Investigating Crypto Scams | Flip Book

A flip book for law enforcement teams on the frontlines of disrupting scams

Introduction

<h3 class="premium-content_subhead">The crypto-enabled scam landscape</h3>

According to TRM research, since 2023, at least USD 53 billion in cryptocurrency was sent to fraud-related addresses — a figure that is likely still underreported. Over the past few years, we’ve seen thousands of new investment scam and phishing websites being deployed each month, and received thousands of reports from Chainabuse, the largest publicly available reporting platform for illicit crypto activity. Fraud figures are also likely to rise over time as more instances are found, due to delayed fraud reporting by victims.

Objective

The investigative goal of “blockchain forensics,” (also known as blockchain tracing or blockchain investigation), is to identify the actual controller of an otherwise pseudonymous address. To do so, an investigator may be able to trace blockchain transactions and find counterparty exposure with an entity or individual that can provide the identity of the beneficial controller of an address. More simply, an investigator should follow the money to or from an entity that can provide real-world identity.

This flip book is an essential resource for investigators, police officers, and other law enforcement professionals responsible for investigating cryptocurrency-related scams and fraud. While many of the schemes may look familiar to those well-versed in traditional scams and hacks, scammers’ use of cryptocurrencies to carry out these crimes presents new complexities for investigators who may be new to the blockchain space.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

Key terminology

<h3 class="premium-content_subhead">Key terms and definitions to know</h3>

Address

A unique string of letters and numbers that represents a source or destination of a transaction on a blockchain. Cryptocurrency addresses can be thought of as similar to bank account numbers, as they can be shared publicly to receive funds.

Attribution

The process of linking specific addresses to real-world entities (e.g. bc12345 is an address at Binance, a cryptocurrency exchange).

Bitcoin (BTC)

A decentralized virtual currency with transactions confirmed by open-source network nodes where transactions are recorded in the Bitcoin blockchain. Abbreviated “BTC,” addresses are generally 26–62 alphanumeric, beginning with a 1, 3, or bc1 (e.g. 1BvBMSEYstWetqTFn5Au4m4GFg7xJaNVN2).

Legacy addresses (1, 3) are case-sensitive because they use Base58Check encoding, which distinguishes between uppercase and lowercase characters. Native SegWit and Taproot addresses (bc1q, bc1p) are not case-sensitive, as Bech32 and Bech32m are lowercase-only encodings.

Bitcoin/crypto(currency) ATM

The most common cash-to-crypto service. A self-service kiosk that allows users to buy and/or sell Bitcoin (BTC) and other cryptocurrencies using cash, debit cards, or other payment methods. These ATMs provide a physical access point for cryptocurrency transactions, making it easier for users to convert fiat currency into digital assets. Also known as cryptocurrency kiosks, especially when they support multiple digital currencies. Crypto ATMs can be found in money service businesses, casinos, gas stations, or any other business where one may find a traditional ATM.

Blockchain

A decentralized and distributed ledger that records transactions securely across a network of computers. Blockchain technology is designed to be transparent, secure, and resistant to modification, making it ideal for various applications beyond cryptocurrencies alone.

Block(chain) explorer

A web-based tool or application that allows users to explore and navigate a public blockchain network, sometimes with a graphing and linking function, like TRM Labs’ Graph Visualizer. Its primary function is to provide users with a user-friendly interface to view and search for information about transactions, addresses, blocks, and other data stored on the blockchain.

Blockchain tracing

The process of tracking and analyzing cryptocurrency transactions to trace the movement of funds across blockchain networks. This process leverages the inherent transparency of blockchain technology to identify patterns, locate assets, and even attribute digital wallets to individuals or entities. Also known as crypto tracing.

Chain-hopping

The process of moving assets between different blockchains or cryptocurrencies in an effort to obfuscate the control of the assets (e.g. sending known illicit Bitcoin to a bridge in exchange for clean Ether).

Counterparty

The party that is on the opposite side of a transaction (e.g. if “A” sends Bitcoin to “B,” “B” is the counterparty to “A”).

Cryptocurrency

A digital, encrypted, and decentralized medium of exchange. Unlike the US dollar or the euro, there is usually no central authority that manages and maintains the value of a cryptocurrency. Instead, these tasks are broadly distributed among its users via the internet. Some cryptocurrencies, like “stablecoins,” do have a centralized authority confirming transactions.

Ethereum

A decentralized blockchain platform with smart contract functionality. Ether (ETH) is the native cryptocurrency of Ethereum. In addition to ETH, thousands of ERC-20 tokens, such as USDC or LINK, operate on the Ethereum network. Ethereum also supports Layer 2 networks like Arbitrum and Optimism, which run on top of Ethereum to improve speed and reduce transaction costs. Ethereum addresses are typically 42-character, hexadecimal, and case-insensitive, always starting with 0x (e.g. 0x71C7656EC7ab88b098defB751B7401B5f6d8976F).

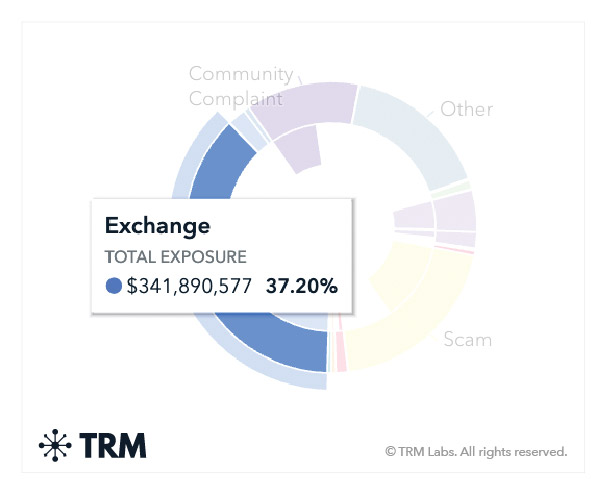

Exposure

A measure of how direct proceeds may have traveled from one address to another. If “A” sent Bitcoin directly to “B,” “B” has direct exposure to “A.” If “A” sent Bitcoin to “B,” and “B” sent Bitcoin to “C,” “C” has indirect exposure to “A” and direct exposure to “B.”

Hardware wallets

Physical devices designed to securely store cryptocurrency private keys offline. Hardware wallets keep signing keys isolated from internet-connected systems, reducing the risk of theft or compromise. Hardware wallets are commonly used to authorize transactions while keeping the private key hidden from the host device.

Know Your Customer (KYC) information

Commonly abbreviated as “KYC.” The real-world identification that an entity may collect in order to do business with an individual.

Liquidity mining

A process where individuals contribute their cryptocurrency to decentralized platforms or protocols to earn assets as rewards. Similar to getting interest by depositing your cash at a bank for the bank to use.

Mixers and tumblers

Services that obfuscate the origins and association of funds by creating commingled pots of funds which then send proceeds to a destination address, breaking a linear chain of association.

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs)

Unique crypto assets issued on blockchain networks, primarily Ethereum. In the context of assets or currencies, fungibility means that one unit is equivalent to any other unit of the same kind. Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are fungible because one Bitcoin is interchangeable with any other Bitcoin. In contrast, non-fungible tokens (NFTs) are unique and not interchangeable. Each NFT has distinct characteristics, identities, and values; this uniqueness is what makes NFTs "non-fungible.”

Private key

A unique, encrypted alphanumeric sequence that serves as the digital equivalent of a physical key to unlock and control digital assets. Having control of a private key allows the controller to manage or transfer the asset.

Seed phrase

A human-readable string, typically 12–24 randomly generated words, that encodes a cryptographic seed used to create a master private key. This master key serves as the root of a deterministic wallet, from which all private keys and public addresses are derived. With just this phrase, wallet software can regenerate access to multiple blockchain wallets.

Smart contract

A self-executing agreement or program written in code that is stored and executed on a blockchain (not dissimilar to an automatic futures contract). It enables parties to interact and conduct transactions in a transparent, automated, and secure manner without the need for intermediaries.

Software wallets

Apps or browser extensions used to store and manage cryptocurrency private keys, generate wallet addresses, and send or receive digital assets. They typically run on smartphones, laptops, or desktop browsers; common examples include MetaMask, Trust Wallet, and Phantom. These wallets may be protected by a PIN, password, biometric unlock, or passphrase, and are often integrated with crypto exchanges, DeFi platforms, and NFT marketplaces.

Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) / Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs)

Government-mandated reports of potentially illicit or suspicious activities to regulatory authorities. SARs/STRs are a vital tool in combating money laundering, terrorist financing, fraud, and other financial crimes.

Token

A virtual currency asset that often runs on another virtual currency’s blockchain (e.g. an ERC-20 token such as USDT on Ethereum). Also sometimes called a “coin.”

Transaction hash

Also known as a “Transaction ID,” this is a unique, alphanumeric sequence associated with a transaction on a blockchain. An investigator can identify specific transactions based on the transaction hash.

Virtual Asset Service Provider (VASP)

A platform used to buy, sell, trade, or exchange virtual currency. Many VASPs (whether centralized or decentralized) may maintain attribution records, which enable investigators to secure real-world attribution of the controller of an address. Though VASPs are located throughout the world and some claim to have no geographic domicile, many VASPs, regardless of physical location, will comply with law enforcement requests for production of records and freezes/seizures. “VASPs” is the nomenclature used by international organizations such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). However, many blockchain investigators use the term “exchanges” synonymously with VASPs — despite VASPs technically including more than just centralized exchanges.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

Scam types

<h3 class="premium-content_subhead">Common crypto-enabled scam typologies</h3>

A crypto scam is any deceptive scheme that exploits cryptocurrency users, investors, or businesses, often for financial gain. These scams can take many forms, from phishing attacks and Ponzi schemes to fake investment platforms and malicious hacking — exploiting the decentralized and often anonymous nature of blockchain technology to deceive victims.

In this chapter, we’ll take a closer look at 14 common types of scams criminals are executing today and what they look like on-chain.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">1. Romance scams</h3>

Romance scams occur when a criminal adopts a fake online persona to gain a victim’s affection and trust, then uses the relationship to manipulate and/or steal from the victim.

Many of these scammers first make contact on dating and social media sites, but quickly request that victims communicate directly on encrypted communication platforms such as WhatsApp or AWS Wickr. Romance scammers make fraudulent promises of future romantic relationships — sometimes even marriage — in order to induce victims into providing them with money, often in the form of virtual currency.

Oftentimes, romance scammers claim to be located in remote locations with substandard internet in order to avoid engaging with their victims face-to-face or over video. This also offers the scammers a chance to deploy a common pretext for needing money from the victim: the scammer is either unable to access his/her bank account or needs money to help them out of an emergency situation.

What do romance scams look like on-chain?

