. FATF has identified this as a persistent coverage gap. And the result is that compliance becomes probabilistic rather than comprehensive.

Sybil scale

The marginal cost of creating a new blockchain address is effectively zero. A single actor can control thousands or millions of addresses. This enables:

- Layering at scale: Moving funds through many hops to obscure origin

- Structuring: Breaking large transfers into many small ones

- Counterparty churn: Rapidly cycling through fresh addresses to defeat pattern detection

By contrast, opening multiple bank accounts requires identity documentation, onboarding friction, and ongoing relationship management — natural chokepoints that limit Sybil attacks.

Speed and continuous settlement

Blockchain settlement is fast (occurring in seconds to minutes) and operates continuously (24/7/365). Adversaries can move funds across many hops in the time it takes a compliance team to review an alert. This pressures compliance systems toward real-time interdiction — or, at minimum, rapid detection with automated friction.

Several jurisdictions have responded by introducing mandatory delays or cooling-off periods for crypto withdrawals. South Korea, for example, has implemented withdrawal delay requirements for new accounts. These responses signal regulatory recognition that speed itself is a compliance challenge.

Implications

These structural differences mean that compliance on crypto rails requires:

- Edge enforcement rather than perimeter control

- Real-time or near-real-time systems rather than batch review

- New governance primitives (freezing, clawback, selective disclosure) that don't exist in traditional payment systems

- Probabilistic rather than deterministic coverage, with compensating controls to manage residual risk

{{31-on-chain-privacy-and-financial-compliance-callout-2}}

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

<span class="premium-content_chapter">PART 4</span>

Stakeholders and threat model

Stakeholder needs matrix

Threat model

Any privacy and compliance regime must account for the following threat categories:

External threats

- Hacks and exploits: Theft from protocols, bridges, or custodians, followed by rapid fund movement

- Sanctions evasion: State actors or sanctioned entities using privacy features to move value

- Layering and structuring: Criminal proceeds moved through many hops/addresses to obscure origin

Internal/governance threats

- Insider abuse: Employees or contractors with privileged access misusing data

- Key compromise: Cryptographic keys stolen, leaked, or coerced

- Escrow failure: Third-party key custodians breached, failing, or acting adversely

Systemic threats

- Regulatory arbitrage: Activity shifting to less-regulated venues or assets

- Data honeypots: Large stores of sensitive data becoming high-value targets

- Governance capture: Access mechanisms controlled by parties with misaligned incentives

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

<span class="premium-content_chapter">PART 5</span>

Disclosure regimes and compliance models

This section evaluates four disclosure regimes using a consistent framework. For each regime, we assess:

Evaluation rubric

Each regime and compensating control is evaluated on seven dimensions:

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">1. Transaction view key (per-transaction disclosure)</h3>

Overview

A transaction view key is a disclosure artifact scoped to a single transaction. It reveals the inputs, outputs, and relevant metadata for that specific transfer and nothing else.

This model is analogous to "proof of payment" mechanisms. Monero, for example, allows senders to generate a transaction key that proves payment to a specific recipient without revealing the sender's broader transaction history.

The key holder (typically the transacting user or the VASP facilitating the transaction) can selectively share visibility with regulators, law enforcement, or counterparties on a transaction-by-transaction basis.

.png)

{{31-on-chain-privacy-and-financial-compliance-callout-3}}

Access model

- Primary holder: The transacting party (user or VASP acting on their behalf)

- Access model: Disclosure is reactive — investigators or supervisors must request specific transaction proofs, and the key holder must produce them

- No persistent visibility: Without the key, the transaction remains opaque

Residual risks

Compensating controls

Governance and security

- Key lifecycle: Per-transaction keys are numerous and ephemeral, creating storage and retrieval challenges

- Evidentiary chain: Proving key authenticity and provenance for legal proceedings requires robust logging

- Insider risk: Relatively contained as compromise of one key exposes only one transaction

Compliance utility summary

{{31-on-chain-privacy-and-financial-compliance-callout-4}}

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">2. Address view key (wallet-scoped disclosure)</h3>

Overview

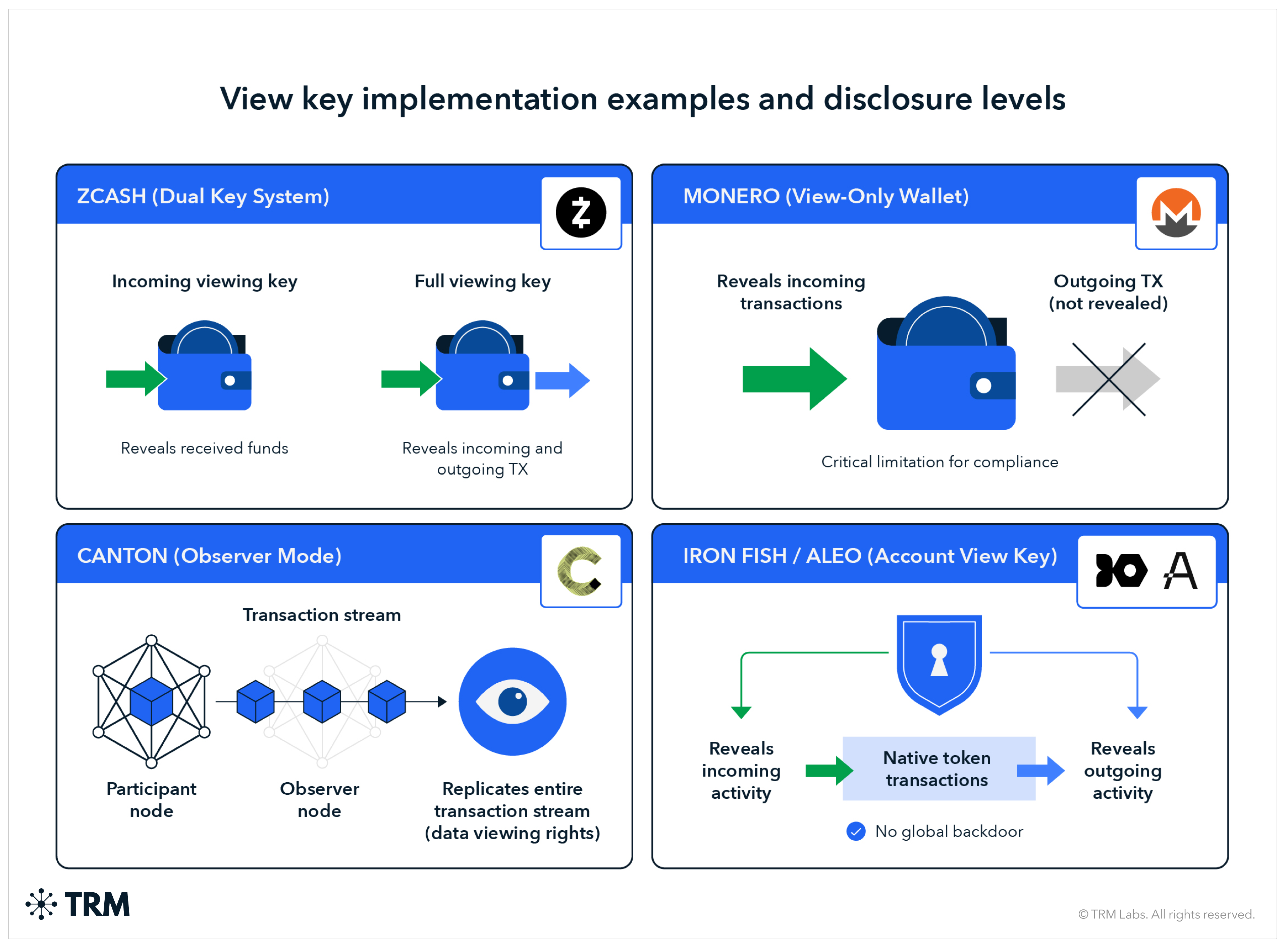

An address view key provides visibility into an address's transaction activity across time. Unlike per-transaction keys, this is a persistent disclosure mechanism — once shared, the key holder can observe all past and (depending on implementation) future transactions for that address.

