Identifying Crypto Artifacts in the Field | Flip Book

A flip book for frontline law enforcement officers

Introduction

This flip book is an essential guide for frontline law enforcement officers, investigators, and other enforcement personnel responsible for triaging crypto artifacts found in the field. Use it as a rapid reference during inspections and investigations — and as a guide to help you identify, assess, and act on potential crypto-related threats.

Objective

The objective of blockchain triage and tracing is to identify, report, and disrupt illicit virtual currency transactions and the actors conducting them. This flip book provides explanations, techniques, strategies, and resources for triaging cryptocurrency artifacts. Its contents should be considered law enforcement sensitive, but appropriate for all levels of blockchain investigators — from first responders to digital asset subject matter experts.

Keep this flip book in the cruiser, in the digital forensics lab, or any other place where triaging evidence related to cryptocurrency might take place.

{{identifying-crypto-artifacts-in-the-field-contact}}

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

Key terminology

<h3 class="premium-content_subhead">Key terms and definitions to know</h3>

Air gap

A security measure in which a device is physically isolated from any network or internet connection. In cryptocurrency, an air-gapped device (such as a hardware wallet) never directly connects to another device via USB, Bluetooth, or Wi-Fi. Instead, it may use QR codes or SD cards to exchange data, allowing transactions to be signed offline without exposing private keys to online threats.

Attribution

The process of linking specific addresses to real world entities (e.g. bc12345 is an address at Binance, a cryptocurrency exchange).

Bitcoin (BTC)

A decentralized virtual currency with transactions confirmed by open-source network nodes where transactions are recorded in the Bitcoin blockchain. Abbreviated “BTC,” addresses are generally 26–62 alphanumeric, beginning with a 1, 3, or bc1 (e.g. 1BvBMSEYstWetqTFn5Au4m4GFg7xJaNVN2).

Legacy addresses (1, 3) are case-sensitive because they use Base58Check encoding, which distinguishes between uppercase and lowercase characters. Native SegWit and Taproot addresses (bc1q, bc1p) are not case-sensitive, as Bech32 and Bech32m are lowercase-only encodings.

Bitcoin ATM

A self-service kiosk that allows users to buy and/or sell Bitcoin (BTC) and other cryptocurrencies using cash, debit cards, or other payment methods. These ATMs provide a physical access point for cryptocurrency transactions, making it easier for users to convert fiat currency into digital assets. Also known as cryptocurrency kiosks, especially when they support multiple digital currencies.

Blockchain

A decentralized and distributed ledger that records transactions securely across a network of computers. Blockchain technology is designed to be transparent, secure, and resistant to modification, making it ideal for various applications beyond cryptocurrencies alone.

Block explorer

A software tool that enables investigators to sort blockchain data, generally including visually organizing transactions into link-charts or graphs.

Blockchain tracing

The process of tracking and analyzing cryptocurrency transactions to trace the movement of funds across blockchain networks. This process leverages the inherent transparency of blockchain technology to identify patterns, locate assets, and even attribute digital wallets to individuals or entities. Also known as crypto tracing.

Border wallet

A memory-based cryptocurrency wallet that uses a visual grid of seed words and a memorized pattern. This allows a person to reconstruct a crypto wallet from memory without carrying any physical or digital artifacts. It is designed to minimize exposure during border searches and is often used to discreetly transport crypto across international boundaries.

Chain-hopping

The process of moving assets between different blockchains or cryptocurrencies in an effort to obfuscate the control of the assets (e.g. sending known illicit Bitcoin to a bridge in exchange for clean Ether).

Counterparty

The party that is on the opposite side of a transaction (e.g. if “A” sends Bitcoin to “B,” “B” is the counterparty to “A”).

Deterministic wallet

A type of cryptocurrency wallet in which all private keys and addresses are mathematically derived from a single root seed, typically a 12–24 word seed phrase. Using a defined algorithm (such as BIP32/BIP44), this single seed allows the wallet to generate an unlimited number of addresses and private keys in a predictable and recoverable way. As long as the seed is known, the entire wallet structure can be regenerated. All BIP39-compatible wallets (e.g. Ledger, Trezor, MetaMask, Trust Wallet) are deterministic wallets.

Ethereum

A decentralized blockchain platform with smart contract functionality. Ether (ETH) is the native cryptocurrency of Ethereum. In addition to ETH, thousands of ERC-20 tokens, such as USDC or LINK, operate on the Ethereum network. Ethereum also supports Layer 2 networks like Arbitrum and Optimism, which run on top of Ethereum to improve speed and reduce transaction costs.