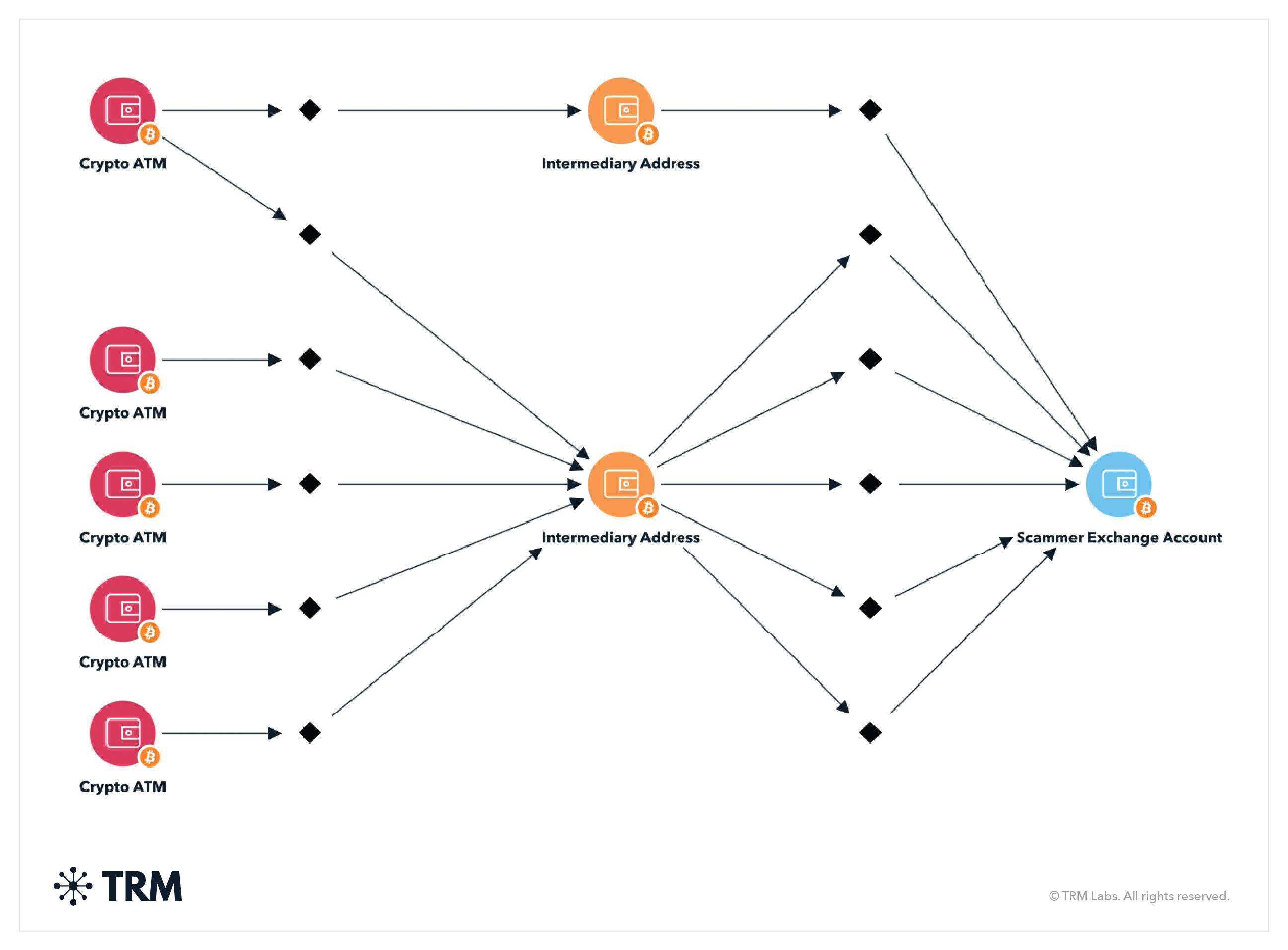

On-chain, romance scams typically show many incoming transactions, originating directly or indirectly from custodial VASPs or ATMs into aggregation addresses, which quickly cash out funds — as seen in the TRM graph below.

While they tend not to have a particularly unique blockchain footprint, here are a few other common hallmarks of romance scams on-chain:

- Scammers may direct multiple victims to send funds to the same set of addresses

- Victims are often directed to crypto ATMs or other easy to use services to send funds

- There is typically little laundering, and tracing is often very simple. Oftentimes, funds go straight to an exchange in one or two hops, as shown in the example above.

- Partially due to the quick paths to an exchange, it can be difficult to link many different individual romance scams together to find romance scam networks with blockchain data alone

- Individual scammer addresses may be active for multiple years and receive spikes of transfers

- This is not true of “pig butchering scams,” which often combine romance and investment scam components, and exhibit different on-chain activity (see more below)

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">2. Pig butchering scams</h3>

The term “pig butchering” is used to describe a common type of romance scam whereby scammers “fatten up” their victims by obtaining increasingly more money from them prior to abruptly ending communication and stealing all of their money.

Also known by the phrase “Shā Zhū Pán” (in reference to their apparent origins in Southeast Asia), these crypto scams rely on psychological manipulation to induce victims to trust their scammers — even when it seems unlikely that what the victim is being told is actually true, or when their claims are too good to be true.

A pig butchering scam occurs when a scammer builds a relationship with their victim over time, then convinces them to invest in fraudulent or fictitious projects. The scammer tries to drain as much money out of the victim as possible, often using fake investment sites that advertise large false profits and/or social engineering techniques, such as intimidation via claims of owing taxes.

There are several common tactics scammers use in these types of scams, including:

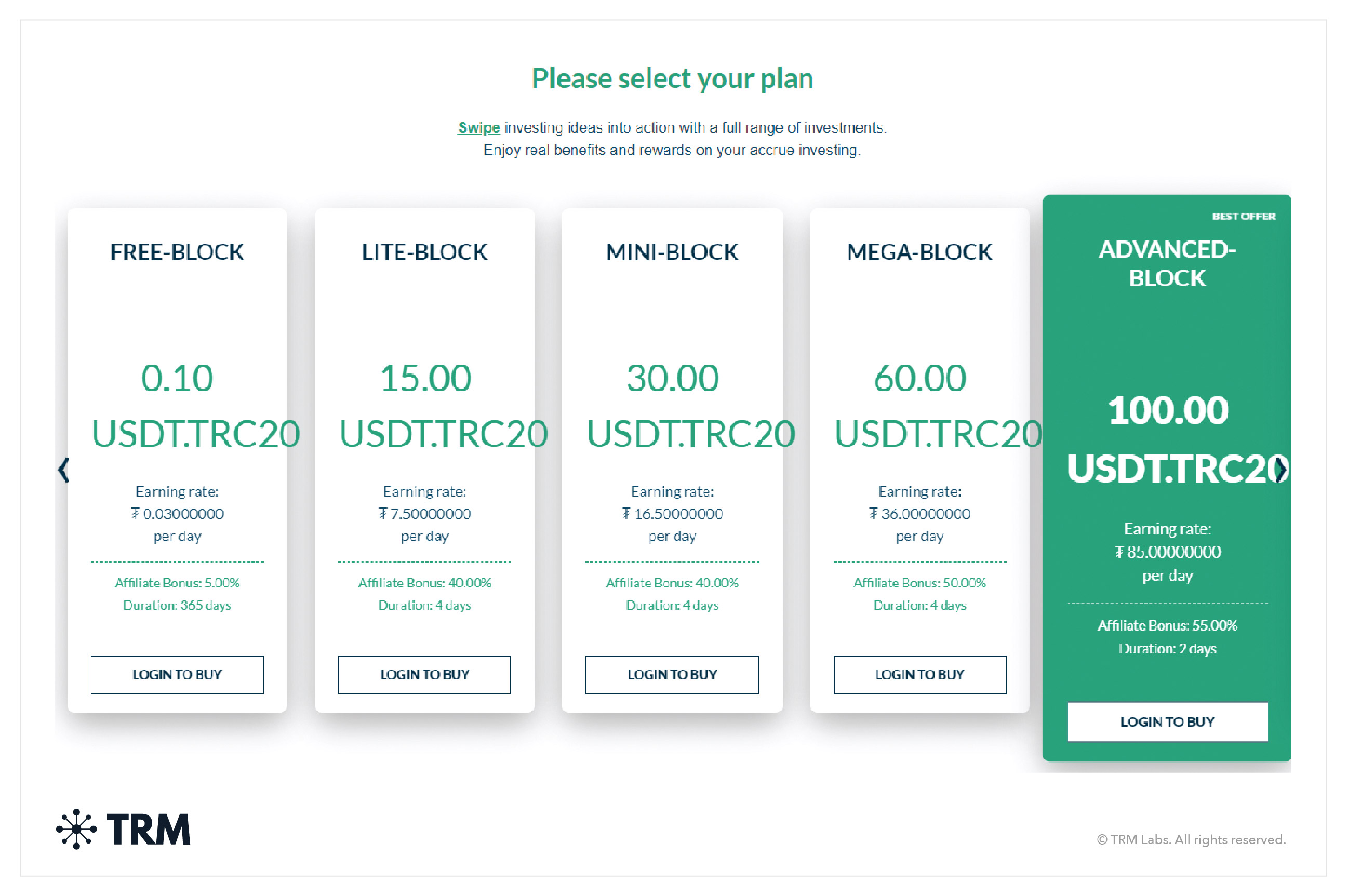

{{investigating-crypto-scams-broker-platform-investment-scams-dropdown}}

{{investigating-crypto-scams-wrong-number-texts-dropdown}}

{{investigating-crypto-scams-liquidity-mining-scams-dropdown}}

{{investigating-crypto-scams-authority-extortion-scams-dropdown}}

What do pig butchering scams look like on-chain?