Implementation varies significantly across protocols:

- Zcash distinguishes between incoming viewing keys (which reveal received funds) and full viewing keys (which reveal both incoming and outgoing transactions)

- Monero view-only wallets reveal incoming transactions but not outgoing — a critical limitation for compliance purposes

- Canton enables participants (i.e. “parties”) to replicate the entire transaction stream to another node in “observer” mode which provides data viewing (“observer”) rights

- Iron Fish and Aleo describe address/account view keys as revealing both incoming and outgoing activity with no global backdoor for native token transactions

For this analysis, we assume a "compliant address view key" that covers both incoming and outgoing transactions across all assets held at that address. Not all "view keys" are created equal, as the scope of visibility varies significantly.

{{31-on-chain-privacy-and-financial-compliance-callout-5}}

Access model

- Primary holder: The wallet owner or the VASP managing the wallet on behalf of a customer

- Access model: Key can be escrowed with a regulated custodian, shared directly with supervisors, or held solely by the user

- Persistent visibility: Once shared, the key provides ongoing access (unless the user migrates to a new address)

Residual risks

Compensating controls

Governance and security

- Key escrow models: Who holds address view keys — users only, VASPs, regulators, or independent custodians — determines the security and due process profile

- Rotation and revocation: Unlike per-transaction keys, address keys are long-lived; compromised keys require address migration

- Insider risk: Higher than per-transaction — a single compromised key exposes an entire account history

Compliance utility summary

{{31-on-chain-privacy-and-financial-compliance-callout-6}}

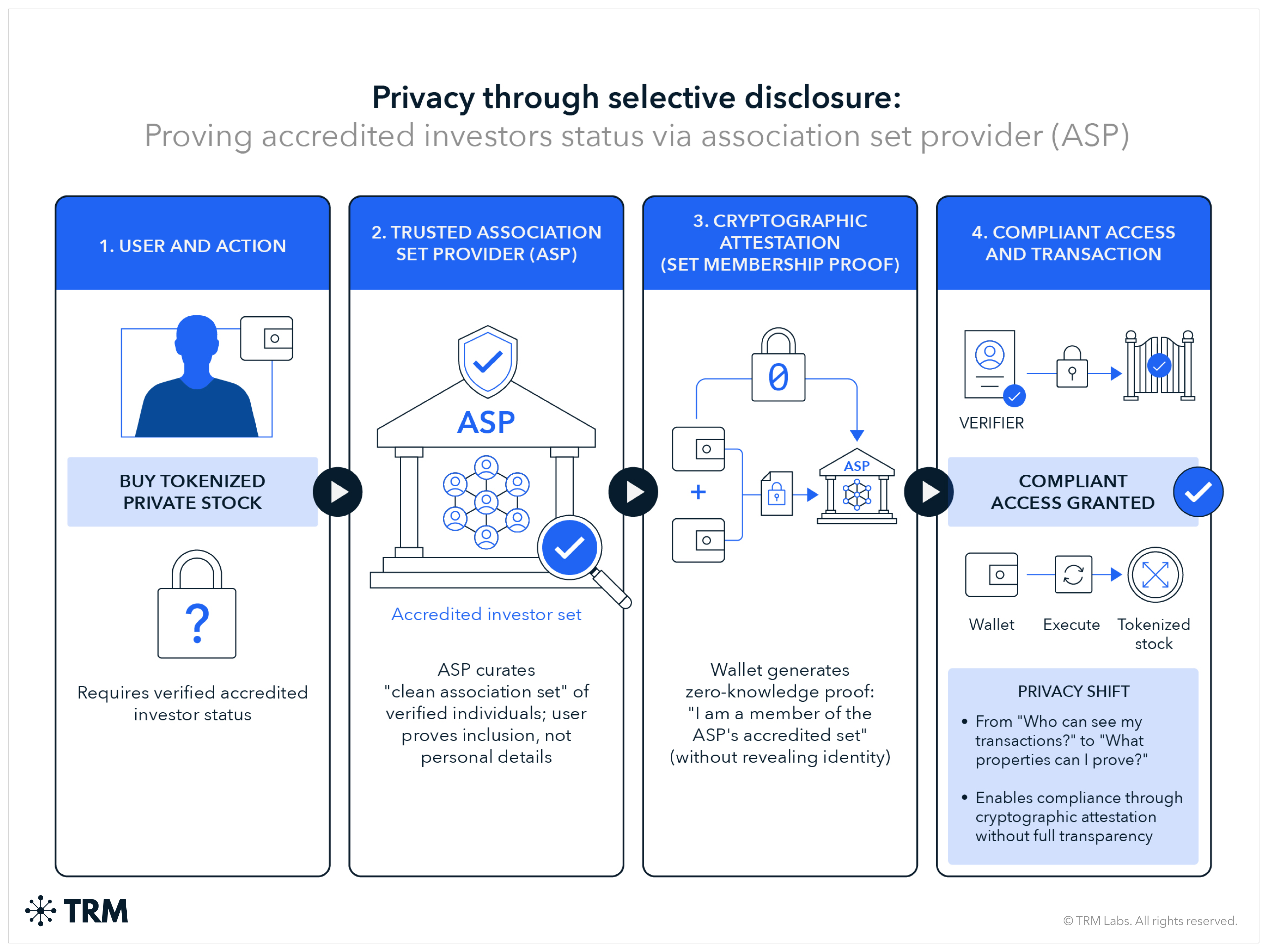

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">3. Set membership proofs (compliance status attestation)</h3>

Overview

Set membership proofs enable privacy-preserving compliance by allowing users to prove properties about their funds' origins without revealing specific transaction details. Two primary variants exist:

- Proof of Innocence (PoI), which uses exclusionary semantics

- Association Set Providers (ASP), which uses inclusionary semantics

In Proof of Innocence, a user proves — via zero-knowledge proof — that their funds do not intersect with a disallowed set (e.g. sanctioned addresses, known hacks, high-risk sources). The user demonstrates they are not one of the bad actors without revealing their specific deposit address.

In Association Set Provider models, a user proves that their funds do belong to an allowed set curated by a trusted ASP. Conceptually, ASP is membership "turned inside-out": rather than proving exclusion from a blacklist, users prove inclusion in a clean association set.

This is less a "full transparency regime" than a "selective disclosure regime that creates compliance through cryptographic attestation" — the relevant privacy question shifts from "who can see my transactions" to "what properties can I prove about my transactions without revealing them."

Access model

- Curator/set operator: In PoI, any party can publish exclusion lists (often based on public sanctions data or blockchain forensics). In ASP, designated providers curate allowed sets based on proprietary or public criteria.

- Access model: Users generate ZK proofs locally against the current set commitment. Counterparties or smart contracts verify proofs on-chain before accepting transactions.

- Set updates: Curators periodically update set commitments. In PoI, newly discovered illicit addresses are added to the exclusion list. In ASP, addresses found to be associated with illicit activity can be removed from the allowed set, and some designs include rage-quit/refund mechanisms for affected positions.

Residual risks

Compensating controls

Governance and security implications

- Curator accountability: Who is responsible if a curator fails to flag a known illicit address, or incorrectly flags a legitimate one? What standards govern curator operations, and what recourse exists for affected parties?

- Interoperability and fragmentation: Different curators, different accepted roots, and different verification requirements may create a fragmented ecosystem where users must navigate complex compatibility matrices.