Ethereum addresses are typically 42-character, hexadecimal, and case-insensitive, always starting with 0x (e.g. 0x71C7656EC7ab88b098defB751B7401B5f6d8976F).

Exposure

A measure of how direct proceeds may have traveled from one address to another. If “A” sent Bitcoin directly to “B,” “B” has direct exposure to “A.” If “A” sent Bitcoin to “B,” and “B” sent Bitcoin to “C,” “C” has indirect exposure to “A” and direct exposure to “B.”

Hardware wallets

Physical devices designed to securely store cryptocurrency private keys offline. Hardware wallets keep signing keys isolated from internet-connected systems, reducing the risk of theft or compromise. Hardware wallets are commonly used to authorize transactions while keeping the private key hidden from the host device.

Know Your Customer (KYC) information

Commonly abbreviated as “KYC.” The real-world identification that an entity may collect in order to do business with an individual.

Mixers and tumblers

Services that obfuscate the origins and association of funds by creating commingled pots of funds which then send proceeds to a destination address, breaking a linear chain of association.

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs)

Unique crypto assets issued on blockchain networks, primarily Ethereum. In the context of assets or currencies, fungibility means that one unit is equivalent to any other unit of the same kind. Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are fungible because one Bitcoin is interchangeable with any other Bitcoin. In contrast, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are unique and not interchangeable. Each NFT has distinct characteristics, identities, and values; this uniqueness is what makes NFTs "non-fungible.”

Seed phrases

A human-readable string, typically 12–24 randomly generated words, that encodes a cryptographic seed used to create a master private key. This master key serves as the root of a deterministic wallet, from which all private keys and public addresses are derived. With just this phrase, wallet software can regenerate access to multiple blockchain wallets.

Software wallets

Software wallets are apps or browser extensions used to store and manage cryptocurrency private keys, generate wallet addresses, and send or receive digital assets. They typically run on smartphones, laptops, or desktop browsers; common examples include MetaMask, Trust Wallet, and Phantom. These wallets may be protected by a PIN, password, biometric unlock, or passphrase, and are often integrated with crypto exchanges, DeFi platforms, and NFT marketplaces.

Token

A virtual currency asset, often associated with a virtual currency that runs on another virtual currency’s blockchain (e.g. an ERC-20 token such as USDT on Ethereum).

Transaction hash

Also known as a “Transaction ID,” this is a unique, alphanumeric sequence associated with a transaction on a blockchain. An investigator can identify specific transactions based on the transaction hash.

Virtual Asset Service Provider (VASP)

A platform used to buy, sell, trade, or exchange virtual currency. Many VASPs (whether centralized or decentralized) may maintain attribution records, which enable investigators to secure real-world attribution of the controller of an address. Though VASPs are located throughout the world and some claim to have no geographic domicile, many VASPs, regardless of physical location, will comply with law enforcement requests for production of records and freezes/seizures. “VASPs” is the nomenclature used by international organizations such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). However, many blockchain investigators use the term “exchanges” synonymously with VASPs — despite VASPs technically including more than just centralized exchanges.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

