The Maduro Superseding Indictment and Cryptocurrency in Venezuela’s Sanctions-pressured Economy

Key takeaways

- The indictment frames narcotics trafficking as a state-enabled financial enterprise, not a standalone criminal operation. Prosecutors allege that Venezuelan government institutions were used to protect drug trafficking, move cocaine at scale, and shield drug proceeds, reducing risk across the trafficking lifecycle and allowing revenue to be generated and recycled over many years.

- Financial flows are central to the case, but they rely on traditional mechanisms, not cryptocurrency. The indictment focuses on diplomatic cover, state protection, bribery, sham entities, and physical movement of cash or value. While prosecutors describe how proceeds were repatriated and converted into power and protection, they do not allege the use of crypto, stablecoins, or blockchain-based laundering.

- Cryptocurrency matters because of Venezuela’s economic collapse and sanctions pressure, not because it is charged in the indictment. Hyperinflation, banking breakdowns, and sanctions have driven widespread use of stablecoins and peer-to-peer markets, which now function as essential financial infrastructure for civilians and, in limited cases, for state-linked trade.

- The forward-looking risk lies at the intersection of entrenched criminal networks and alternative financial rails. TRM’s analysis shows that trafficking organizations typically adopt new financial tools only after achieving scale and stability. While crypto is not central to the charged conduct here, Venezuela’s parallel financial system creates conditions where digital assets could increasingly be layered onto traditional laundering methods over time.

{{horizontal-line}}

Introduction

Late Friday night and into early Saturday, the United States launched a major military operation in Venezuela that included airstrikes over Caracas and other regions and culminated in the capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores. The strikes caused explosions across the capital, triggered a state of emergency, and led to widespread confusion about the country’s leadership. US President Donald Trump announced that Maduro and Flores were taken into custody and flown out of Venezuela to face legal proceedings.

On Saturday morning, the US Department of Justice, acting through the Southern District of New York, unsealed a superseding indictment charging Maduro, Flores, and other senior regime figures with narco-terrorism conspiracy, cocaine importation conspiracy, and weapons offenses. The indictment alleges that Maduro and his co-defendants abused public office to import tons of cocaine into the United States and to forge alliances with violent drug-trafficking organizations.

According to the charging document, Maduro used his authority to protect and promote illegal activity, including transporting large quantities of cocaine under the protection of Venezuelan law enforcement and facilitating money-laundering operations tied to drug proceeds. The indictment further alleges that narcotics-based corruption enriched regime elites and family members, entrenching Venezuela’s political and military leadership.

These charges add a formal legal dimension to the military operation and mark a dramatic escalation in US–Venezuela relations.

This report first explains, in detail, what the superseding indictment actually alleges about money movement, financial flows, and criminal networks.

It then examines what is known about cryptocurrency in Venezuela, explaining how crypto fits into the country’s broader economic and sanctions environment while clearly distinguishing context from charged conduct.

The superseding indictment: A state-enabled financial enterprise

The superseding indictment does not describe a conventional drug cartel operating alongside the state. Instead, it advances a theory that the Venezuelan government itself was transformed into a protective environment for trafficking and allied criminal organizations. Early in the document, prosecutors state that Venezuela became “a safe haven for drug traffickers operating within and across its borders.” This framing is foundational: it signals that the alleged enterprise depended not on evading the state, but on operating through it.

From a financial perspective, the “safe haven” characterization is critical. A protected environment reduces enforcement risk for both physical drug movement and associated financial flows. It enables repeat transactions, predictable revenue generation, and reinvestment without the normal frictions imposed by law enforcement or financial oversight.

This pattern mirrors how TRM Labs has described cartel operating environments globally, where protection, territorial control, and predictable logistics are key enablers of sustained illicit revenue rather than opportunistic transactions.

The indictment repeatedly emphasizes that this protection was “systematic, sustained, and propagated by top government leadership.” In other words, prosecutors are not alleging isolated corruption or rogue officials; they are alleging institutional capture that suppressed risk across the entire value chain of trafficking and proceeds movement.