- Contamination via ZK implementation faults: A critical limitation of Zero-Knowledge Proofs is the trade-off between privacy and auditability. If a zero-day vulnerability or logic bug is discovered within the ZK circuit, the protocol’s inherent anonymity makes it impossible to perform a retroactive forensic analysis. Consequently, even after patching, developers cannot distinguish between legitimate historical transactions and those that may have exploited the bug to forge transactions.

- PoI pool contamination: In Proof of Innocence systems, bad actors who deposit funds before their addresses are flagged permanently contaminate the anonymity pool. Even after the address is added to the exclusion list, the funds are already commingled, and users who withdrew during the contamination window may have unknowingly included tainted funds in their anonymity set.

Compliance utility summary

{{31-on-chain-privacy-and-financial-compliance-callout-7}}

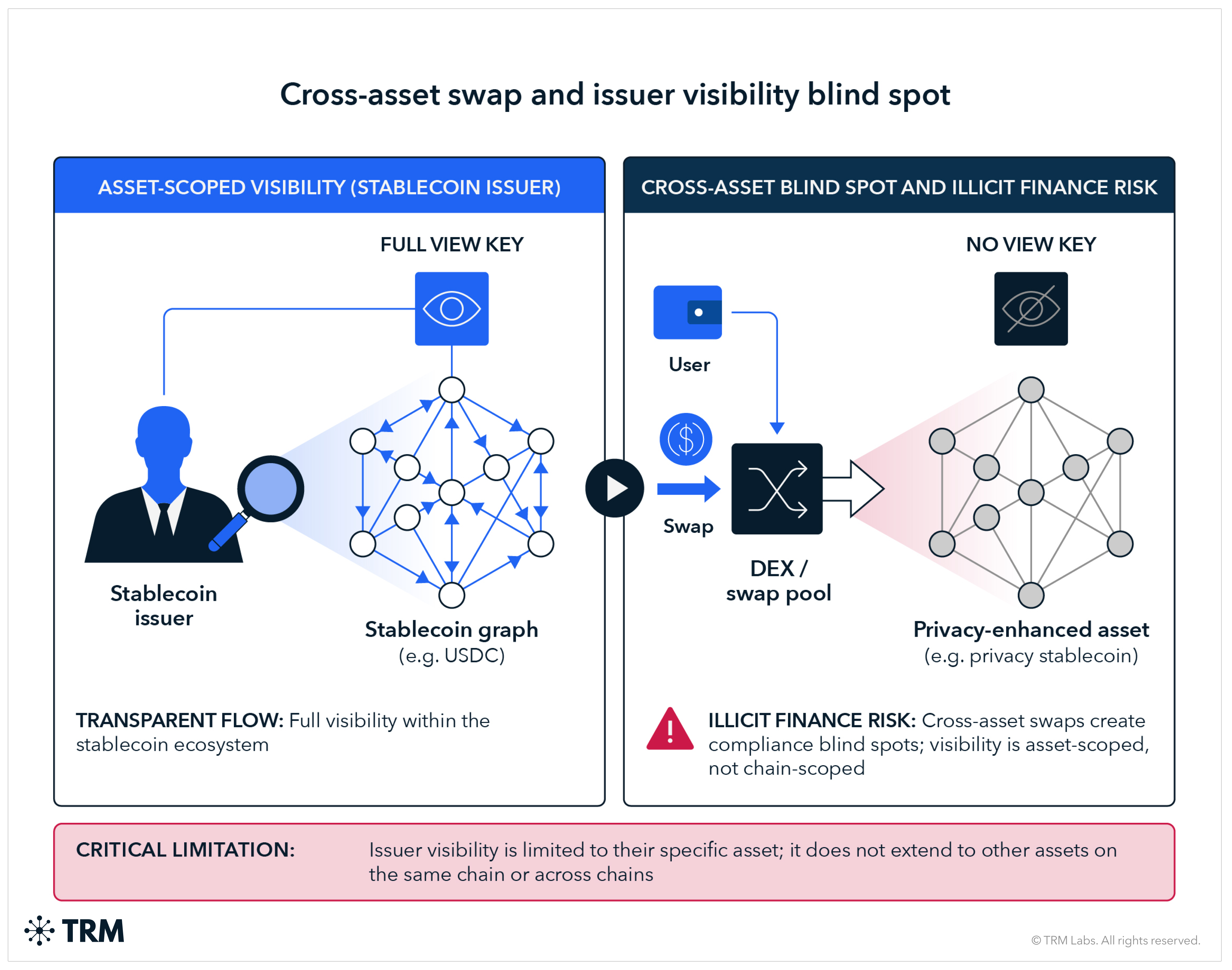

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">4. Asset view key (issuer-scoped visibility)</h3>

Overview

Under this model, the asset issuer holds a privileged key that provides visibility into all transactions involving that asset, without requiring user-by-user key sharing.

This is common in regulated stablecoin and tokenized asset models, where the issuer has compliance obligations and needs visibility to meet them. The issuer can monitor for suspicious patterns, respond to law enforcement requests, and (in some implementations) freeze or claw back funds.

Critical limitation: On multi-asset chains, issuer visibility is asset-scoped, not chain-scoped. If a user swaps from a compliant asset into a non-compliant asset, the issuer loses visibility. This creates cross-asset blind spots.

{{31-on-chain-privacy-and-financial-compliance-callout-8}}

Access model

- Primary holder: The asset issuer (or a delegated compliance agent)

- Access model: Issuer has persistent visibility by default; may delegate read access to regulators or law enforcement under agreed protocols

- User consent: Typically implicit in using the asset (terms of service) rather than per-transaction

Residual risks

Compensating controls

Governance and security

- Issuer as systemic custodian: The issuer holds keys to all user activity — a fundamentally different trust model than user-held or VASP-held keys

- Delegation and access control: How does the issuer grant access to regulators and law enforcement? Under what legal frameworks? With what logging and accountability?

- Continuity planning: What happens to visibility if the issuer is acquired, goes bankrupt, or is legally compelled to stop operating?

- Cross-border complexity: Issuer in jurisdiction A may face conflicting demands from jurisdictions B and C