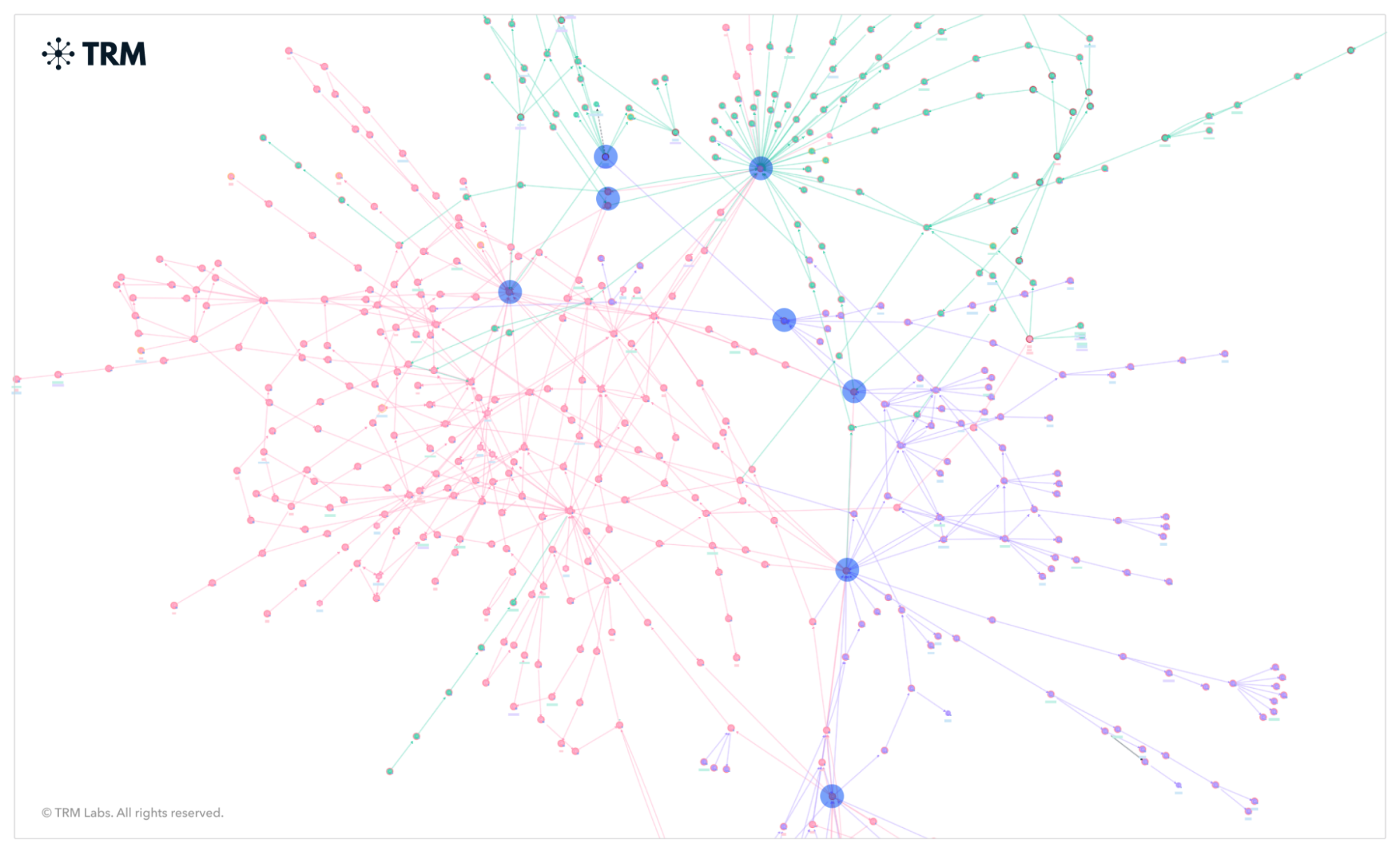

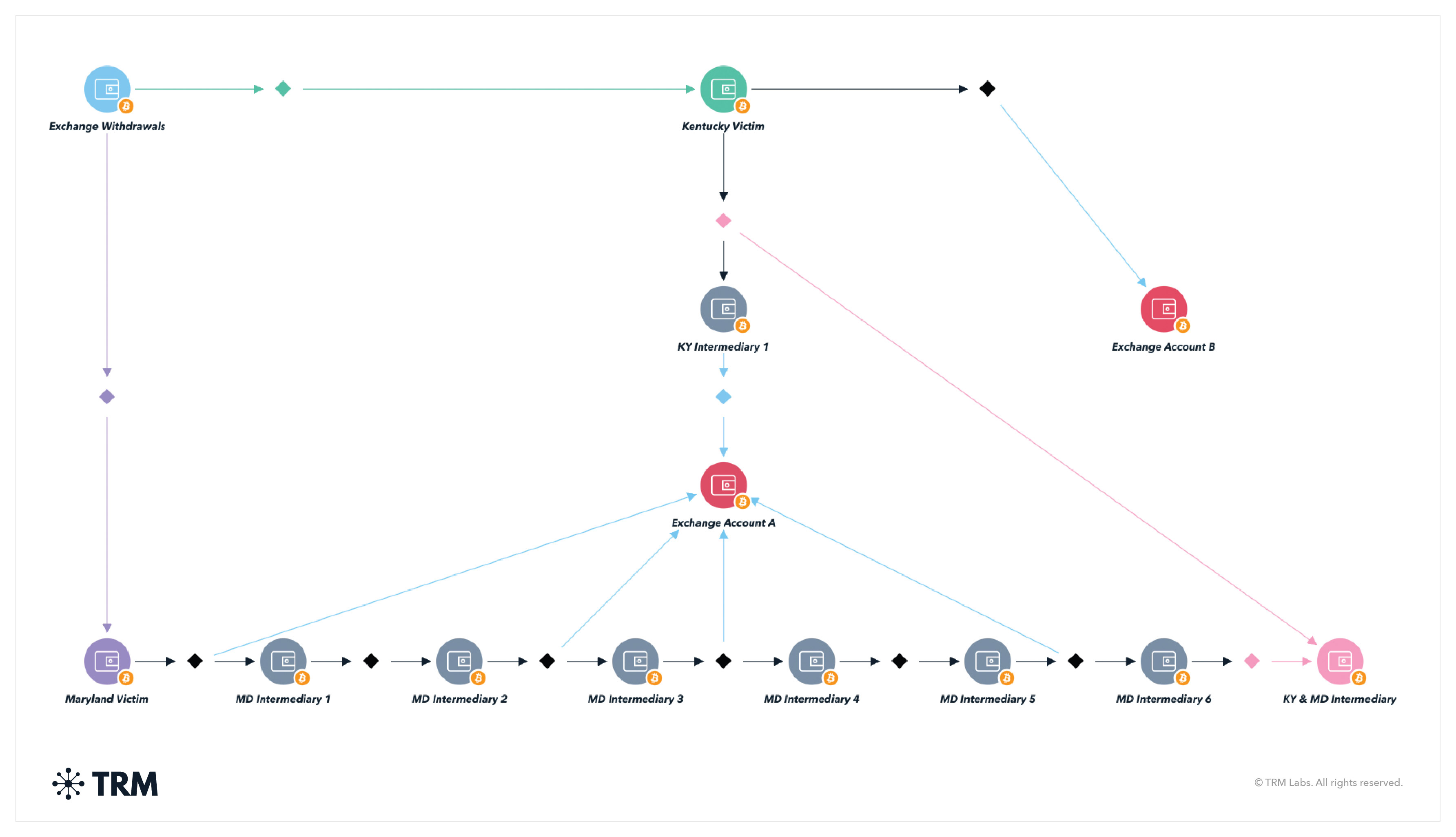

On-chain, pig butchering proceeds often get converted into other currencies at decentralized exchanges. The funds typically enter what appear to be complicated money laundering networks that link multiple pig butchering schemes (as seen in the image below). These funds are sometimes swapped into currencies on other blockchains (often TRON) and/or converted into fiat currency via centralized exchanges, which is where law enforcement teams can often find the best leverage points.

According to TRM, pig butchering schemes are often conducted by professional criminal organizations, sometimes using human-trafficked persons to conduct the scams.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">3. Fictitious projects and fraudulent ICOs</h3>

In this scenario, a scammer pretends to be building a project and solicits investments from victims.

For example, scammers might fake Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) or fundraising events where new cryptocurrencies or tokens are offered to investors in exchange for established cryptocurrencies or fiat currency. These scammers often create real or perceived hype surrounding the launch using marketing and/or false representations to the public. Once the scammers have collected funds from victims, they disappear — referred to as a “rug pull” or “exit scam.”

What do fraudulent ICOs look like on-chain?

Identifying a fraudulent project can be challenging based solely on its blockchain footprint, particularly before a scammer executes an exit scam. However, there are specific characteristics that may point to manipulation and fraudulent activities.

One clear indicator is “wash trading,” where the same entity buys and sells a token back and forth to artificially inflate its trading volume or perceived value. This creates the illusion of liquidity and demand, which can mislead investors into thinking the asset is legitimate or profitable. Other signs include suspicious token distribution patterns (such as a significant portion of tokens being held by a small number of wallets) and unrealistic price movements (where a token sees sudden, unexplained price increases followed by sharp drops) often linked to exit scams. Additionally, the lack of transparency around the project's development, team members, or technical whitepapers can be a red flag, as legitimate projects typically provide clear documentation and regular updates.

Investigators should research the off-chain properties of these projects to help determine their legitimacy, including any potential filings with regulatory authorities.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">4. Rug pulls and exit scams</h3>

Rug pulls and exit scams are fraudulent schemes where the creators or developers of a crypto project intentionally abandon the project or manipulate its functionalities to steal investors' funds. Scammers typically deceive investors by initially presenting a seemingly legitimate and promising project, then abruptly exiting it with the funds invested by unsuspecting participants. Some rug pulls are complex investment vehicles, while others are framed as exchanges, vendors on marketplaces, or unlicensed money service businesses.

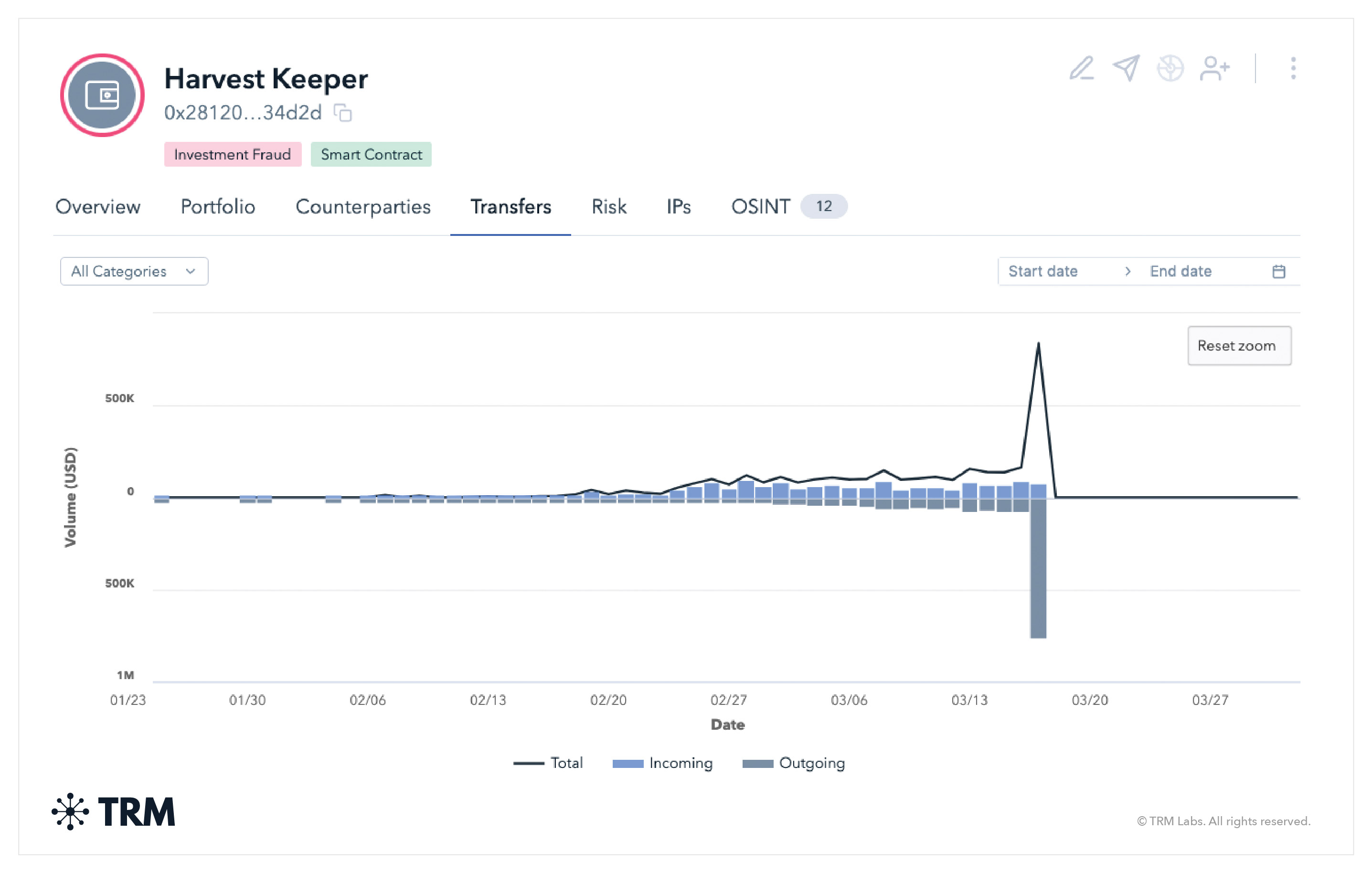

What do rug pulls and exit scams look like on-chain?