Drug flow architecture and the geography of value

The indictment describes how cocaine produced in Colombia was moved into Venezuelan territory, consolidated, and dispatched toward international markets. Prosecutors allege that Venezuela’s geography — bordering cocaine-producing regions and offering access to Caribbean maritime routes — made it an ideal transit hub. Cocaine was allegedly shipped onward via go-fast vessels, fishing boats, container ships, and clandestine air routes, ultimately destined for Central America, Mexico, and the United States.

What distinguishes this account is not merely the routes, but the alleged role of the state in securing them. The indictment asserts that traffickers operated under “the protection of Venezuelan law enforcement at ports, airstrips, and key transit points.” This protection is alleged to have lowered interdiction risk and enabled trafficking at scale.

From a financial standpoint, scale matters. High-volume trafficking implies high-volume proceeds. When operations are protected rather than hidden, revenue generation becomes systemic, not episodic. This sets the stage for durable financial networks capable of absorbing, moving, and redeploying large sums over time.

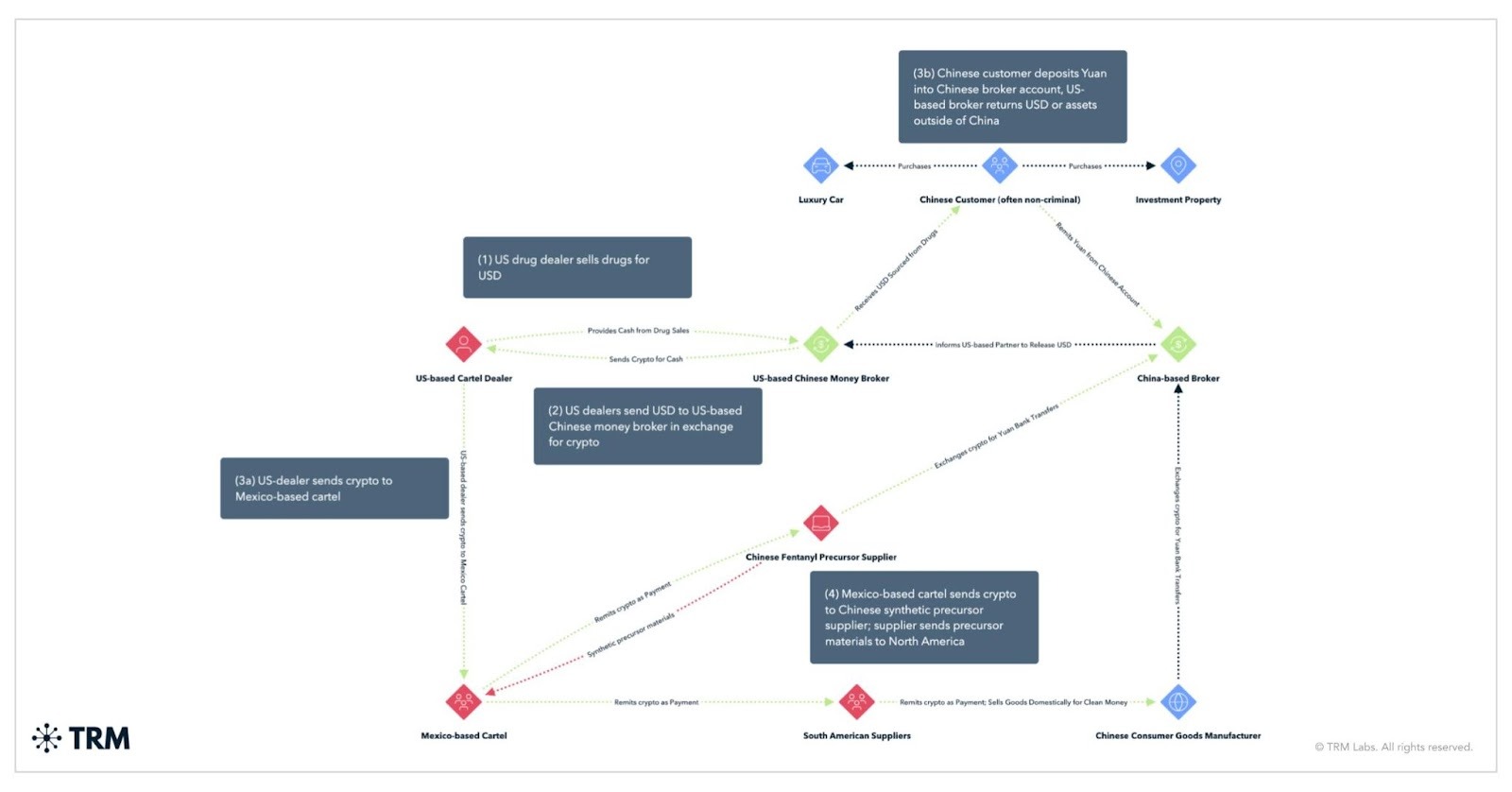

TRM’s analysis of cartel crypto usage emphasizes that cartels typically adopt new financial tools only after achieving this kind of scale and operational stability, reinforcing that financial innovation follows entrenched trafficking networks rather than replacing them.

Money movement and repatriation of drug proceeds

The indictment is particularly revealing in how it describes the movement of drug proceeds. One of the most specific and striking allegations is that Maduro-linked officials used “diplomatic privileges and immunities” to facilitate the movement of money. Prosecutors allege that officials “provided Venezuelan diplomatic passports and diplomatic cover for aircraft used by money launderers to repatriate drug proceeds from Mexico to Venezuela.”

This language matters. It alleges not just concealment, but institutional shielding of financial flows. Diplomatic cover, if abused as alleged, would exempt aircraft and passengers from routine customs inspections and financial scrutiny, allowing large quantities of cash or equivalent value to move with minimal oversight.