Compliance utility summary

{{31-on-chain-privacy-and-financial-compliance-callout-9}}

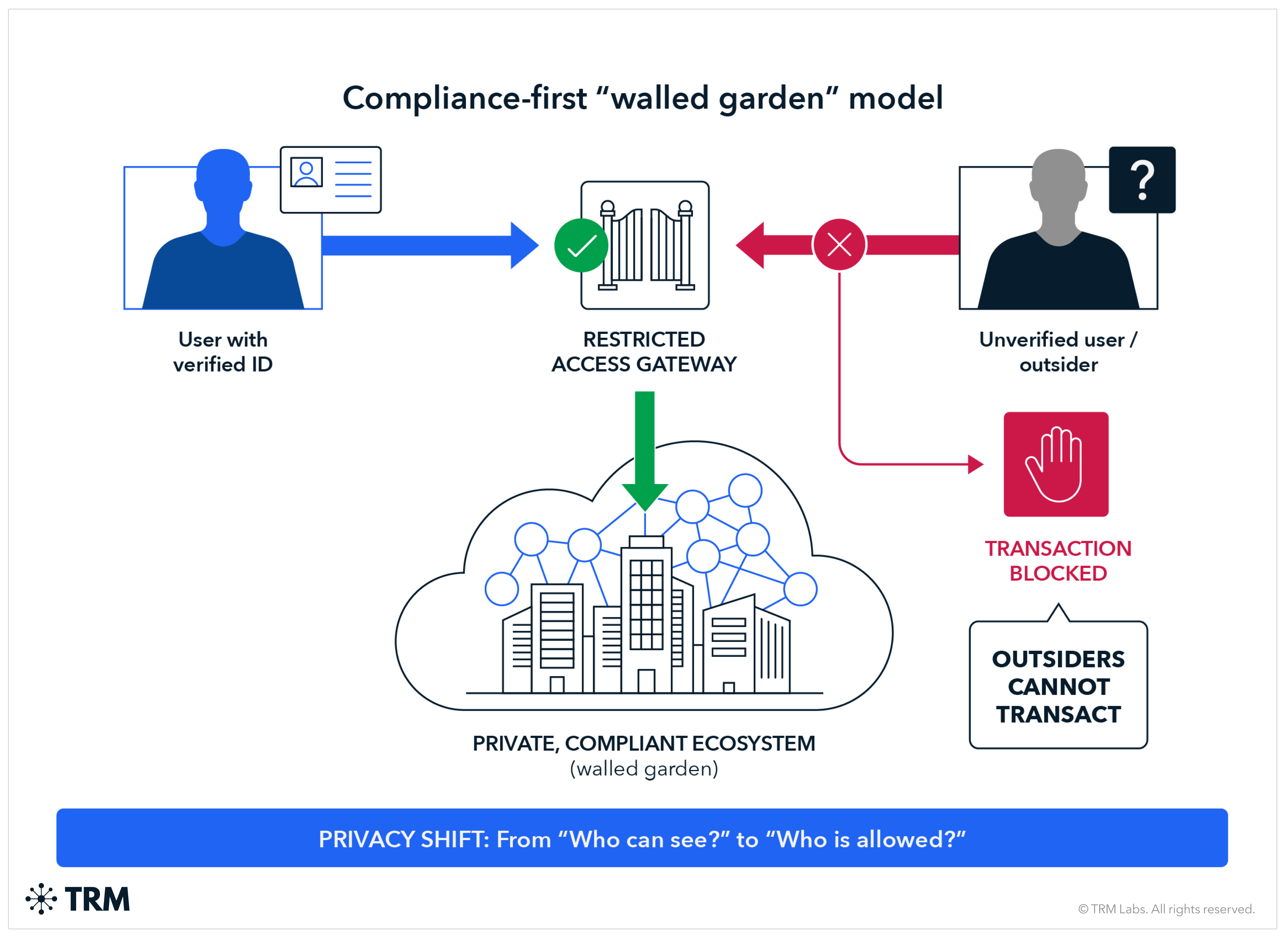

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">5. Allow-list model (permissioned transacting)</h3>

Overview

Under an allow-list model, only pre-approved addresses can hold or transact the asset. This is common for tokenized securities, other real-world asset (RWA) tokenizations, and institutional-only platforms.

Rather than relying on cryptographic privacy with selective disclosure, this model achieves compliance through access control: only vetted participants can enter the system, and all transactions occur between known counterparties.

This is less a "privacy regime" than a "compliance regime that creates privacy through restricted access and observability.” Outsiders cannot transact, so the relevant privacy question shifts from "who can see my transactions" to "who is allowed to be my counterparty."

Access model

- Gatekeeper: The asset issuer or a designated registry operator maintains the allow-list

- Access model: Prospective holders must complete KYC/accreditation before being added; transactions between non-listed addresses fail at the asset level

- Ongoing monitoring: The issuer can remove addresses from the allow-list, effectively freezing their ability to transact

Residual risks

Compensating controls

In the allow-list model, the allow-list itself is the primary control. Additional measures include:

Governance and security implications

- Centralized control: The issuer has significant power over who can participate, creating both accountability and abuse potential

- Due process: What recourse does an address holder have if removed from the allow-list? What standards govern removal? Which sanctions list applies?

- Continuity: If the issuer fails, who maintains the allow-list? Can the asset continue to function?

- Interoperability: Allow-listed assets may have limited utility in broader DeFi ecosystems

Compliance utility summary

{{31-on-chain-privacy-and-financial-compliance-callout-10}}

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

<span class="premium-content_chapter">PART 6</span>

Cross-cutting governance and security

Regardless of privacy regime, certain governance and security considerations apply across all models.

Key custody and data security

Custody models

The security profile of any privacy regime depends heavily on who holds disclosure keys:

Breach impact analysis

For each regime, stakeholders should ask: If the key custodian is compromised, what is exposed?

- Transaction view key: One transaction per key

- Address view key: Entire account history for that address

- Asset view key: All users of that asset

- Allow-list database: All participant identities (but not necessarily transaction details beyond what's on-chain)

Key loss and destruction

Policy must address:

- Operational impact: Can investigations proceed if keys are lost or destroyed?

- Retention requirements: How long must keys be retained?

- Penalties: What are the consequences for failing to produce keys when legally required?

- Recovery mechanisms: Are there backup or recovery procedures?

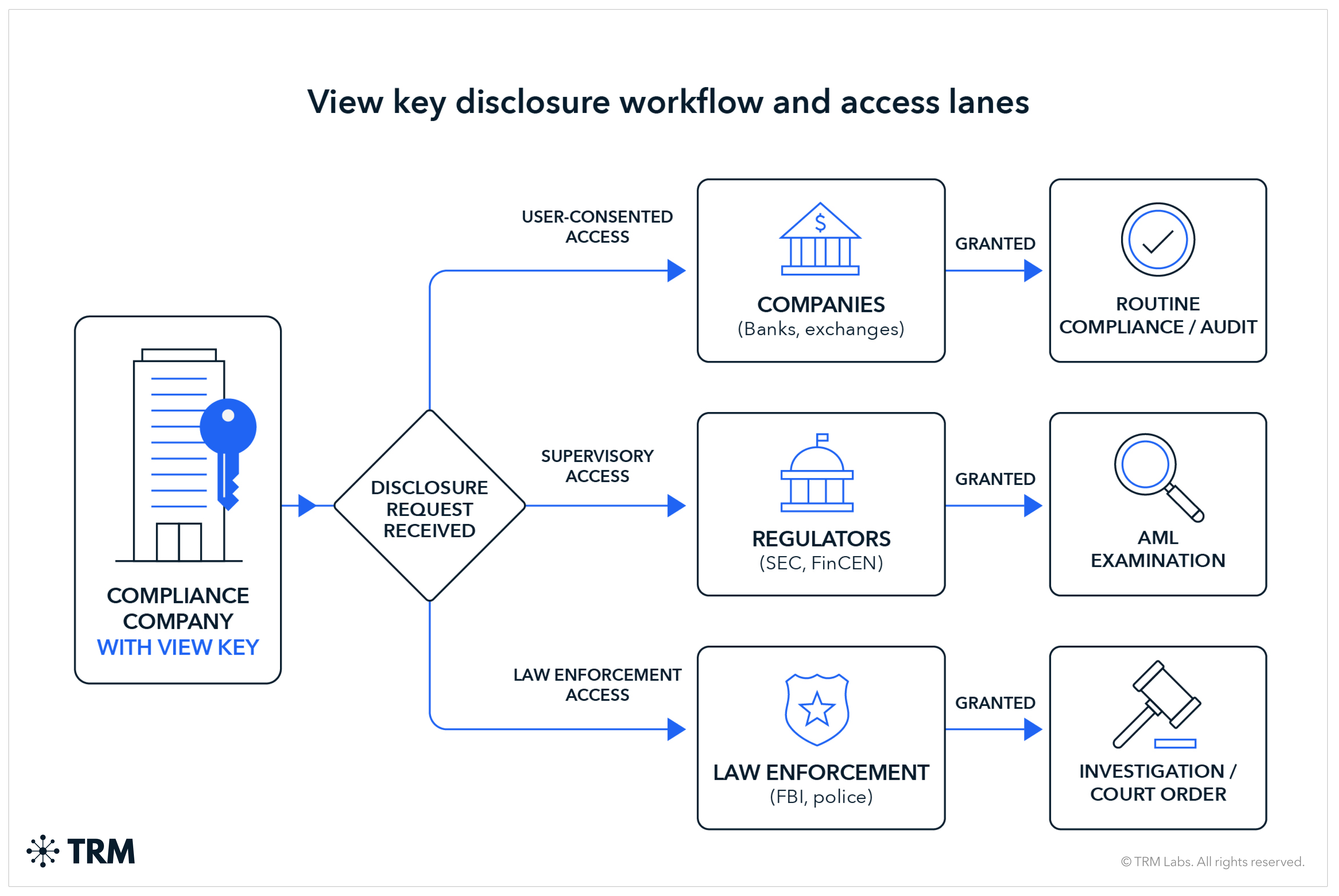

Governing access and due process

Access lanes

Any disclosure regime should define distinct access lanes:

- User-consented disclosure: Routine compliance, audits, transaction counterparties

- Supervisory access: AML program examinations, SAR follow-up, pattern analysis

- Law enforcement access: Court orders, warrants, subpoenas, emergency requests

Access governance framework

For each access lane, policy should define:

Continuity and systemic resilience

Issuer failure scenarios

If an asset issuer goes out of business:

- Who retains the ability to decrypt or produce historical records?

- How are ongoing compliance obligations transferred or wound down?

- What prevents "data hostage" scenarios where critical records become inaccessible?

Provenance and integrity

For disclosed data to be useful in legal proceedings:

- Records must be tamper-evident (cryptographic signatures, append-only logs)

- Chain of custody must be documented

- Authentication of keys and disclosures must be verifiable

Privacy law interactions

On-chain privacy regimes operate within existing privacy law frameworks, creating potential tensions:

- Data minimization: Privacy laws often require collecting only necessary data; broad disclosure mechanisms may conflict

- Retention limits: Requirements to delete data after specified periods may conflict with AML retention requirements

- Cross-border transfers: Disclosing data to foreign regulators or law enforcement may trigger transfer restrictions (GDPR, etc.)

- Right to erasure: Users may have rights to request deletion, but on-chain data is immutable (even if decryption rights can be managed)

These tensions do not have easy answers; they require careful policy design and potentially legislative clarification.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

<span class="premium-content_chapter">PART 7</span>

Hybrid regimes

Where hybrids are necessary

No single privacy regime satisfies all stakeholder needs:

- Transaction view keys provide strong privacy but poor compliance utility

- Address view keys improve investigative capability but create security risks and coverage gaps

- Set membership proofs minimize operational burden and security risk but lack granular investigative utility

- Asset view keys offer strong within-asset compliance but are defeated by cross-asset movement

- Allow-lists provide the strongest compliance but sacrifice permissionless properties

.png)

Likely hybrid configurations:

- Asset-level visibility + conversion constraints: Issuer holds asset view key; users can only convert to other compliant assets. This maintains investigation continuity within a controlled ecosystem.

- Tiered disclosure based on transaction value/risk: Low-value transactions use per-transaction keys; high-value transactions require address-level or issuer-level visibility. Aligns with a risk-based approach.

- Allow-list for institutional + permissionless for retail with enhanced controls: Institutional holders (above threshold) must be allow-listed; retail users can hold with value/velocity limits and time delays.

- Geographic/jurisdictional tiers: Different disclosure requirements based on jurisdiction, reflecting local regulatory requirements.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

<span class="premium-content_chapter">PART 8</span>

Policy recommendations

Recommendations for regulators

1. Define minimum disclosure standards by asset class and transaction type

Not all assets require the same regime. Stablecoins used for payments may warrant different treatment than tokenized securities or privacy-focused cryptocurrencies.

2. Establish clear access governance frameworks

Specify who can request disclosure, under what authority, with what due process, and with what logging and accountability requirements. Ambiguity creates both abuse potential and compliance uncertainty.

3. Require compensating controls proportionate to privacy strength

Assets with stronger default privacy should face stronger compensating controls (KYC requirements, value limits, time delays, conversion constraints). Publish guidance on which control combinations satisfy regulatory expectations.

4. Address cross-asset evasion explicitly

Asset-scoped visibility is defeated if users can freely swap into non-compliant assets. Consider whether conversion constraints or interoperability standards are necessary for certain asset categories.

5. Establish regulatory sandboxes to study and test privacy technologies with hands-on oversight

Within sandbox environments, regulators could offer exemptive relief to innovators who can demonstrate that their alternative tools satisfy the underlying principles of AML/CFT compliance, even if they differ from traditional methods.

6. Coordinate internationally through FATF

Privacy regimes and compensating controls vary across jurisdictions; inconsistency creates arbitrage. Work toward common standards while preserving flexibility for local implementation.

Recommendations for industry (VASPs, fintechs, custodians)

1. Implement standardized key custody and logging

Develop industry standards for how disclosure keys are generated, stored, escrowed, and logged. Interoperability and auditability reduce both compliance burden and security risk.

2. Design for key lifecycle management

Address issuance, rotation, revocation, recovery, and destruction from the start. Retrofitting key management into existing systems is costly and error-prone.

3. Adopt threshold/MPC custody where feasible

Splitting key authority across multiple parties reduces single-point-of-failure risk without eliminating disclosure capability.

4. Document and test continuity plans

What happens if your organization fails, is acquired, or is legally prohibited from operating? Ensure disclosure capabilities and historical records remain accessible.

5. Engage proactively with regulators

The regulatory framework for on-chain privacy is still forming. Industry input on what is technically feasible and operationally practical can shape better outcomes.

Recommendations for protocols and asset issuers

1. Design disclosure mechanisms with governance in mind

Technical capability is not enough — who controls access, under what rules, with what accountability? Build governance into protocol design, not as an afterthought.

2. Minimize breach blast radius

Prefer architectures where compromise of a single key or system does not expose all users. Per-transaction and address-level keys have smaller blast radii than asset-level keys.

3. Consider conversion constraints as a design primitive

If asset-level visibility is the compliance model, restricting conversion to other compliant assets closes the primary evasion vector. This is a significant design choice with market implications, but it may be necessary for certain asset categories. For example, while some DeFi swaps may not be allowed, the conversion restriction does not strictly limit asset composability to the same level as a walled garden or allow-list approach.

4. Plan for issuer failure

Designate backup operators, establish data escrow, and document recovery procedures. Regulatory and legal continuity depends on operational continuity.

5. Be transparent about privacy properties

Users should understand what privacy they have, from whom, and under what circumstances disclosure can occur. Ambiguity creates false expectations and potential liability.

The "nothing to hide" fallacy

A common argument against financial privacy is that legitimate users have "nothing to hide." But this argument fails for several reasons:

Privacy is security

Knowledge of someone's wealth makes them a target. The cryptocurrency community has learned this the hard way through physical attacks, ransomware, SIM swapping, and extortion.

Privacy protects against future threats

Information disclosed today may be used against someone years later, under changed circumstances. Transaction records are permanent — regimes change, relationships end, political climates shift.

Privacy is a baseline expectation

No one argues that bank customers should publish their account balances and transaction histories. The question is not whether financial privacy should exist, but how to provide it in blockchain systems while preserving legitimate investigative capabilities.

The asymmetry of transparency

Public blockchain transparency benefits sophisticated analysts (who can interpret the data) at the expense of ordinary users (who cannot). This is not democratization — it's a transfer of power to those with resources to exploit the data.

Implications for policy design

The user safety case for privacy has direct policy implications:

Default privacy is a consumer protection issue

Regulators concerned with consumer protection should recognize that transparent blockchains expose users to harms that traditional financial systems don't. Privacy-preserving designs with selective disclosure can provide better consumer protection than full transparency.