Exit scams can happen slowly over time — though the creators of a project typically tend to withdraw as many funds as they can in one go. Their transfer activity often resembles the graphic from TRM below, where the large outgoing spike represents the exit scam. Funds are often pulled out of a smart contract or liquidity pool associated with the project.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">5. Ponzi and pyramid schemes</h3>

A Ponzi scheme is a type of investment fraud where returns to existing investors are paid using the contributions of new investors, rather than from legitimate profit.

These schemes often pay out the promised returns to the initial investors during the early stages of the scam in order to induce additional investment. And to sustain the scheme, the operator focuses on recruiting new investors — through word-of-mouth referrals, social media marketing, or hosting seminars and events to target potential victims — leveraging the promise of high returns and the “success stories” of early investors to entice new participants to join.

Instead of investing the funds in legitimate ventures as promised, Ponzi scheme operators divert the majority of the incoming investments for personal use or to pay off their earlier investors. Only a small portion of the funds may be used for actual investments or operations to maintain the illusion of a legitimate business.

Because Ponzi schemes rely solely on recruiting new investors to sustain itself, they do not generate legitimate revenue from investments — so a flow of new funds is essential to meet the withdrawal requests of existing investors and to maintain the appearance of a successful venture. Once new investment slows down or hits a saturation point, the scheme collapses and most investors are left with significant losses.

Pyramid schemes are closely related to Ponzi schemes. A pyramid scheme is a fraud that recruits members with a promise of payments for enrolling others into the scheme, rather than supplying any real product or service. Many Ponzi schemes rely on Pyramid-scheme-like elements to entice investors with strong incentives for recruiting as many new investors as possible.

What do Ponzi and pyramid schemes look like on-chain?

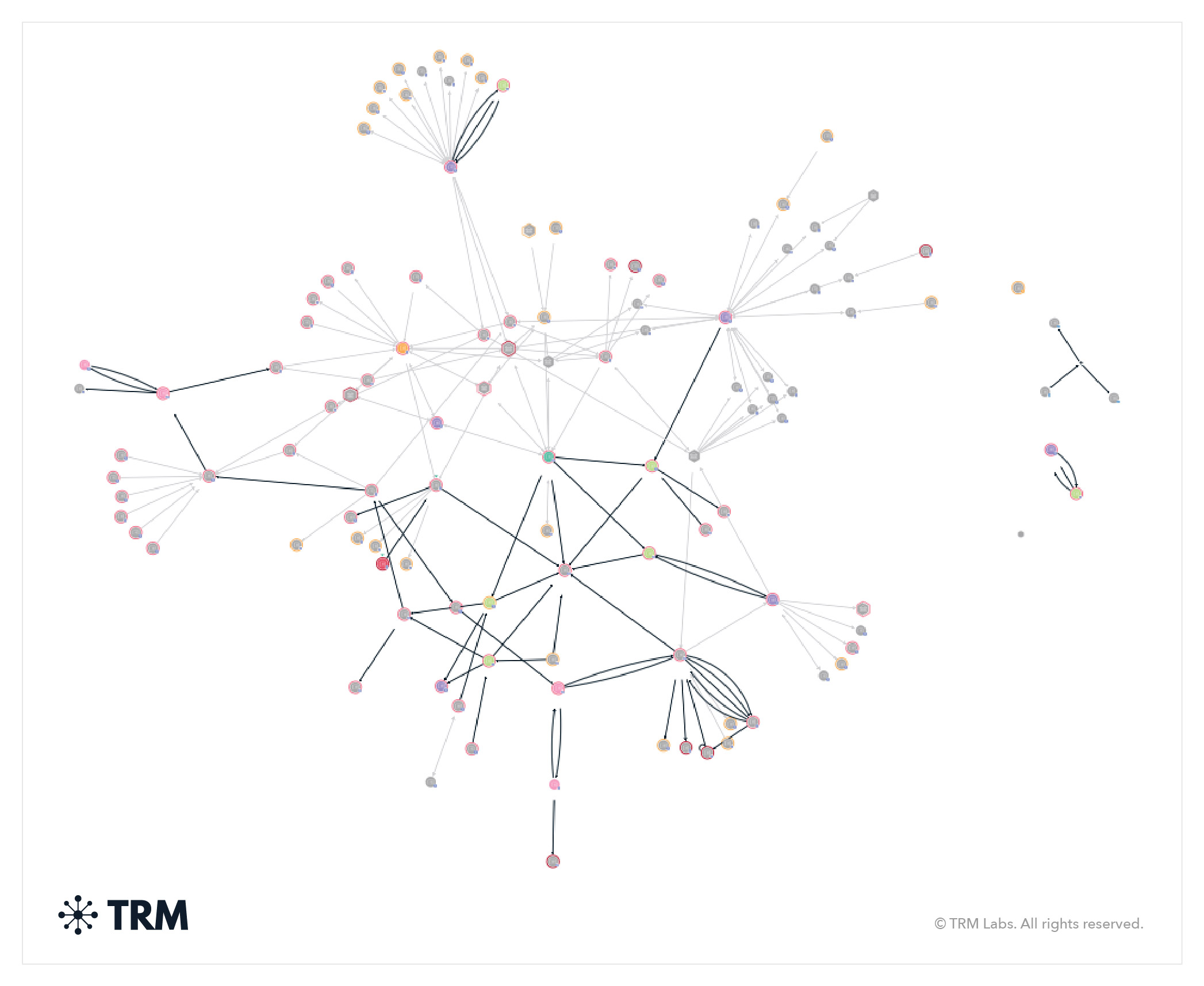

Ponzi and pyramid schemes generally have the most complicated on-chain activity of all the other scams typologies covered in this flip book.

Because they do make payouts to investors, it can be hard to determine what might be a withdrawal to an investor vs. a withdrawal to the scheme operator. These types of schemes also often use third party payment processors to accept deposits and make withdrawals to users — complicating the on-chain investigation and sometimes necessitating legal process to identify what activity of the payment processor is related to the scheme.

Ponzi and pyramid scheme operators often have multiple aggregation, intermediary, and withdrawal addresses. Sometimes they have one deposit address per user. And other times they share deposit addresses between users or create new ones for every deposit.

The TRM graph below shows a partial tracing of the deposit and withdrawal infrastructure of the Finiko Ponzi scheme, which sometimes utilized a payment processor for its operations.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">6. Advance fee scams</h3>

In this type of scam, the victim is persuaded to pay a sum of money upfront in the promise of receiving a larger amount of money at a later date. In the context of digital assets, a scammer might promise a large quantity of cryptocurrency in return for a smaller upfront payment.

Inheritance and lottery scams

Usually a type of advance fee fraud, inheritance scams involve criminals often initiating contact via email, social media, or even traditional mail, claiming to be lawyers, representatives of deceased individuals, or family members. In lottery scams, criminals set up websites or send emails claiming that the recipient has won a significant amount of cryptocurrency in a lottery or giveaway.

In both cases, scammers inform the target that they are the rightful heir or beneficiary of a substantial amount of cryptocurrency left behind by a deceased person or won in a lottery. The scammers will often ask the victim for funds on several different occasions to “unlock” the full amount.

What do advance fee scams look like on-chain?

The on-chain activity of advance fee schemes is often fairly straightforward. An investigator might expect to see payments being made via cryptocurrency ATM to an address, which then sends the user’s funds to a service in a couple of hops.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">7. Pump-and-dump scams</h3>

In these schemes, scammers will heavily promote a particular cryptocurrency to inflate its price (the "pump"). Once the price has risen significantly, they sell off their holdings in that currency, causing the price to crash (the "dump").

The scammers profit, while those who bought in during the "pump" phase lose money. In many pump-and-dump schemes, the scammer misrepresents the total assets associated with the scheme and/or the scammer’s beneficial interest in the assets.