In practical terms, this suggests a mechanism for reconcentrating liquidity within secure networks in Venezuela. Drug proceeds generated abroad could allegedly be returned under diplomatic protection, reducing exposure to seizure, reporting requirements, or third-party detection. This is one of the clearest windows the indictment provides into how prosecutors believe value moved, not just where drugs traveled.

TRM has noted in separate cartel-focused research that large-scale trafficking organizations continue to rely heavily on physical cash, trade-based laundering, and state or quasi-state protection for moving core proceeds, with crypto generally playing a secondary or complementary role rather than replacing these mechanisms.

Corruption, bribery, and the circulation of proceeds

The indictment repeatedly alleges that drug profits were used to corrupt and capture Venezuelan institutions. Prosecutors describe proceeds being used to bribe officials, secure loyalty, and maintain protection arrangements. The document states that cocaine trafficking generated “profits that were used to corrupt and capture Venezuelan institutions and law enforcement.”

This is a circular financial model. Drug proceeds are not merely accumulated; they are reinvested into the system that enables trafficking. Money buys protection, protection enables trafficking, trafficking generates more money. This cycle is central to the government’s theory and explains why the alleged enterprise could persist over decades.

The indictment also references the use of false documentation, sham entities, and facilitators to conceal proceeds. While the document does not provide granular detail on specific laundering vehicles, it describes familiar typologies: shell companies, falsified records, and intermediaries who move value under the guise of legitimate activity.

TRM’s cartel research similarly finds that crypto is most often layered on top of these traditional laundering structures, rather than serving as the primary mechanism for proceeds concealment.

Networks and alliances: Cartels, armed Groups, and financial interdependence

A substantial portion of the indictment is devoted to describing alliances with transnational criminal organizations and armed groups, including the FARC and successor entities. Prosecutors portray these relationships as mutually reinforcing. Armed groups gained safe haven, logistical depth, and political shelter. Venezuelan officials allegedly gained revenue streams, enforcement partners, and strategic leverage.