Privacy and compliance are not opposites

A system can provide strong privacy from public observers while maintaining lawful investigative access through selective disclosure. These are complementary goals, not conflicting ones.

Transparency is not always the "safe" regulatory choice

Regulators sometimes default to transparency requirements on the theory that visibility enables oversight. But transparency also enables criminals to target victims. The optimal policy balances investigative utility against user protection.

"Follow the money" can still work with selective disclosure

Law enforcement doesn't need real-time public visibility to investigate crimes. They need the ability to obtain visibility through legal process when investigating specific cases. Selective disclosure regimes can provide this without exposing all users to public surveillance.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

<span class="premium-content_chapter">PART 9</span>

Conclusion

On-chain privacy and financial compliance are not irreconcilable, but they require deliberate design choices and tradeoffs.

The framework presented here — evaluating privacy regimes against stakeholder needs, assessing residual risks, and scoring compensating controls — provides a basis for informed policy decisions. No single regime is optimal; the appropriate choice depends on asset type, use case, and regulatory context.

What is clear is that the status quo, where privacy-preserving systems exist in regulatory ambiguity, is not sustainable. Regulators will act; the question is whether that action is informed by technical understanding and stakeholder input, or driven by enforcement after the fact.

Industry participants and protocol designers have an opportunity to shape outcomes by engaging constructively with the policy process, implementing reasonable controls, and demonstrating that privacy and compliance can coexist.

The inflection point is here. The choices made now will determine whether on-chain finance develops within a framework that protects users, enables legitimate commerce, and supports effective law enforcement — or whether it fragments into compliant but restrictive walled gardens and non-compliant but unusable alternatives.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

<span class="premium-content_chapter">PART 10</span>

Case studies

The Ronin bridge hack: Testing privacy regimes against a state-sponsored adversary

Background

On March 23, 2022, attackers compromised the Ronin Network bridge — the infrastructure connecting the Axie Infinity game to the Ethereum blockchain — and stole approximately 173,600 ETH and 25.5 million USDC, worth roughly USD 625 million at the time. It remains one of the largest cryptocurrency thefts in history.

The FBI later attributed the attack to the Lazarus Group, a North Korean state-affiliated hacking organization. The theft was not a spontaneous crime of opportunity; it was a sophisticated, planned operation by a well-resourced adversary with experience laundering stolen crypto assets.

The attack and initial fund movement

The attackers gained control of five of the nine validator keys securing the Ronin bridge — enough to authorize withdrawals. The vulnerability arose from a combination of technical architecture (too few validators) and operational security failures (compromised keys).

Once the attackers controlled the bridge, they moved quickly:

Day 1-2: Funds transferred from Ronin bridge to attacker-controlled Ethereum addresses. The theft was not detected immediately; Ronin's team discovered it six days later when a user reported being unable to withdraw funds.

Week 1-2: Attackers began moving ETH through multiple hops across fresh addresses. Some USDC was swapped to ETH via decentralized exchanges.

Week 2-4: Funds began flowing into Tornado Cash, an Ethereum mixing protocol, in tranches designed to avoid patterns. Approximately USD 275 million passed through Tornado Cash in the following months.

Months 2-6: Funds continued to move through mixing services, cross-chain bridges, and eventually toward off-ramps in jurisdictions with weaker AML controls.

What each privacy regime would have revealed

Transparent chain (actual scenario): Because Ethereum is a transparent blockchain, investigators could observe every transaction. Blockchain analytics firms like TRM Labs traced funds in near-real-time. This visibility enabled:

- Identification of attacker addresses

- Tracking of fund flows through mixers

- OFAC sanctions on specific Tornado Cash deposit addresses linked to the attackers

- Eventual recovery of approximately USD 30 million through freezing at centralized exchanges

However, transparency alone did not prevent the theft or enable rapid recovery. The attackers moved faster than interdiction mechanisms could respond.

Which compensating controls could have helped

Key insights

- Speed is the adversary's primary advantage: The attackers moved faster than any human review process could respond. Only automated, real-time controls (delays, limits, smart contract enforcement) can create meaningful friction.

- Transparency enables tracing but not interdiction: Investigators could watch the funds move in real-time, but lacked mechanisms to stop them. Visibility without the ability to act has limited value.

- Asset-scoped controls are defeated by asset swaps: Circle's ability to freeze USDC was useful, but easily circumvented by swapping to ETH. Without ecosystem-wide coordination, asset-level controls are a partial solution.

- Sophisticated adversaries will exploit any gap: Lazarus Group has years of experience laundering stolen crypto. They moved through Tornado Cash before it was sanctioned, exploited cross-chain bridges, and used complex patterns designed to defeat analytics. Controls must assume adversaries will adapt.

- Allow-list models prevent theft but preclude permissionless functionality: The security/permissionless tradeoff is real. For high-value infrastructure like bridges, the answer may be that permissionless models are inappropriate — or that additional controls (delays, limits, insurance) are necessary to manage residual risk.

Outcome

Of the USD 625 million stolen, approximately USD 30 million has been recovered through freezing at centralized exchanges that conducted KYC. An additional amount was frozen in USDC by Circle. The majority of funds were successfully laundered through Tornado Cash and other mechanisms.

In August 2022, OFAC sanctioned Tornado Cash, citing its use by Lazarus Group to launder Ronin and other stolen funds. This action — sanctioning a smart contract rather than a person or entity — was legally contested and later lifted in March 2025, and illustrates the blunt-instrument responses that emerge when more targeted controls are unavailable.

Designing a compliant stablecoin: Balancing privacy, usability, and regulatory expectations

The design challenge

Consider a hypothetical stablecoin issuer — call it "RegularDollar" (RUSD) — seeking to launch a US dollar-backed stablecoin that meets regulatory expectations while preserving reasonable user privacy and market utility.

The issuer faces competing demands:

- Regulators expect the issuer to maintain AML/CFT controls, file SARs on suspicious activity, respond to law enforcement requests, and prevent sanctions evasion.

- Users want privacy from public observers (competitors, criminals who might target wealthy addresses, employers, ex-spouses), low friction for legitimate transactions, and confidence that their data won't be breached or misused.

- Market participants (exchanges, payment processors, DeFi protocols) want clear compliance standards they can implement, interoperability with existing infrastructure, and confidence they won't face enforcement for handling RUSD.

How should RUSD be designed?

Option 1: Fully transparent (status quo model)

RUSD could operate like existing major stablecoins (USDC, USDT) on transparent chains: all transactions visible on the public ledger, issuer maintains blacklist capability, KYC required only at mint/redeem with the issuer.

Strengths:

- Simple to implement

- Full visibility for blockchain analytics

- Issuer can freeze/blacklist addresses

Weaknesses:

- No user privacy from public observers

- Competitive intelligence exposure (treasury positions visible)

- Targeting risk (large holders identifiable)

Compliance assessment: High investigative utility; poor user privacy; relies on exchange-level KYC for identity linkage.

Option 2: Full privacy with per-transaction disclosure

RUSD could be deployed on a privacy-preserving chain with transaction view keys. Transactions are private by default; users generate disclosure keys for specific transactions when required.

Strengths:

- Strong user privacy

- Granular disclosure control

- Lower breach impact (one key = one transaction)

Weaknesses:

- Fragmented visibility for investigators

- Slow to assemble complete picture

- Relies on user cooperation for disclosure

Compliance assessment: Poor investigative utility for complex cases; strong privacy; likely insufficient to meet regulatory expectations.

Option 3: Asset view key with layered controls (recommended hybrid)

RUSD is deployed on a privacy-preserving chain, but the issuer holds an asset view key providing visibility into all RUSD transactions. Layered compensating controls address residual risks.