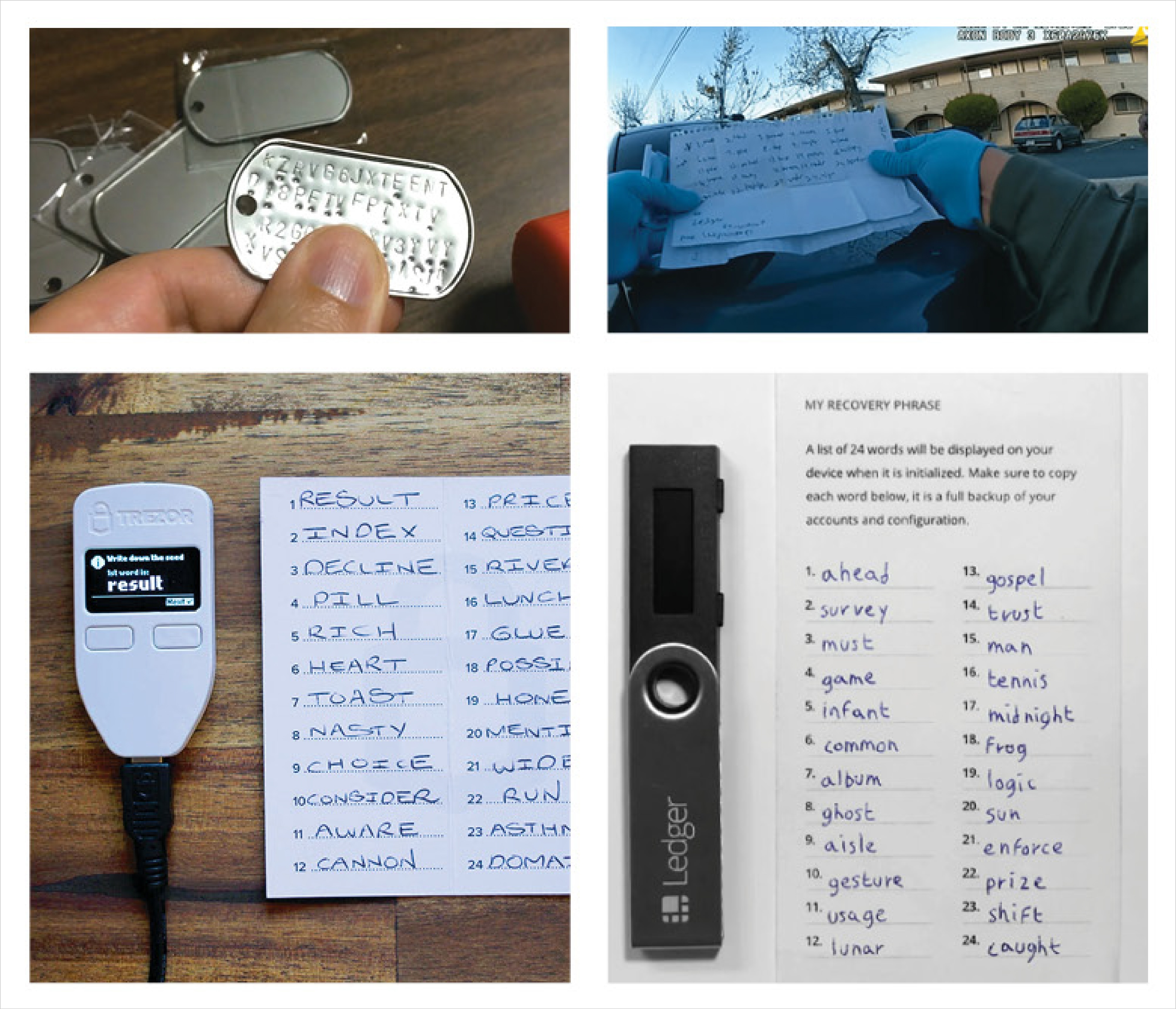

Common crypto artifacts

<h3 class="premium-content_subhead">Common crypto-related objects and their role in investigations</h3>

Hardware wallets

Hardware wallets are physical devices designed to securely store cryptocurrency private keys offline. Unlike older USB-only models, many modern hardware wallets connect via Bluetooth, NFC, or air-gapped QR code scanning — reducing direct USB exposure and enhancing operational security.

These devices isolate private keys from internet-connected systems and require user authentication — typically via a PIN, passphrase, or biometric input. Some include touch screens or physical buttons to approve transactions, and may resemble small remotes, credit cards, or other portable electronic devices.

Why they’re critical in investigations

Hardware wallets are commonly used to securely store and access cryptocurrency holdings. The device itself contains the private keys necessary to authorize transactions, effectively serving as the gateway to the user's digital assets.

While hardware wallets do not store transaction history, connecting them to their companion software can reveal wallet balances and transaction records by querying the blockchain. If a hardware wallet is unlocked or its PIN/passphrase is known, officers may be able to access the associated cryptocurrency.

Hardware wallets can be categorized as either Bitcoin-only or multi-coin devices. Bitcoin-only wallets are designed exclusively for Bitcoin, whereas multi-coin wallets support a variety of cryptocurrencies.

{{identifying-crypto-artifacts-in-the-field-hardware-wallets-callout}}

Where to find them

Due to their compact size and unassuming appearance, hardware wallets can be concealed in various ways. Common locations include pockets, wallets, money belts, bags or purses, electronics bags or pouches, or even shoes. Given these concealment methods, thorough and attentive inspections are essential to identify and secure these devices.