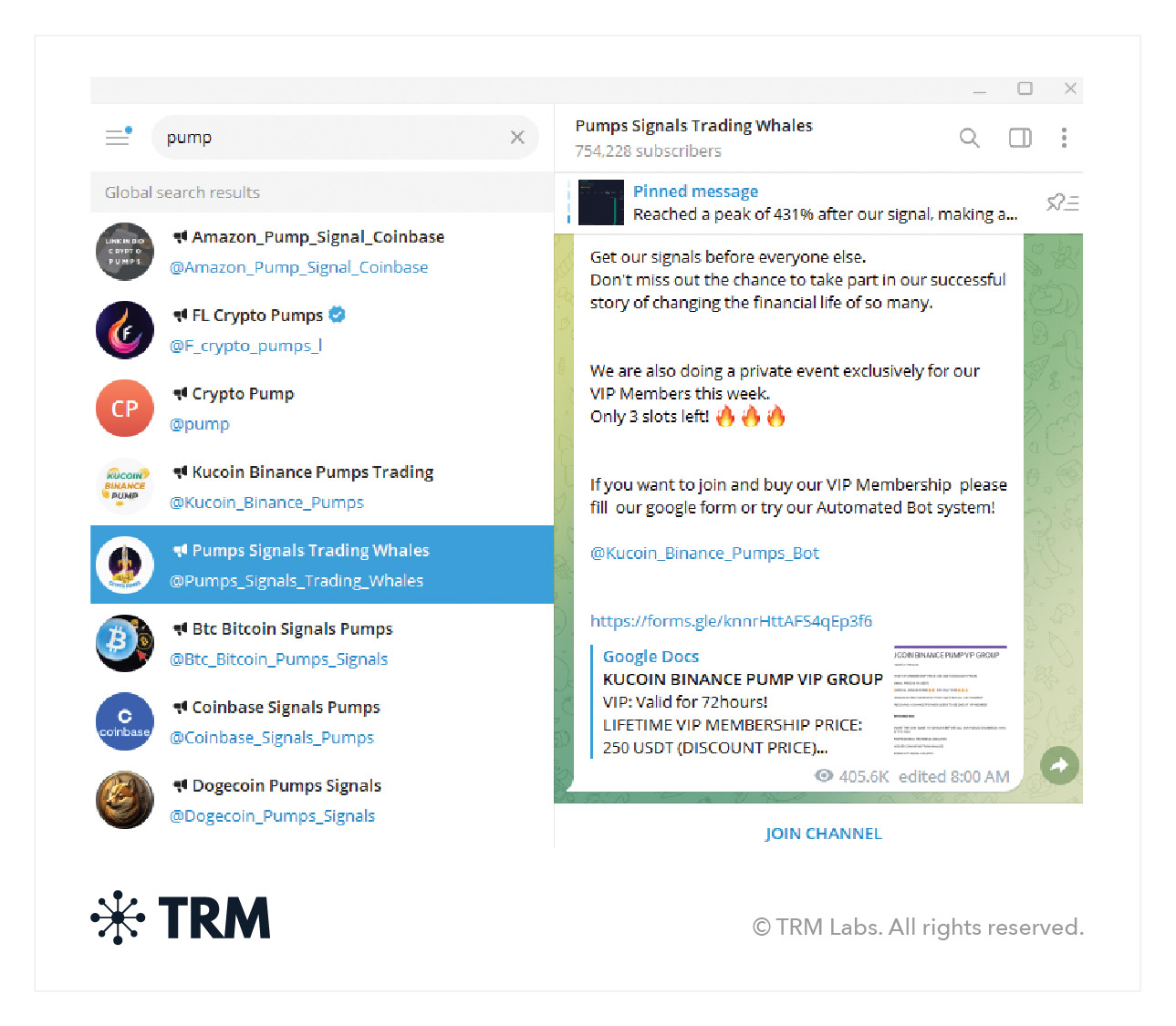

Many crypto pump-and-dump groups, often called “signals” groups, exist on Telegram. Operators claim they can conduct market manipulation for the benefit of the members of the group — when in reality, the profits are likely only being made by the top players and organizers.

What do pump-and-dump scams look like on-chain?

On-chain, we generally see evidence of a high volume of trading when the token is being pumped. And on price-watching applications (available at many exchanges and other services), you might see the price spike suddenly before either gradually or suddenly falling.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">8. Phishing scams</h3>

In the context of crypto, phishing scams involve scammers impersonating a reputable cryptocurrency service (like a wallet or exchange) and sending victims emails, text messages, social media messages, or even cryptocurrency tokens with a link to a fraudulent website.

Scammers will sometimes even create fake Google ads hoping that when an individual searches for the legitimate site, they’ll accidentally click on their link in the search results and land on the phishing site instead. The aim is to trick the victim into entering their login credentials or seed phrase, which the scammer then uses to access the victim's account and steal their funds.

NFT bait-and-switch phishing scams

Bait-and-switch phishing scams prompt users to sign a contract — usually under the pretense of a legitimate transfer of ownership — which then grants control of the user’s entire wallet to the attacker.

Here are the steps phishing scammers typically follow:

- The attacker sets up a wallet

- The attacker creates a contract. The bait-and-switch contract includes code functions that may allow an attacker to transfer all of the victim’s tokens from the victim’s wallet.

- The attacker deploys a contract initiating the transfer

- The attacker phishes the victim. The actual phishing can take different forms — including emails, direct messages in messaging apps, pop-ups on forums, in-wallet ads, fake sites with wallet connections, and impersonations of support staff on NFT markets. In the end, the victim is always asked to either provide private keys or sign approval contracts. These attacks are successful because buyers and sellers are under pressure to act fast to collect valuable NFTs.

- The attacker steals the NFT

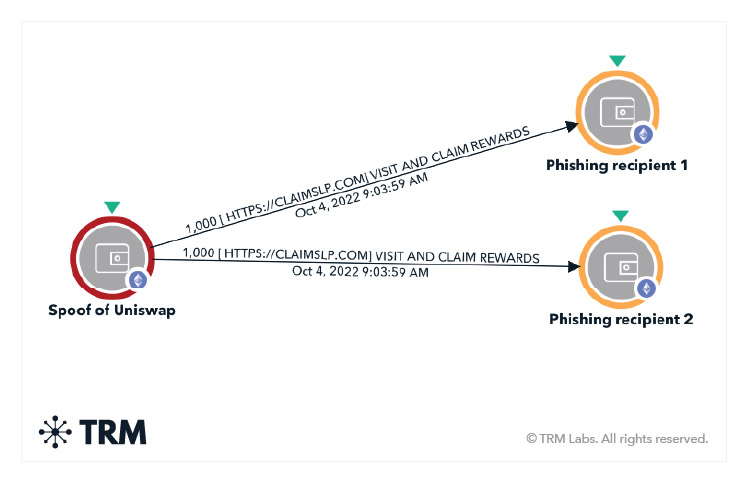

AirDrop phishing

One common form of phishing involves AirDropping tokens to users’ wallets, with the goal of getting the users to research the token and end up on a website controlled by the scammer. From there, the scammer will steal the user’s login information or enable an approval that allows the scammer to remove funds from the user’s wallet.

What do AirDrop phishing scams look like on-chain?

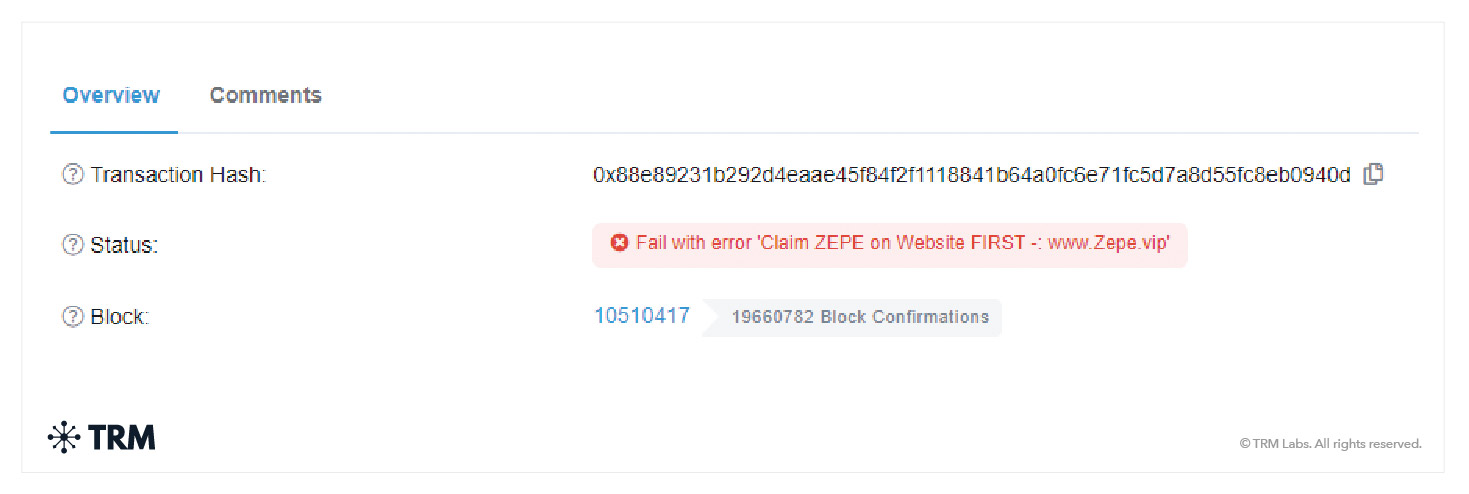

In the TRM graph below, the token name is the phishing website name. The scammer sent the tokens to thousands of users and also spoofed UniSwap to make it look like UniSwap was the one AirDropping the tokens when in fact, they did not.

In another form, the scammer might purposefully carry out the AirDrop incorrectly to get the user to visit a block explorer, where the user might see something like the image below, prompting them to visit the token’s website.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">9. Drainware</h3>

Drainware is a form of cryptocurrency fraud in which attackers manipulate wallet infrastructure or smart contract vulnerabilities to secretly siphon off funds from unsuspecting users. The draining occurs when a user unknowingly connects and signs a transaction attempting to either purchase and mint an NFT, or through interaction with a phishing website that is imitating a legitimate crypto service. Unlike traditional malware, drainware typically operates through exploiting gaps in wallet or smart contract security, rather than through direct device infections.

Drainware contracts are considered malicious because they are specifically designed with the purpose of theft and have no other legitimate uses. Drainer Templates as a Service (DTaaS) have also surfaced, providing attackers pre-built, ready-to-launch drainware templates.

What do drainware scams look like on-chain?

Drainware attacks often go unnoticed because the funds are drained slowly and over a longer period, making it difficult to trace or identify. This is especially dangerous because it enables fraudsters to evade detection by traditional security measures, allowing them to quietly move assets without triggering immediate alarms.

Examples of drainware attacks include those targeting decentralized finance (DeFi) platforms, where attackers exploit vulnerabilities in smart contracts to redirect a portion of the assets stored within them. Another common scenario involves malware that is subtly added to a cryptocurrency wallet, where the malicious code transfers small amounts of funds from the wallet over time to an address controlled by the attacker. The funds are often moved in such a way that it appears as if the transaction is part of normal wallet activity, making it hard for users to notice until significant amounts have been drained.