Layer 1: KYC at on-ramp/off-ramp only

Users can acquire RUSD by:

- Minting directly with the issuer (full KYC required)

- Purchasing on a regulated exchange (exchange KYC applies)

- Receiving peer-to-peer from another user (no additional KYC)

Users can exit RUSD by:

- Redeeming directly with the issuer (full KYC required)

- Selling on a regulated exchange (exchange KYC applies)

- Sending peer-to-peer to another user (no additional KYC)

Rationale: This mirrors the traditional cash model — KYC at the bank, but peer-to-peer transactions don't require identification. It focuses compliance burden on choke points where identity verification is practical.

Layer 2: Tiered volume limits

Rationale: Risk-proportionate controls. Retail users doing small transactions face minimal friction. Large-volume users — who present greater AML risk — face enhanced scrutiny.

Layer 3: Velocity constraints

- Maximum single transaction: USD 50,000 without 1-hour delay

- Maximum daily volume per address: USD 100,000 without enhanced review

- Transactions over USD 500,000: 24-hour delay with automated screening

Rationale: Creates interdiction windows for large or rapid movements without affecting routine use.

Layer 4: Conversion constraints

RUSD can be freely converted to:

- Other stablecoins whose issuers participate in a mutual compliance framework

- Fiat currency via regulated exchanges

RUSD conversion to non-compliant crypto assets (privacy coins, unvetted tokens) is:

- Not blocked at the protocol level (technically difficult)

- Flagged for enhanced monitoring

- May trigger issuer inquiry or account restrictions

Rationale: Reduces cross-asset evasion while preserving some composability. Acknowledges that protocol-level enforcement of conversion constraints is difficult.

Layer 5: Real-time sanctions screening

All transactions are automatically screened against OFAC and other sanctions lists. Transactions involving flagged addresses are:

- Blocked (if destination is sanctioned)

- Flagged for review (if connected to sanctioned addresses within N hops)

Rationale: Automated compliance for clear-cut cases; human review for ambiguous cases.

Layer 6: Issuer monitoring and SAR filing

The issuer's compliance team monitors aggregate patterns:

- Unusual clustering of addresses

- Rapid velocity spikes

- Geographic anomalies (based on IP data from on-ramp/off-ramp)

- Connections to known illicit addresses

Suspicious activity triggers investigation and, where appropriate, SAR filing.

Rationale: Asset view key enables proactive monitoring without requiring user-by-user key requests.

Modeling user journeys

Retail user (Maria)

Maria receives USD 500 in RUSD as payment for freelance work. She holds it for two weeks, then spends USD 300 at an online merchant accepting RUSD and converts USD 200 to her bank account via a regulated exchange.

Experience

No KYC required for peer-to-peer receipt or spending. Exchange KYC applies for the USD 200 off-ramp (already completed when she set up her exchange account). Her transactions are private from public observers. The issuer can see her transactions, but has no reason to investigate routine activity.

Compliance

Entry and exit points are KYC'd. Peer-to-peer activity is visible to issuer but not linked to her identity unless she exceeds volume thresholds.

Business treasury (Acme Corp)

Acme Corp holds USD 5 million in RUSD as working capital. They make vendor payments of USD 50,000 – USD 200,000, receive customer payments, and occasionally convert large amounts to/from fiat.

Experience

Full KYC required given volume tier. Large transactions (over USD 50,000) face a 1-hour delay. Payments are private from competitors (who cannot see Acme's treasury or vendor relationships). Acme provides source-of-funds documentation for the initial large deposit.

Compliance

Acme is fully identified. All transactions visible to issuer. Large movements flagged for automated review. Clear audit trail for regulators.

Illicit actor (X)

X receives USD 2 million in RUSD from a ransomware payment. X attempts to launder through multiple hops and convert to non-compliant assets.

Experience

X can receive peer-to-peer without immediate KYC. But:

- USD 2 million volume immediately triggers enhanced tier requirements

- Velocity constraints delay movement

- Issuer's monitoring (via TRM Labs) detects unusual pattern (large receipt, immediate fragmentation)

- Conversion to non-compliant assets flags the activity

- X cannot off-ramp through regulated exchanges without KYC that would expose identity

Compliance

Issuer files SAR. Funds may be frozen pending investigation. Even if X moves funds to non-compliant assets, the on-chain record shows the conversion path. X faces significant friction at every exit point.

Residual risks and assessment

This hybrid model does not eliminate risk.

What it achieves:

- Privacy from public observers for all users

- Risk-proportionate controls (low friction for small users, high scrutiny for large)

- Issuer visibility enables pattern detection and SAR filing

- Velocity constraints create interdiction windows

- KYC at choke points provides identity linkage for investigations

What it doesn't achieve:

- Complete anonymity (issuer sees all transactions)

- Fully permissionless operation (volume tiers require KYC)

- Perfect interdiction (sophisticated actors can still move funds before delays trigger)

- Cross-asset tracing (once funds leave RUSD ecosystem, visibility ends)

Key vulnerabilities:

- Stolen identity KYC can introduce bad actors at high tiers

- Peer-to-peer activity below thresholds remains pseudonymous

- Coordinated Sybil operations could structure around volume limits

- Issuer is a single point of failure (breach exposes all users)

Conclusion

A compliant stablecoin can be designed, but "compliant" involves tradeoffs. The hybrid model outlined here offers a reasonable balance:

- Users get meaningful privacy from public observers

- Regulators get issuer visibility and investigation capability

- Market participants get clear, implementable rules

- Bad actors face meaningful friction (though not impassable barriers)

No design eliminates risk. The question is whether residual risks are acceptable given the benefits — and whether compensating controls reduce those risks to manageable levels.

Dusting attacks and the user safety case for privacy

What is a dusting attack?

A "dusting attack" exploits the transparency of public blockchains to deanonymize users and link their addresses together.

The mechanics are straightforward:

- Attacker sends tiny amounts ("dust") of cryptocurrency to thousands or millions of addresses. On Bitcoin, this might be a few hundred satoshis (fractions of a cent). On Ethereum, a few wei of ETH.

- Recipients unknowingly consolidate dust with other funds. When a user spends from their wallet, most wallet software automatically combines available inputs — including the dust — into a single transaction.

- Attacker traces the consolidation. By watching the blockchain for transactions that combine the dust with other inputs, the attacker can link multiple addresses to the same user.

- Attacker builds a profile. Over time, the attacker can identify wallet clusters, estimate total holdings, track spending patterns, and potentially link blockchain activity to real-world identity.

Why this matters: Real-world harms

Dusting attacks are not theoretical. They've been documented across multiple chains and have led to tangible harms.

Targeting for theft and extortion

In 2019 and 2020, multiple reports emerged of cryptocurrency holders receiving extortion emails that referenced their exact wallet balances — information that could only have come from blockchain analysis. Victims were threatened with violence or exposure unless they paid ransoms.

In several documented cases, cryptocurrency holders have been physically robbed by criminals who identified them through blockchain analysis. A database maintained by security researcher Jameson Lopp documents over 100 known physical attacks on cryptocurrency holders. Many victims believe they were targeted based on on-chain wealth visibility.

Competitive intelligence

For businesses holding cryptocurrency as treasury assets, public blockchain transparency means competitors, investors, and counterparties can observe:

- Treasury balances and changes over time

- Payment timing and amounts

- Vendor and customer relationships (if addresses are identified)

This creates strategic disadvantages that traditional businesses don't face when using private banking systems.

Personal privacy violations

Blockchain transparency can expose:

- Salary payments (if employer and employee addresses are known)

- Donations to political causes or controversial organizations

- Purchases of legal but sensitive goods or services

- Relationship patterns (recurring payments between addresses)

For individuals in vulnerable situations — domestic abuse survivors, political dissidents, LGBTQ+ individuals in hostile jurisdictions — this exposure can be dangerous.