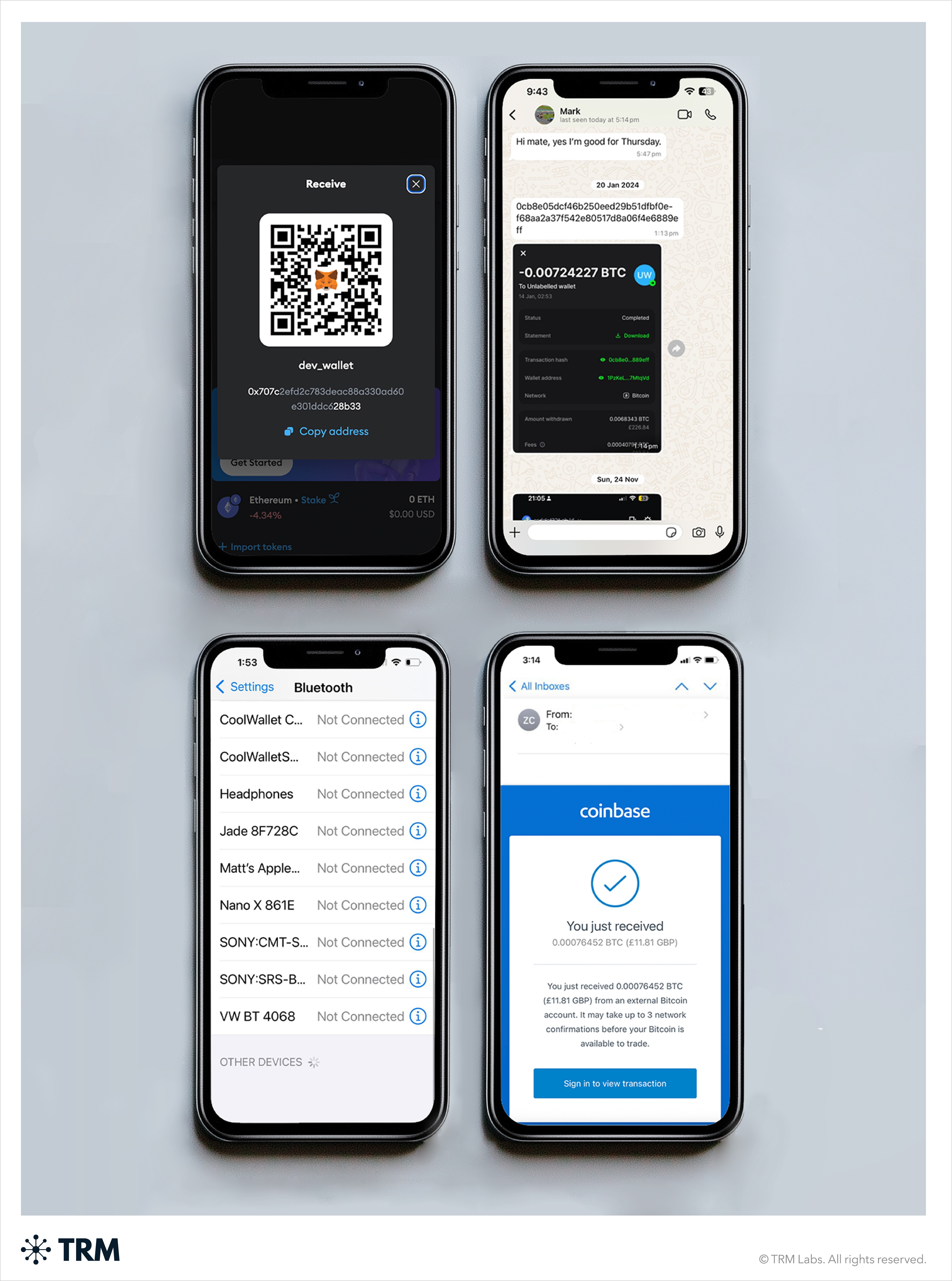

Software wallets

Software wallets are digital applications run on internet-connected devices — including smartphones, laptops, and desktops — that store cryptocurrency private keys locally. These wallets may appear as mobile apps (e.g. Trust Wallet), desktop programs (e.g. Exodus), or browser extensions (e.g. MetaMask, Rabby).

Software wallets are used to quickly access, send, and manage virtual assets from personal devices. These wallets often connect directly to cryptocurrency exchanges or decentralized applications. A single device may host multiple wallets across mobile apps and browser extensions, with each wallet potentially tied to separate accounts, networks, or currencies.

{{identifying-crypto-artifacts-in-the-field-software-wallets-callout}}

Why they’re critical in investigations

The presence of exchange platforms or software wallet apps on a device is a key indicator of active or recent cryptocurrency use, and should immediately prompt deeper questioning.

These apps may signal undeclared digital assets, provide insight into the suspect’s financial behavior, and help assess the sophistication of their crypto activity. If the device is unlocked or the apps are accessible, officers may gain real-time visibility into wallet balances, linked bank accounts, and transaction history. This type of access is high-value: it supports seizure decisions, strengthens evidentiary documentation, and generates actionable intelligence for broader investigations.