The narco-terrorism charge reflects the government’s view that these alliances elevate the case beyond organized crime. Financial flows are framed not just as criminal profit, but as funding for violence, weapons acquisition, and destabilizing activity. The indictment alleges that narcotics proceeds were used to acquire “military-grade weapons” and to support armed groups allied with the regime.

From a financial perspective, this means proceeds were converted into coercive power. Money funded weapons, weapons enforced routes, routes sustained trafficking, and trafficking generated more money. Financial flows, violence, and political authority are presented as tightly coupled.

Family, patronage, and concentration of wealth

The indictment places significant emphasis on family members and close associates, including Cilia Flores and Maduro’s son. Prosecutors allege that narcotics-based enrichment extended to regime insiders and family, creating a patronage system that bound loyalty to financial benefit.

This concentration of wealth serves a strategic function in the government’s narrative. By embedding proceeds within a trusted inner circle, the alleged enterprise reduced internal risk and increased durability. Financial flows thus supported not only personal enrichment, but regime stability.

Forfeiture and the centrality of financial flows

The superseding indictment is explicitly structured as a proceeds case. It seeks forfeiture of property “constituting or derived from proceeds” of the alleged crimes, as well as property “used or intended to be used” to facilitate them. It also invokes substitute-asset provisions, allowing the government to seek equivalent value if direct proceeds cannot be located.

This signals that prosecutors anticipate proceeds may be hidden, commingled, or converted. It also underscores that the ultimate objective is not only conviction, but dismantling the financial foundation of the alleged enterprise.

Notably, all of this financial discussion is grounded in traditional mechanisms. The indictment describes money movement through diplomatic cover, state protection, intermediaries, and conventional laundering techniques. There is no reference to digital assets of any kind.

Cryptocurrency in Venezuela: Economic collapse and financial adaptation

The superseding indictment contains no references to cryptocurrency. To understand why crypto nonetheless matters, it is necessary to examine Venezuela’s broader economic environment. Over the past decade, hyperinflation, repeated currency devaluations, capital controls, and collapsing oil production devastated the formal financial system. The bolívar became unusable as a store of value. Access to banking deteriorated. Correspondent relationships disappeared as global banks de-risked.

In this vacuum, digital assets — particularly US dollar-denominated stablecoins — emerged as practical financial infrastructure. For many Venezuelans, crypto is not speculative. It is a way to preserve value, receive remittances, pay for goods and services, and access global commerce when banks are unreliable or unavailable.

TRM describes this in a recent report titled, “Understanding Venezuela’s Crypto Landscape Amid Global Tensions,” as the emergence of “dual-use crypto rails,” where the same infrastructure supports everyday civilian economic activity while also resembling alternative payment channels capable of cross-border settlement.

Peer-to-peer markets and informal brokers became central to this system, enabling conversion between cash, bank balances, and digital assets. Over time, these rails became normalized and deeply embedded in daily economic life.

Sanctions pressure and institutional crypto use

US sanctions on Venezuela’s oil sector and state-owned companies severely limited the country’s ability to use the US dollar and the international banking system. Because the Venezuelan government relies heavily on oil exports for revenue, those restrictions created strong pressure to find other ways to get paid and move money across borders.

In that context, public reporting has shown that Venezuela’s state oil sector and related intermediaries began using dollar-denominated stablecoins like USDT for some transactions. In practice, this meant asking buyers to prepay or settle deals using digital dollars rather than traditional bank wires. Stablecoins functioned like cash dollars online, allowing payments to move without passing through banks that might freeze or block sanctioned transactions.

This matters because it explains where cryptocurrency most clearly intersects with the Maduro government. The use of stablecoins appears tied to keeping oil trade and state revenues moving under sanctions, not to the drug-trafficking allegations laid out in the indictment. The narcotics charges focus on cocaine trafficking, protection by state security forces, and the movement of drug proceeds through traditional channels — not on the use of cryptocurrency.