Case example: The Binance dust campaign

In October 2020, users of Binance and other exchanges reported receiving small amounts of unsolicited cryptocurrency. Analysis revealed a coordinated dusting campaign targeting millions of addresses.

The purpose was unclear — it could have been blockchain analytics research, preparation for phishing campaigns, or testing for a future attack. But the scale demonstrated how cheap and easy dusting has become:

- Sending dust to 1 million addresses might cost a few hundred dollars

- Automated tools can track consolidation patterns

- Commercial blockchain analytics services can then be used to further deanonymize targets

The privacy argument

These harms illustrate why privacy is not merely a preference for criminals — it's a safety feature for legitimate users.

The traditional finance baseline

When someone pays with a credit card or bank transfer, the merchant sees only what's necessary for the transaction. The merchant doesn't see the customer's total bank balance, other purchases, employer, or spending history. Privacy is the default; disclosure is selective and consent-based.

Public ledgers force a trade-off that traditional finance never demanded: to make a payment, one must expose their entire balance sheet and transaction history. This open architecture effectively eliminates the financial confidentiality that institutions and individuals have relied upon for decades.

This is a regression from traditional financial privacy — not an improvement.

How privacy regimes address dusting attacks

Transaction view keys: If transactions are private by default and senders can generate view keys for specific transactions, dusting attacks become ineffective. The attacker can send dust, but they cannot observe whether or how it's consolidated — the recipient's other transactions are invisible.

Address view keys: If addresses are private by default, dust transactions are invisible to the attacker even if the recipient consolidates funds. The attacker would need the recipient's address view key to observe anything.

Asset view keys: Don't directly address dusting, since the issuer (not public attackers) holds visibility. However, users are protected from public observers including dusters.

Allow-list models: Effectively prevent dusting since only approved addresses can transact. The attacker cannot send unsolicited dust.

Balancing user safety with investigative needs

The dusting attack problem illustrates a key point: public transparency is not neutral. It benefits some parties (investigators, analytics firms) while harming others (individual users seeking financial privacy).

A well-designed privacy regime should:

- Protect users from public observers (including criminals, competitors, and stalkers)

- Preserve lawful investigative access (for regulators and law enforcement with proper authorization)

- Provide selective disclosure mechanisms (so users can prove transactions when needed)

This is exactly the architecture that selective disclosure regimes — transaction view keys, address view keys, or asset view keys with appropriate governance — are designed to provide.

Conclusion

Dusting attacks are a symptom of a broader problem: public blockchain transparency treats all observers equally, whether they're law enforcement investigating crimes, analytics firms serving institutional clients, or criminals identifying targets.

Privacy-preserving blockchains with selective disclosure mechanisms offer a better model — one that protects users from public observers while preserving lawful investigative access. This is not a tradeoff between privacy and security. For many users, privacy is security.

Policy frameworks that fail to recognize this will either push users toward fully opaque systems (which genuinely do undermine compliance) or leave users exposed to harms that a better-designed system could prevent.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

<span class="premium-content_chapter">APPENDIX</span>

Glossary

Address view key:

A cryptographic key that provides visibility into all transactions associated with a specific blockchain address. Useful only in systems where the transaction graph exists to analyze.

Allow-list:

A set of pre-approved addresses permitted to hold or transact a particular asset. Provides strong compliance through access control but sacrifices permissionless properties.

Anonymity:

A privacy type where the transaction graph (sender/receiver linkage) is hidden. Amounts may or may not be visible. Fundamentally incompatible with graph analysis.

Association Set Provider (ASP):

An entity that curates a set of "clean" deposit addresses and publishes a cryptographic commitment (Merkle root). Users prove membership in the set to withdraw funds without revealing which specific deposit is theirs. Limitation: Only excludes known bad addresses; fresh addresses pass all checks.

Asset view key:

A cryptographic key held by an asset issuer that provides visibility into all transactions involving that asset. Enables issuer-level compliance monitoring but creates concentration risk.

Compensating control:

A measure implemented to reduce residual risk when a primary control is insufficient. Examples include time delays, volume limits, and KYC requirements.

Confidentiality:

A privacy type where transaction amounts and balances are hidden, but the transaction graph (who transacted with whom) remains visible. Preserves graph analysis capability while providing meaningful privacy.

Curator:

An entity responsible for maintaining inclusion sets (ASP) or exclusion lists (POI). Curator integrity and methodology directly affect the compliance value of set membership proofs.

Fresh address:

A newly generated blockchain address with no transaction history. Fresh addresses have no risk score, are not on any exclusion list, and pass all history-based compliance checks. The primary evasion vector against ASP/POI mechanisms.

Full privacy:

A privacy type where both transaction amounts and the transaction graph are hidden. Provides maximum user privacy but eliminates all investigative capability without disclosure mechanisms.

Graph analysis:

The practice of tracing fund flows across the transaction graph to identify patterns, discover unknown actors, and attribute activity to real-world entities. Only possible when the transaction graph is visible. Core investigative technique for financial crime.

Graph-severing privacy:

Privacy systems (anonymity, full privacy) that cryptographically break the link between transaction inputs and outputs. Eliminates graph analysis capability regardless of compensating controls.

KYC (Know Your Customer):

Identity verification procedures required of financial institutions. Links blockchain addresses to real-world identities at designated touchpoints. Limited by P2P transfers that bypass KYC points and by stolen/synthetic identities.

Proof of Innocence (POI):

A zero-knowledge proof demonstrating that a user's funds do NOT originate from addresses on a specified exclusion list (e.g. sanctioned addresses, known hacks). Limitation: Only excludes known bad addresses; fresh addresses pass all checks.

Pseudonymity:

A privacy type where addresses are unlinkable to real-world identity, but all transactions are publicly visible. The baseline for most public blockchains (Bitcoin, Ethereum).

SAR (Suspicious Activity Report):

A report filed by financial institutions with FinCEN when transactions may involve money laundering or other financial crimes. Investigative value depends on ability to trace funds beyond the reported transaction.

Selective disclosure:

The ability to reveal specific information to authorized parties without revealing all information. The mechanism that enables privacy and compliance to coexist in graph-preserving systems.

Set membership proof:

A zero-knowledge proof demonstrating that an element belongs to (or does not belong to) a specified set, without revealing which element. The cryptographic foundation of ASP and POI mechanisms.

Sybil attack:

An attack where a single actor creates many pseudonymous identities (addresses) to gain disproportionate influence or evade per-address controls. Trivially cheap on public blockchains and defeats most volume/velocity limits.

Travel Rule:

FATF requirement that VASPs exchange originator and beneficiary information for transfers above specified thresholds. Applies only at regulated touchpoints; does not cover P2P transfers.

Virtual asset service provider (VASP):

An entity that provides virtual asset services, including exchanges, custodians, and transfer services. Primary compliance perimeter for blockchain AML/CFT.

View key:

General term for cryptographic keys that enable decryption of private transaction data. Includes transaction view keys, address view keys, and asset view keys, each with different scope and access models.

Waiting period / time delay:

A mandatory delay before transactions settle or funds can be withdrawn. Creates a window for detection and response but can be circumvented by pre-positioning and degrades user experience.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

About TRM Labs

TRM Labs provides blockchain analytics solutions to help law enforcement and national security agencies, financial institutions, and cryptocurrency businesses detect, investigate, and disrupt crypto-related fraud and financial crime. TRM’s blockchain intelligence platform includes solutions to trace the source and destination of funds, identify illicit activity, build cases, and construct an operating picture of threats. TRM is trusted by leading agencies and businesses worldwide who rely on TRM to enable a safer, more secure crypto ecosystem.

TRM is based in San Francisco, CA, and is hiring across engineering, product, sales, and data science. To learn more, visit www.trmlabs.com.

.svg)

.png)