Peer-to-peer payment apps like Venmo, PayPal, and CashApp also support various built-in cryptocurrency features, allowing users to buy, sell, and hold assets like Bitcoin and Ethereum directly within the app. Users can send crypto between accounts on the same platform and view balances alongside their fiat holdings — often right on the main dashboard. While these apps are not full crypto wallets and don’t provide private keys or external wallet access, they are commonly used by casual or newer crypto users. Because accounts are linked to real-world identities (via KYC), these apps also offer useful attribution leads.

The presence of both crypto-native apps (e.g. MetaMask) and fiat-to-crypto P2P apps (e.g. CashApp) on the same device may indicate hybrid use — including attempts to off-ramp, launder, or conceal assets. Officers should treat P2P apps as potential crypto indicators and review transaction logs, balances, and linked accounts when accessible.

Where to find them

Software wallets and crypto-related apps may be visible on any screen or within the app drawer of smartphones, but are often hidden in folders, secured with app locks, or stored in private areas (e.g. Secure Folder on Android, App Library on iOS). On laptops, wallets may appear as standalone programs (e.g. Exodus, Atomic Wallet) or as browser extensions (e.g. MetaMask, Rabby). Officers should check browser extension menus, file directories (e.g. Downloads, AppData, Applications), and pinned taskbar apps. Access is commonly protected by passcodes, biometrics, or multi-factor authentication.

Locating software wallets on smartphones

Smartphones may contain multiple versions of wallet apps, hidden instances, or protected folders that do not appear on the home screen. Suspects may use dual apps, secure folders, or cloning tools to conceal crypto usage. Follow the steps below to locate all relevant wallets during device inspections.

Android app drawer and home screen

- Swipe through all home screens to check for visible wallet or exchange apps

- Open the app drawer (swipe up) and scroll for:

- Keywords like “wallet,” “crypto,” “blockchain,” “bitcoin,” or “ethereum”

- Known apps: MetaMask, Trust Wallet, Coinbase, Binance, Phantom, Exodus, Rabby, Atomic Wallet

- Use the app drawer search bar to locate hidden apps

- Look inside folders named Finance, Games, Tools, or Utilities

- Review the recent apps list for signs of quickly closed wallet activity

Detecting dual apps / app cloning

Many Android phones allow users to clone apps for separate accounts. Officers should:

- Navigate to:

Settings → Apps → Dual Apps / App Twin / App Cloner - Review the list of cloned applications

- Open any cloned versions to check for alternate wallets or identities

Samsung Secure Folder

Some Samsung devices offer a private “Secure Folder” with independent credentials:

- Navigate to:

Settings → Biometrics and Security → Secure Folder - Check whether Secure Folder is active

- Review apps and files stored inside

- Attempt lawful access if the device is unlocked

Third-party cloning tools

Third-party apps may enable advanced concealment. Look for:

- Parallel Space

- Island

- Shelter

- Dual Space

- Android “Work Profile” (App Drawer may show tabs for Personal / Work)

iOS app review

Homescreen sweep

- Swipe through each homescreen page, checking for visible icons of known crypto or wallet apps

- Tap into folders often used to organize apps, such as:

- Finance, Utilities, Productivity, Games, or Tools

- Crypto apps may be intentionally miscategorized or hidden here

App Library search

- Swipe left past the last homescreen page to access the App Library

- Use the search bar at the top of the App Library and input:

- Keywords like: “wallet,” “crypto,” “blockchain,” “bitcoin,” or “ethereum”

- Known apps: MetaMask, Trust Wallet, Coinbase, Binance, Phantom, Exodus, Rabby, Atomic Wallet

Settings → app review

- Go to

Settings → General → iPhone Storage - Scroll through the list of installed apps for:

- Unusual or rarely used apps

- Crypto apps with long data usage histories

{{identifying-crypto-artifacts-in-the-field-software-wallets-callout-2}}

Seed phrases and private keys

A seed phrase is a human-readable string, most often 12–24 randomly generated words, used to back up and regenerate a master private key. That master key is then used to derive all associated wallet addresses and private keys within a cryptocurrency wallet.

In some cases, seed phrases may be abbreviated, with only the first four letters of each word written down (e.g. abou aban acce accu instead of about abandon access account). This works because the BIP39 wordlist is designed so that the first four letters of each word are unique, allowing wallet software to reliably auto-complete and validate the full phrase.