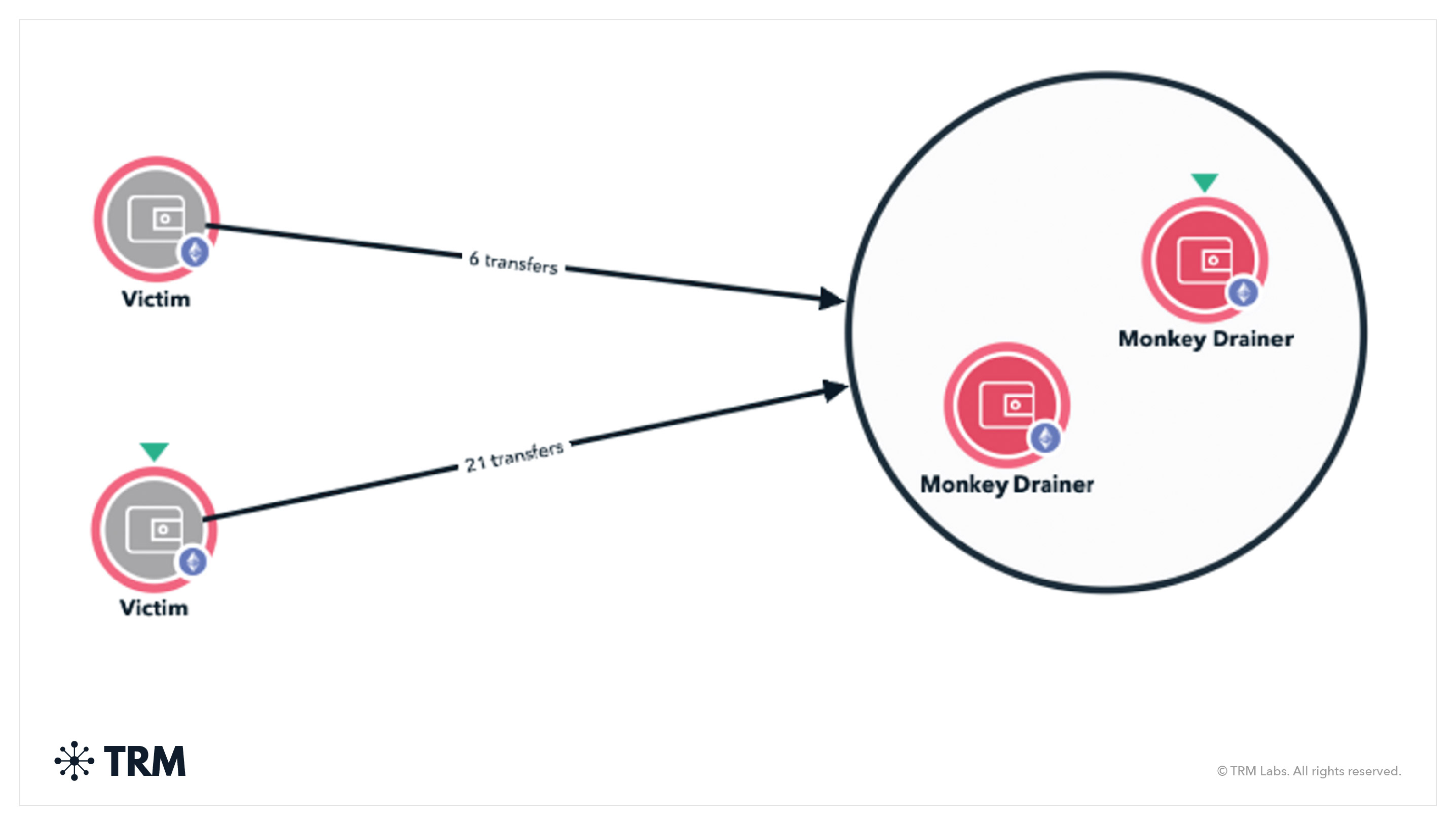

In 2023, the malicious Monkey Drainer attack became one of the most significant drainware threats targeting the crypto industry. This attack — which only required users to approve and sign transactions — simplified the process for fraudsters compared to many traditional methods. First identified by on-chain investigator Zachxbt, who linked the attack to over USD 3.5 million in stolen cryptocurrency, Monkey Drainer exploited user wallets to drain funds in a highly effective manner. Over a 24-hour period, 700 Ethereum were stolen, and a total of 7,300 transactions occurred over two months.

As reported on Chainabuse, users flagged addresses associated with the attack, confirming the use of Tornado Cash to launder stolen funds. The stolen assets — including high-value NFTs such as Crypto Punks and Otherside Meta — were moved through intermediary wallets before being cashed out via centralized exchanges.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">10. Mining scams</h3>

These scams promise victims high returns from participating in cryptocurrency mining, often asking for an upfront payment for "shares" in a mining pool. However, the mining pool either does not exist, does not pay out the returns that were promised, or turns out to be a Ponzi or pyramid scheme (as in the example below).

A popular form of the mining scam is a “USDT Mining” scam, which tells users they’re mining USDT, usually on TRON, which is not actually possible. “Liquidity mining” was a popular term used by pig butchering schemes in the past, though it appears less common today.

What do mining scams look like on-chain?

Mining scams, often disguised as legitimate investment opportunities, typically exhibit on-chain patterns consistent with pyramid and Ponzi schemes. These scams generally promise high returns on investments made in mining operations, but often fail to deliver actual mining activity. Instead, scammers use the new investments to pay returns to earlier investors, creating the illusion of profitability.

On the blockchain, this results in frequent large fund movements between wallets, often in a circular pattern that is designed to obscure the true flow of funds. These wallets may also show a high volume of transactions to and from centralized exchanges or mixing services to hide the stolen assets. Additionally, fraudulent mining schemes may rely on "exit scams" — where the operators suddenly disappear after accumulating significant funds, leaving investors with no recourse to recover their assets.

Key red flags for mining scams include unrealistic promises of returns, the lack of verifiable mining operations, and suspiciously high transaction volumes linked to opaque wallet addresses.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">11. Tech and IT support scams</h3>

These schemes involve scammers posing as technical support personnel or representatives of cryptocurrency platforms to deceive victims and steal their funds or sensitive information — often exploiting the victims' lack of technical knowledge or familiarity with cryptocurrencies.

Here are the steps tech and IT support scammers typically follow:

{{investigating-crypto-scams-tech-support-scams-dropdown-1}}

{{investigating-crypto-scams-tech-support-scams-dropdown-2}}

{{investigating-crypto-scams-tech-support-scams-dropdown-3}}

{{investigating-crypto-scams-tech-support-scams-dropdown-4}}

{{investigating-crypto-scams-tech-support-scams-dropdown-5}}

{{investigating-crypto-scams-tech-support-scams-dropdown-6}}

What do tech and IT support scams look like on-chain?

The on-chain activity of these types of scams tends to be relatively simple. The TRM graph below shows an example of the victim sending funds to the scammer’s address via ATM before the scammer then sends it directly to an exchange. The scammer might also send the proceeds directly through a mixer to attempt to obfuscate the source of funds.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">12. Impersonation scams</h3>

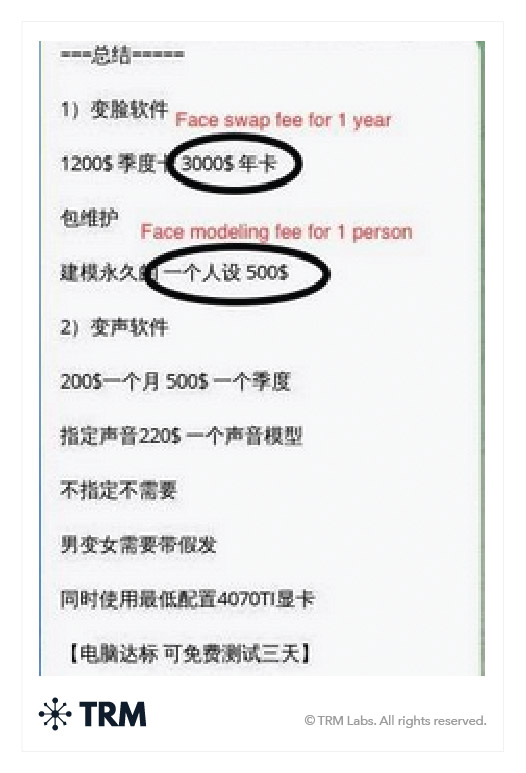

Impersonation scams involve scammers pretending to be someone they are not — often a trusted entity like a bank, government agency, or even a friend or family member — to trick victims into giving them money or personal information. Increasingly, scammers are even using deepfakes to impersonate company executives as well as members of the public.

Scammers may impersonate a government agency, such as a tax authority or law enforcement agency, and threaten the victim with claims such as: “You owe taxes; send us money or you will be arrested.” Or they might impersonate a member of the victim’s family and claim to be hurt, in trouble with the police, and in need of money (in the form of crypto).

What do impersonation scams look like on-chain?

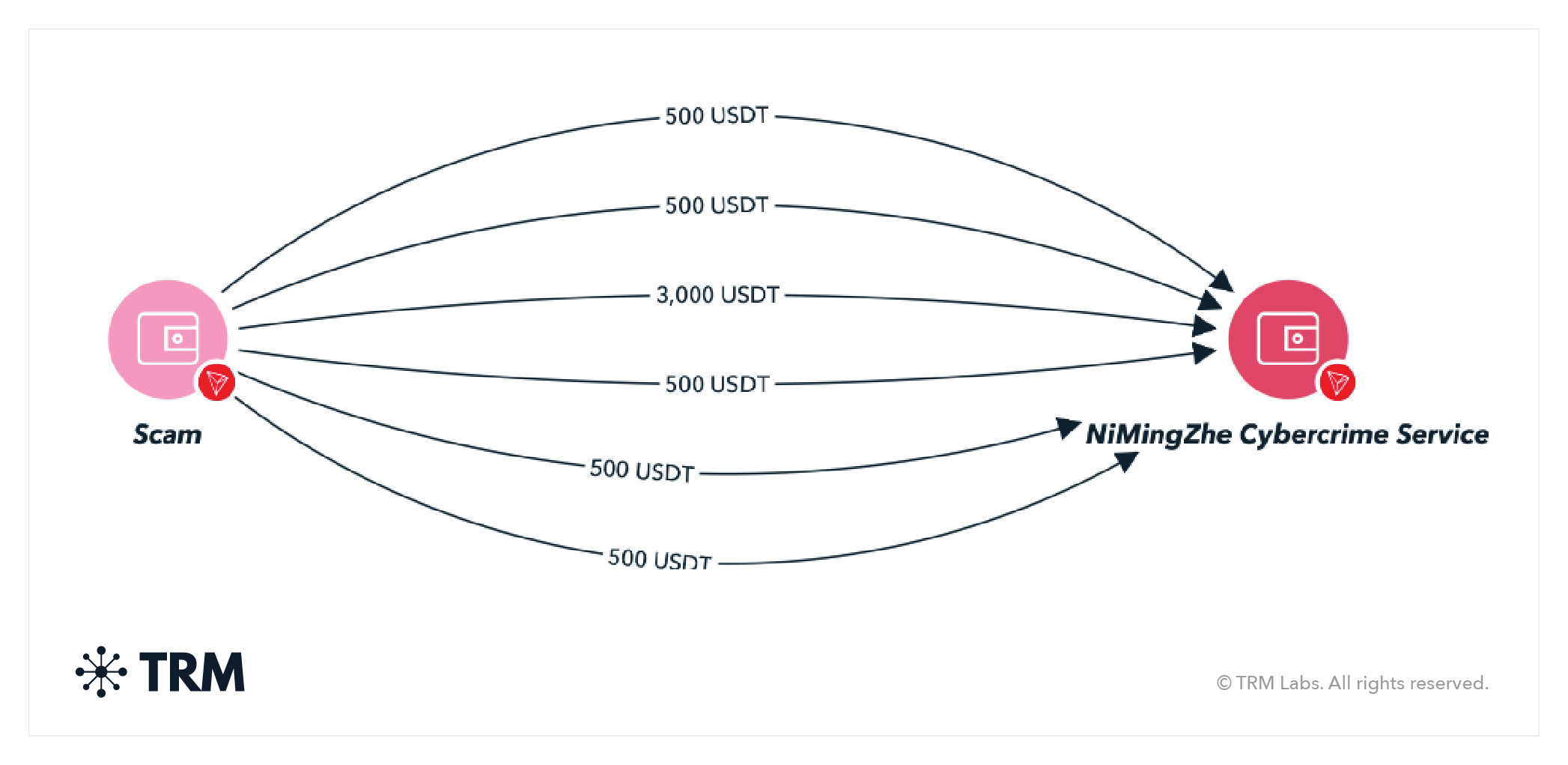

Live deepfakes, which overlay a person’s face on top of another’s in a live video call, have added a new, sophisticated element to impersonation scams — and do not require criminals to collect a large volume of data on their victims. Now, scammers can replicate a person’s voice or image based on just a few seconds of video or audio.