Structural risk in Venezuela’s crypto ecosystem

TRM's analysis of Venezuela's crypto landscape describes a dual-use environment. On one side is widespread legitimate adoption driven by economic survival. On the other is a set of structural features that create sanctions and illicit-finance risk.

High reliance on peer-to-peer trading disperses conversion points. Informal exchanges and nested service providers operate with uneven oversight. Regulatory ambiguity complicates enforcement. These conditions do not make crypto inherently illicit, but they reduce transparency and increase the potential for misuse by sophisticated actors, including criminal organizations that TRM has observed experimenting with crypto primarily for limited functions such as payments, hedging, or short-term value transfer rather than core laundering.

The Petro and the politics of alternative rails

Venezuela’s earlier experiment with the Petro — a government-linked digital token marketed as an oil-backed alternative to traditional finance — provides additional context. While the Petro failed to gain meaningful adoption, it signaled the regime’s willingness to experiment with digital assets as a response to financial isolation.

The failure of the Petro did not end Venezuela’s engagement with crypto. Instead, it shifted activity toward market-driven stablecoin adoption at scale.

Conclusion

The superseding indictment against Nicolás Maduro and his co-defendants alleges a sprawling, state-enabled narcotics enterprise sustained by traditional money movement mechanisms: diplomatic cover, institutional protection, bribery, and reinvestment of proceeds into power and weapons. It provides specific examples of how value allegedly moved and was shielded, but it does not allege the use of cryptocurrency.

Separately, Venezuela’s crypto ecosystem reflects how a sanctioned, collapsing economy adapted by building alternative financial rails. Stablecoins, peer-to-peer markets, and informal brokers became essential infrastructure for ordinary life and, in some cases, for state-linked trade under sanctions pressure.

These two realities intersect not because crypto is charged as a criminal tool in this indictment, but because financial infrastructure matters. As legal proceedings continue and attention turns to assets, proceeds, and networks, understanding both the charged conduct and the contextual financial environment will be essential for policymakers, investigators, and the private sector alike.

{{horizontal-line}}

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

1. Does the superseding indictment allege that Nicolás Maduro or his associates used cryptocurrency to traffic drugs or launder money?

No. The indictment contains no references to cryptocurrency, stablecoins, wallets, exchanges, or blockchain transactions. All alleged money movement and laundering activity relies on traditional mechanisms such as diplomatic cover, state protection, intermediaries, and conventional laundering techniques.

2. If crypto is not in the indictment, why is it discussed in this report?

Crypto is discussed to explain the broader financial environment in which Venezuela operates today. Economic collapse and sanctions have led to widespread use of stablecoins and peer-to-peer markets. This context is important for understanding how value moves in Venezuela, even though it is not part of the charged narcotics conduct.

3. How do cartels typically use cryptocurrency, according to TRM’s research?

TRM’s analysis shows that cartels generally rely on physical cash, trade-based laundering, and trusted intermediaries for core proceeds. Crypto is usually used in limited or complementary ways — such as payments, short-term value transfer, or hedging — rather than as the primary method for laundering large-scale drug profits.

4. What is meant by “dual-use crypto rails” in the Venezuela context?

“Dual-use crypto rails” refers to financial infrastructure that supports legitimate civilian activity — like remittances, savings, and commerce — while also functioning as an alternative payment channel capable of cross-border settlement. The same rails that help households survive economic collapse can, in theory, be misused by sophisticated actors.

5. What should policymakers and investigators focus on going forward?

The key focus should be on financial networks, proceeds, and conversion points — both traditional and digital. While this indictment is grounded in conventional money movement, Venezuela’s evolving financial ecosystem means future cases may involve a mix of state protection, informal finance, and alternative payment rails. Understanding how these systems intersect is critical for sanctions enforcement and illicit finance prevention.