Some wallets like Electrum support custom or non-standard seed formats, including short phrases or minimal inputs that don’t follow the typical 12–24 word BIP39 structure.

In practical terms:

- A seed phrase is like a master key; it can unlock the entire vault of addresses and funds

- The master private key is the root of the vault’s lock system

- Each private key is a key to one specific safe or box (individual address)

Why they’re critical in investigations

Possession of a seed phrase enables investigators to recover the entire wallet, including access to potentially hundreds of addresses and associated cryptocurrency funds. Even a single private key may grant access to funds at one address. Both seed phrases and private keys should be treated as high-value evidence and handled in accordance with your agency’s digital asset procedures.

{{identifying-crypto-artifacts-in-the-field-seed-phrases-callout}}

Where to find them

Seed phrases and private keys, which serve as direct access to a suspect’s cryptocurrency, may be stored in both digital and physical formats. Digitally, they are often saved in photo libraries, cloud drives, notes apps, password managers, text messages, or file folders on a suspect’s's electronic device. Wallet passwords may be stored in a password management app (e.g. 1Password, LastPass, or Keeper). And private keys may be in the form of QR codes, because they consist of a long series of letters and numbers, which can be difficult to remember.

Physically, seed phrases and private keys may be written down or printed on small cards resembling credit cards that display the seed phrase, private key, or a QR code representation. These may also appear on notebook pages, hardware wallet backup cards, or scrap paper. Some suspects may store seed phrases in metal crypto safes designed to withstand fire, water, and physical damage, such as the Cryptosteel Capsule or Billfodl.

Common physical hiding places for seed phrases include:

- Inside passport holders, wallets, or document sleeves

- Stored with hardware wallets

- Hidden in notebooks, envelopes, or bag compartments

- Stuck to the back of a phone case or inside a device case

Digital evidence of crypto activity

Digital evidence of crypto activity refers to any content on a suspect’s device that suggests ownership, use, or interaction with cryptocurrency. This evidence may not include a wallet itself, but can reveal key leads for further investigation.

Examples of digital evidence include:

- Wallet addresses (copied in emails, chat threads, or notes)

- Transaction hashes and confirmations (e.g. screenshots, PDFs, or email receipts)

- Cryptocurrency QR codes saved as images

- Screenshots of wallet balances, exchange accounts, or mobile app interfaces

- Photos of seed phrases or private keys

- Chat logs or email threads discussing crypto payments, trading, or scams

- Crypto ATM receipts (physical or photographed)

- Login pages or saved credentials for exchanges, DeFi apps, or NFT platforms

- Mentions of tokens or coins in personal messages, spreadsheets, or documents

- Bluetooth connections to hardware or software wallets

- 2FA accounts associated with crypto

Why it’s critical in investigations

Crypto users often leave behind digital footprints that go beyond just financial transactions — they can reveal intent, coordination, and involvement in criminal activity, offering actionable intelligence at the border. These digital traces may help officers determine whether a person is a victim of a scam attempting to recover lost assets, an unwitting mule or active facilitator moving illicit crypto across borders, or a suspect engaged in broader networks using cryptocurrency to fund or conceal illegal operations.

Where to find it

Digital evidence of cryptocurrency activity is often stored on a phone, laptop, or other personal device. Look for messages, emails, photos, file directories, and chat threads — especially within encrypted apps like Signal, Telegram, or WhatsApp — that may contain screenshots of transactions, wallet addresses, QR codes, or discussions about crypto investments or scams. 2FA apps may also store entries linked to crypto exchanges or wallets, offering additional clues about the suspect’s digital footprint.

In addition, the presence of blockchain-specific messaging apps such as Blockscan Chat or Session can indicate a suspect’s active interest in blockchain technology. These platforms are built on decentralized networks and designed to offer privacy-preserving communication tied to blockchain infrastructure. Critically, Blockscan Chat requires users to have an Ethereum address to send or receive messages — meaning that if the app is installed, the suspect controls a crypto wallet. Session, while not directly tied to a blockchain wallet, is commonly used by privacy advocates and crypto enthusiasts, and may be a red flag for investigators depending on context.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

Introduction to TRM Triage

<h3 class="premium-content_subhead">Triaging crypto evidence using TRM Triage</h3>

Now that you’re familiar with the kinds of crypto artifacts commonly found in the field, let’s take a look at what to do with them.

The goal of any investigation or line of questioning is to identify a suspect’s crypto artifacts and to understand the significance of each piece of crypto evidence (and how it could be used in illicit operations). It’s crucial to know how to handle this evidence appropriately so that it can be leveraged in legal proceedings if necessary.