TRM has observed crypto payments from pig butchering scams, as well as investment scams, to deepfake-as-a-service providers. The surge in deepfake-as-a-service — and AI-as-a-service more broadly — indicates the growing demand for the technology, likely from organized criminals.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">13. Extortion scams</h3>

Similar to impersonating the government, in extortion scams, scammers will claim something bad will happen to the victim if he or she does not send crypto to the extortionist. The bad event could be any number of threats — including exposing personal, family, or business information; threat of government action or inaction; threats of cyber intrusions; or even threats of physical violence.

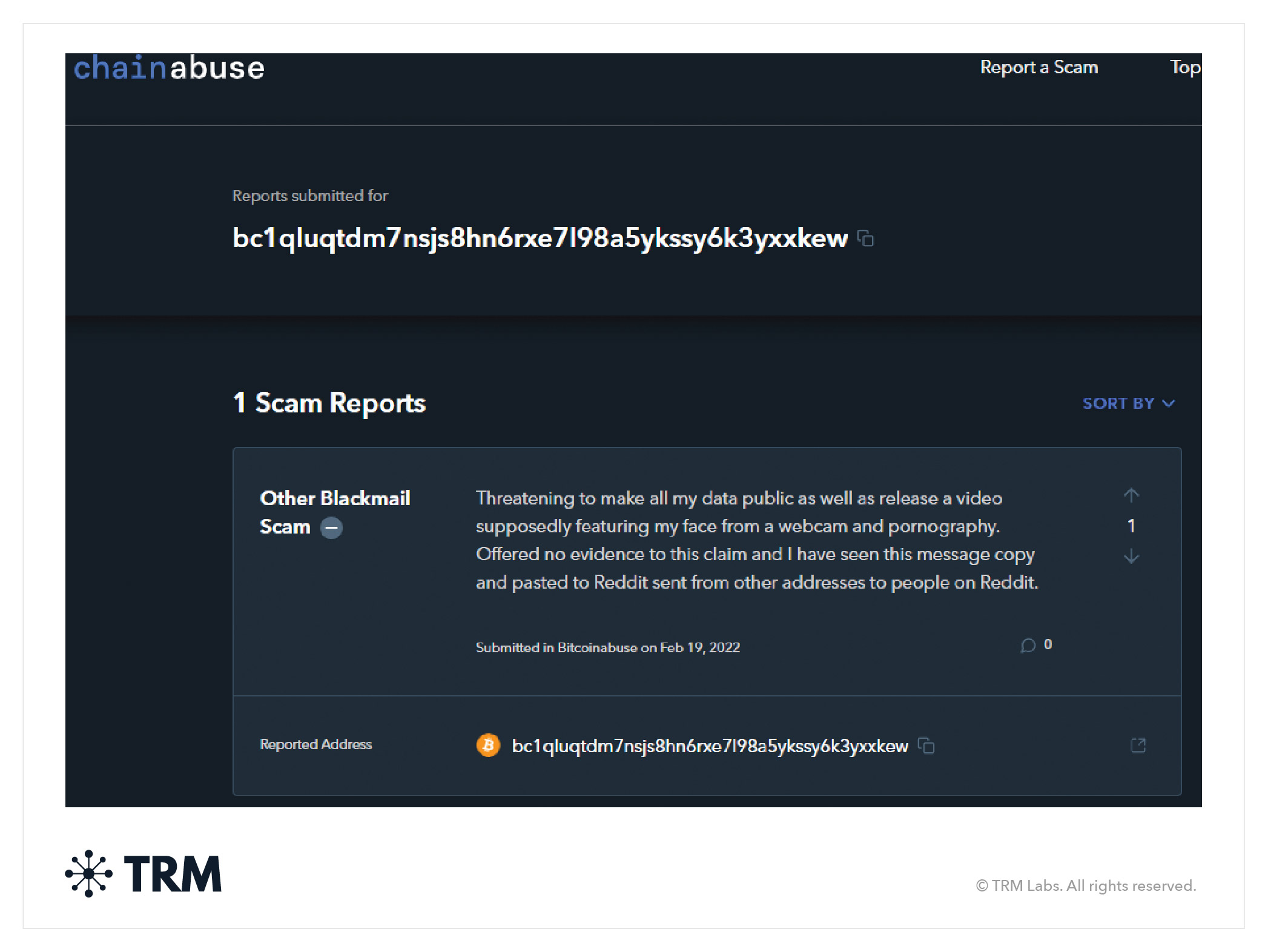

A common type of extortion is the “sextortion” scam, where scammers will send users messages saying they have hacked their computer, accessed their webcam, and obtained compromising photos or videos of the victim before demanding payment for not releasing the footage.

What do extortion scams look like on-chain?

On-chain, extortion scams often manifest as transactions sent from the victim's wallet to the scammer's address, sometimes with a sense of urgency or a deadline for payment. These transactions can be traced through repeated wallet interactions or a series of small payments over time, indicating an ongoing attempt to extort the victim.

Although the actual threats are made off-chain through direct communication or messaging platforms, the on-chain activity serves as the financial transaction that facilitates the scam, with funds often being moved across multiple addresses to obscure their origin and destination.

<h3 class="premium-components_show-toc">14. Money mule scams</h3>

In money mule scams, scammers recruit individuals — known as money mules — to facilitate the transfer of illicit funds obtained through illegal activities. In the context of cryptocurrencies, money mules are used to move and launder money earned through various fraudulent activities, such as phishing, hacking, or cryptocurrency investment scams. The money mules may be asked to send some of their own funds to the scammers as well. Mules typically don’t know that they are conducting illicit activity.

What do money mule scams look like on-chain?

In money mule scams, criminals typically send their illicitly earned crypto to mules at exchanges or peer-to-peer services to have them move funds on their behalf. On-chain activity in these scams often follows a clear pattern of moving funds through multiple wallets in an attempt to obscure the origin of the illicit cryptocurrency. The stolen funds are typically sent to the mule's wallet, which could be a centralized exchange or peer-to-peer service, where the funds are then transferred or withdrawn.

These transactions may seem legitimate on the surface, as mules are usually unaware they are participating in illicit activities. However, patterns of rapid fund movement, along with interactions with known high-risk addresses or exchanges, can raise red flags. In some instances, mules are instructed to withdraw funds and send them to other individuals or exchanges, further complicating the tracing of illicit activity. Blockchain intelligence tools are crucial in identifying these patterns, highlighting suspicious transactions, and helping investigators track and dismantle money laundering schemes.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

Investigating crypto-facilitated scams

<h3 class="premium-content_subhead">How to use blockchain intelligence to investigate cryptocurrency-based scams</h3>

There are many paths to success in disrupting cryptocurrency-based scams and frauds. And though the specific tactics criminals leverage to carry out these crimes can vary significantly — as can the laundering techniques they use to conceal the source and destination of the fraudulent proceeds — blockchain investigators should have two primary goals in mind when opening a cryptocurrency-based fraud investigation:

{{investigating-crypto-scams-primary-goals-callout}}

In this section, we’ll walk through six recommended steps to consider in every blockchain investigation, with the goal of helping you successfully identify the scammers and forfeit misappropriated funds:

- Identify transactions associated with the scam

- Trace the proceeds of the scam on the blockchain

- Identify and request records from third parties with exposure to the scammer or their proceeds

- Request legal process and production of records from third parties

- Freeze and/or seize all assets associated with the scam

- Identify and charge scammers with violations of criminal law

1. Identify transactions associated with the scam

Details of a scam may come to law enforcement in many ways. An investigator may take a victim complaint, read a report from a public scam reporting website like Chainabuse, or read about a scam in a suspicious activity report (SAR). But one common trait across most scams is that fraudsters often “cash out” proceeds from their fraud schemes within 24 hours — making speed critical when carrying out blockchain investigations.

It’s important to move quickly to:

- Verify the reported loss amount

- Determine if stolen assets are still in the cryptocurrency ecosystem

- Ascertain whether there is a third party that can be contacted to learn the disposition of funds and/or the identity of the fraudsters