Let's take a look at the general flow a typical blockchain triage and investigation could take.

Initial screening and risk assessment

Identify high-risk or suspicious actors using intelligence databases, behavioral indicators, and travel history. This is also a good time to ask suspects about recent financial transactions, if they are found with large sums of fiat or digital currencies, and whether they have any crypto holdings (and if so, what the source of those funds is).

Digital evidence identification

Inspect the person’s possessions and/or devices, looking for digital storage devices (e.g. hard drives, USB sticks), hardware wallets (e.g. Trezor wallets), mobile phones, and other crypto artifacts. Inspect installed apps (e.g. MetaMask, Trust Wallet, Coinbase, Binance) on mobile devices, check for suspicious browser extensions or activity in internet history, and review email correspondence or chat messages discussing transactions.

Also keep an eye out for printed or digital QR codes or wallet addresses, or suspicious paperwork containing private keys or mnemonic phrases, as these could be evidence of blockchain transactions and addresses.

Examination of blockchain evidence

TRM Triage is a blockchain intelligence solution that allows frontline officers and investigators — regardless of crypto experience — to triage cryptocurrency evidence found at any point during their investigation. Let’s look at a typical workflow in this tool.

STEP 1: LOCATE EVIDENCE + SEARCH IN TRIAGE

Once you have identified a wallet address or transaction hash, you can use TRM Triage to see if the address has been used to receive or send funds. Your initial search on an active address will uncover relevant blockchains, how many transactions it has been involved in, and the total volume and current portfolio balance in USD. You may also see ownership information, if it has been attributed in TRM.

.jpg)

STEP 2: REVIEW INSIGHTS

After searching the address and selecting the relevant results to your case, you will find several key Insights presented to you. Review these insights for an overview of your address. Expand these insights using the details tab to gain a greater understanding of the addresses activity.

This information can be used to help you consider the following:

- Is the address relevant to your case?

- Is there association to illicit activity/criminality?

- Are there any leads that can be generated?

- Should this address be escalated for further analysis?

As pictured below, TRM Triage enriches blockchain data and identifies next steps to exploit actionable intelligence. For example, an investigator might identify a VASP that can provide account records, highlight exposure of a wallet to high-risk activities, tag and monitor a suspect address for later action, or escalate the intelligence to a specialist to investigate further.

.jpg)

STEP 3: COLLABORATE AND ESCALATE

After triaging the address, you should understand more about its on-chain activity. In order to progress from inspection to investigation, you should now consider how you collaborate with others to determine any nexus between a person’s activities and their crypto activities.

- Escalate to a crypto specialist in your organization for additional support and collaboration.

- Indicate Interest in this address to other users to enable deconfliction and collaboration.

- Contact Investigators who have indicated interest in this address.

- Flag this address as suspicious to notify private sector companies to block this address.

STEP 4: GENERATE LEADS

Depending on your case, you may be able to generate additional leads from the data presented to you in TRM Triage. Use the Contact Exchanges function to reach out to services which may have real world information (PII/KYC) about the owner of this address. In some instances, this information alone is enough to solve a case. You can also expand your victim count by Viewing Victim Reports to see if anyone has reported your address as fraudulent. Uncovering additional victims can help you to further your investigation and may lead to additional seizures and restitution of funds.

STEP 5: MONITOR

Once you’ve reviewed your address’ activity, collaborated where necessary, and generated leads to progress your investigation, you should monitor the address for continued activity — especially if the portfolio balance remains high or has not been used for some time, if ever.

To access TRM Triage or TRM Forensics, reach out to your agency’s TRM admin.

Seizure and evidence documentation

If illicit crypto activity is suspected, law enforcement officers should follow standard procedures for seizure:

- Confiscation and chain of custody:

Digital evidence is copied and logged according to forensic standards, physical wallets and paper records are bagged and secured, and hash values are recorded to ensure data integrity. - Report generation:

Compile reports detailing findings — including wallet addresses, transactions, and connections to illicit activities — along with any forensic analysis summaries and screenshots. - Legal and judicial processing:

The case may be referred to national cybercrime units, financial regulators, or INTERPOL if international money laundering is suspected.

Legal action and asset forfeiture

If cryptocurrency assets are found to be linked to criminal activity, they may be frozen or seized through court orders. The funds might be transferred to government-controlled wallets for asset management, and criminal charges may be filed based on findings.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

Blockchain tracing basics

<h3 class="premium-content_subhead">Getting started with blockchain tracing and cryptocurrency investigations</h3>

The investigative goal of “blockchain tracing,” generally, is to identify the actual controller of an otherwise pseudonymous address. To do so, an investigator may be able to trace blockchain transactions and find counterparty exposure with an entity or individual that can provide the identity of the beneficial controller of an address. More simply, an investigator should follow the money to or from an entity that can provide real-world identity.

.jpg)

While free and open source tools can be used to trace flows of potentially illicit funds, TRM’s Graph Visualizer (pictured above) enriches blockchain data and models transactions in easy-to-build and understand graphs. These features allow investigators to quickly identify exposure to entities that may be able to provide identification data in response to legal process.

One primary strategy for identifying the beneficial controller of an address is to find exposure to a VASP, website, commercial or retail entity, or other third party that may require Know Your Customer (KYC) information to use a platform.

For example, a virtual currency exchange usually requires a customer to provide personally identifying information in order to use the exchange. If an investigator traces the flow of illicit assets to or from an address held at an exchange, the investigator may be able to secure the KYC documents from the exchange in order to identify the beneficial controller of the illicit assets.

A typical blockchain tracing workflow

An investigator’s goal in blockchain tracing is to identify and disrupt illicit activity, following this general workflow:

- Identify illicit conduct

- Trace proceeds

- Seek disruption

- Serve legal process

1. Identify illicit conduct

Identifying illicit conduct begins with locating a suspect’s crypto assets and determining — through intelligence, lines of questioning, and inspection — if they have ties to criminal activity. If illicit conduct is identified, the investigator can use a blockchain tracing tool like TRM to quickly and easily determine the potential scope of the investigation.

Public blockchains record every transaction ever conducted. Therefore, a blockchain tracing tool such as TRM’s Graph Visualizer is able to show graphical representation of associated transactions based upon a simple copy/paste of a single address found during an investigation.

.jpg)

2. Trace proceeds

The most common way an investigator can disrupt the illicit use of virtual currency is by tracing the illicit flow of funds to or from a third party which maintains identifying information or custody of assets.

Here are the typical steps required in blockchain tracing:

- Input transaction hash, incoming/outgoing addresses, or other information into blockchain tracing software such as TRM Graph Visualizer

- Identify any obvious leverage points by mapping out the transaction network

- Identify third parties which may retain information about the controller of the addresses

- Use legal process to obtain information about the controller of the address from the third parties

For more information on blockchain tracing strategies or how to leverage TRM Forensics to follow the flow of funds, check out our available courses on TRM Academy or contact your TRM account manager.

3. Seek disruption

An investigator’s goal is to identify and prosecute the subject conducting the illicit activity, and seize proceeds and/or facilities associated with the illicit activity.

Where an illicit activity has occurred and proceeds of that activity are transferred via cryptocurrency, there are potential violations of law with each transaction. Where an investigator identifies an illicit crypto address associated with the activity (e.g. a facially anonymous online scam), the investigator traces the proceeds of the online scam in order to identify the perpetrators. Once the alleged perpetrator has been identified, the investigator could consider pursuing charges for:

- Money laundering

- Customs fraud or smuggling

- Drug trafficking

- Arms trafficking

- Terrorism / terrorism financing

- Human trafficking

- Violent crimes

- Child Sexual Abuse Material (CSAM)

- Illegal wildlife trade

- Export controls violations

- Sanctions evasion

Each court of competent jurisdiction, worldwide, will have varying criminal statutes and elements to prove for each statute.

4. Serve legal process

Investigators can identify and prosecute individuals for illicit activity by identifying the controller of an address that received proceeds of the illicit activity. Though there are many exceptions (such as where an account was opened with a stolen identity, by a straw person, or by a third party money launderer or money mule), an investigator can frequently identify the controller of an address by issuing a subpoena to a third party which hosts an address that received illicit proceeds.

For more information and best practices for cooperating with other law enforcement agencies to carry out successful blockchain investigations, check out our available courses on TRM Academy or contact your TRM account manager.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

About TRM Labs

TRM Labs provides blockchain analytics solutions to help law enforcement and national security agencies, financial institutions, and cryptocurrency businesses detect, investigate, and disrupt crypto-related fraud and financial crime. TRM’s blockchain intelligence platform includes solutions to trace the source and destination of funds, identify illicit activity, build cases, and construct an operating picture of threats. TRM is trusted by leading agencies and businesses worldwide who rely on TRM to enable a safer, more secure crypto ecosystem. TRM is based in San Francisco, CA, and is hiring across engineering, product, sales, and data science. To learn more, visit www.trmlabs.com.

.svg)

.png)