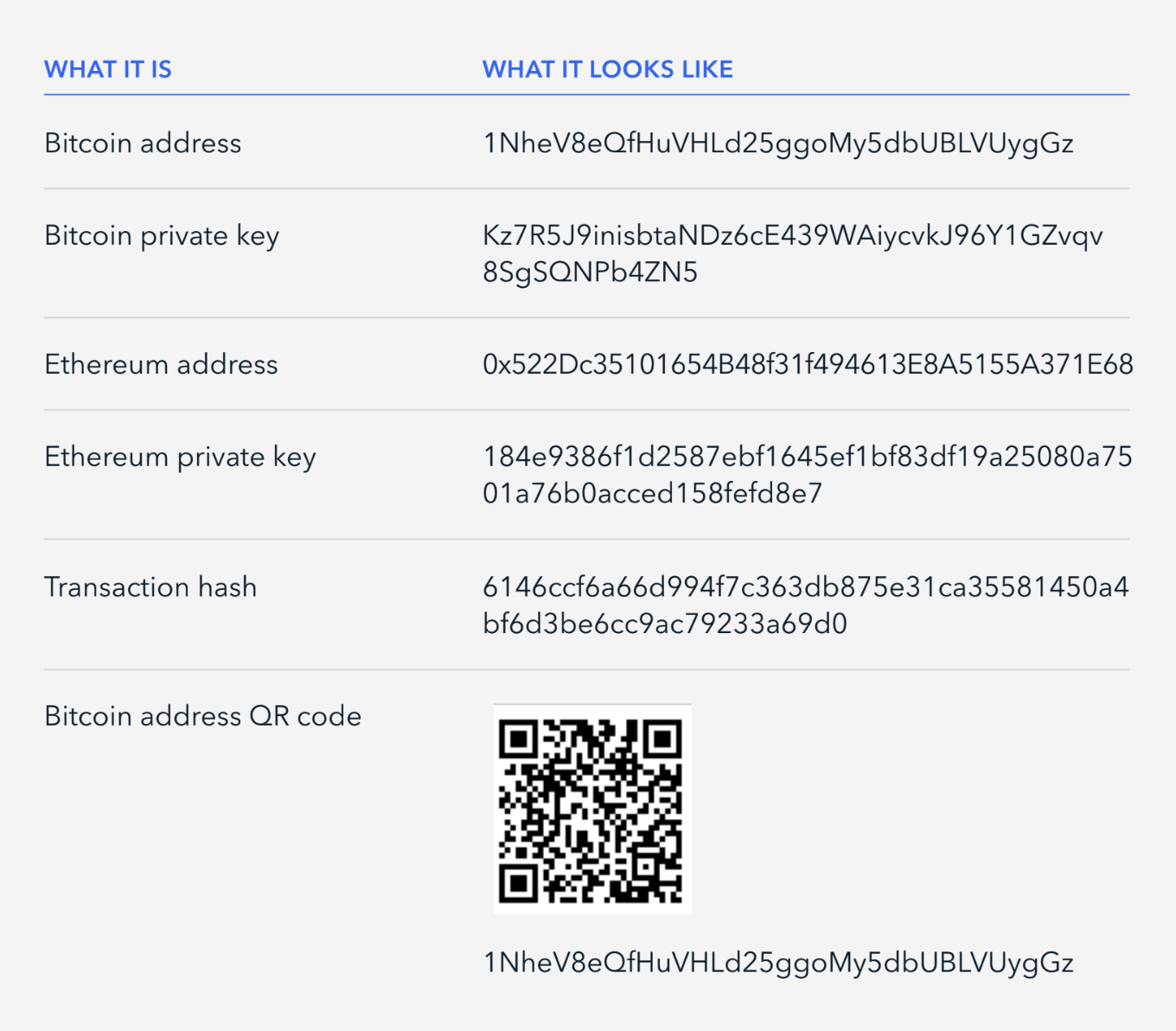

Your first step should always be to identify virtual currency addresses and transaction IDs within the complaint. Look for the following types of alphanumeric sequences, QR codes, and transaction IDs in order to quickly learn about the addresses involved in a scam.

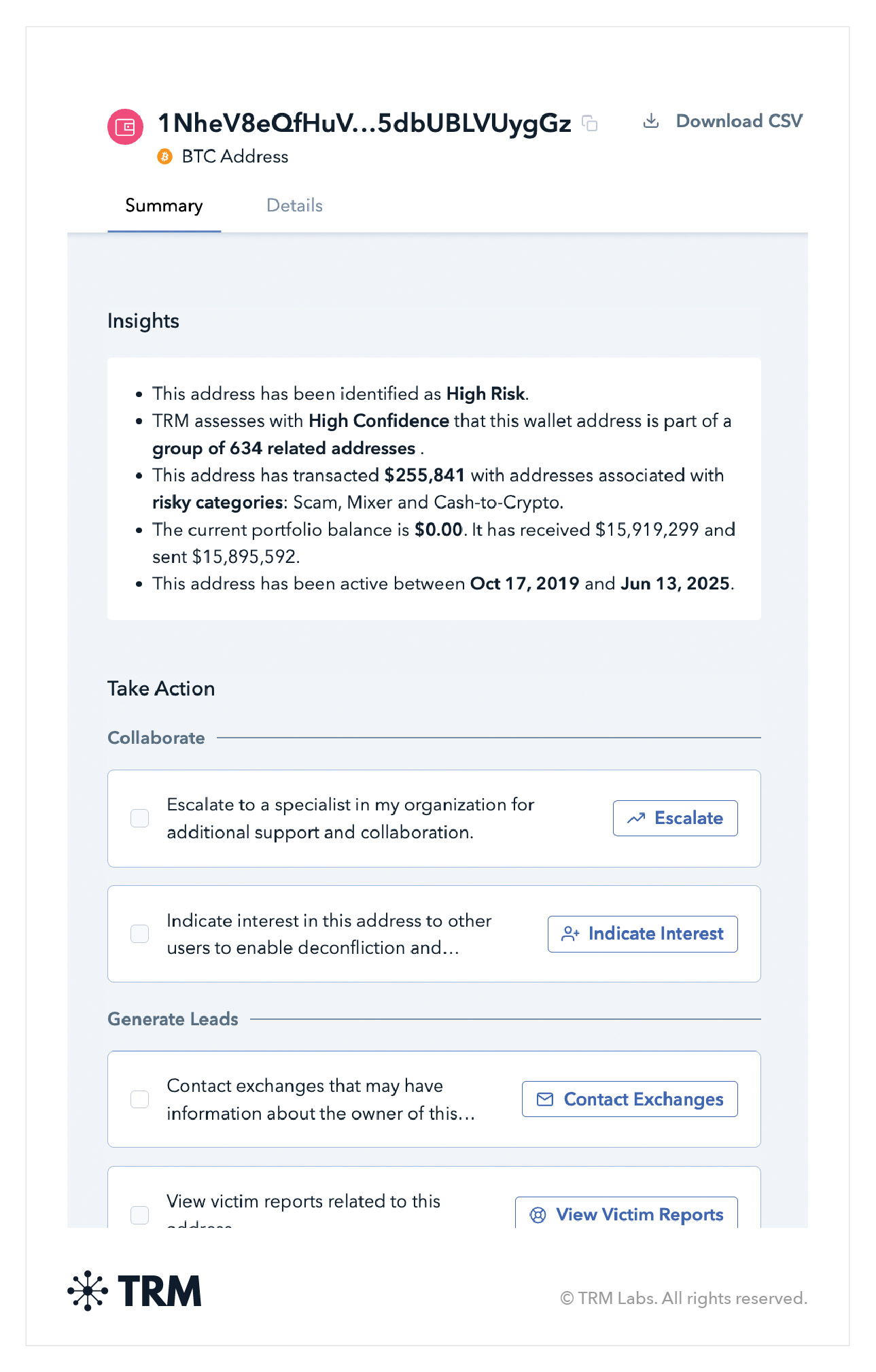

After identifying the addresses and/or transaction hashes, input the information into a blockchain intelligence tool like TRM Triage or TRM Forensics to learn about the transactions.

For example, a non-specialist on the frontline using TRM Triage can quickly search the address and instantly get a summary of the address’ risk level, value, and activity — as well as quickstart actions to escalate to other more specialized investigators or contact exchanges.

2. Trace the proceeds of the scam on the blockchain

After you’ve obtained a snapshot of the alleged scam from a blockchain intelligence tool like TRM Triage, you can quickly begin tracing the proceeds forward and backwards from the fraudulent transaction(s) in a more comprehensive blockchain intelligence platform like TRM Forensics. This will enable you to potentially identify “cash-out” points, or even other victims.

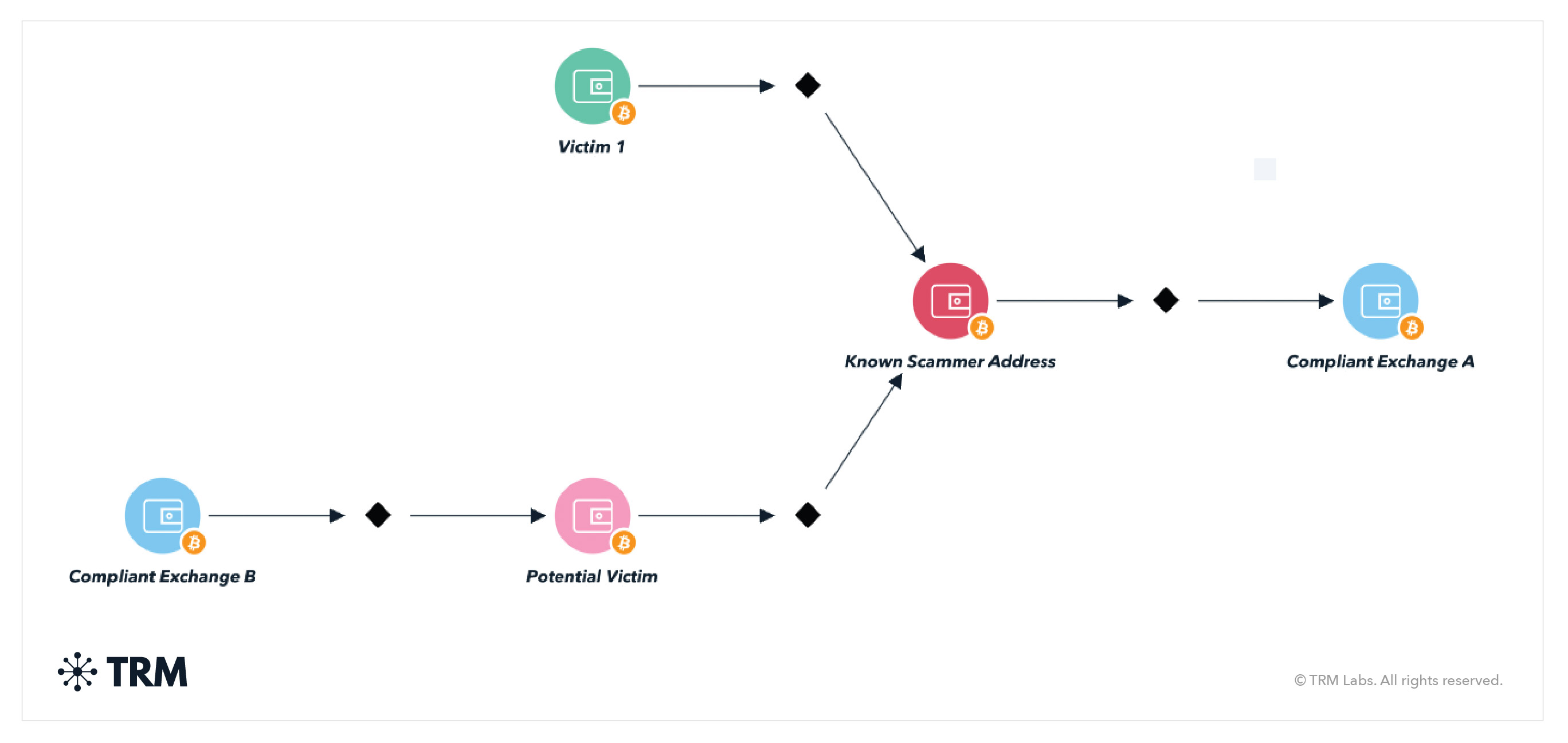

Let’s use the TRM Forensics graph below as a sample investigation.

“Victim 1” informs you that they sent funds to the “Known Scammer Address.” As the investigator, you should:

- Copy/paste the receiving address (“Known Scammer Address”) into blockchain intelligence software like TRM

- Identify subsequent addresses which received funds from “Known Scammer Address” — in this case, “Compliant Exchange A”

- Once you’ve traced funds from “Victim 1” to “Known Scammer Address” to “Compliant Exchange A,” ask “Compliant Exchange A” to freeze the funds and produce records associated with the controller of the address

- Trace backwards from the “Known Scammer Address” to identify additional potential victims — in this case, the “Potential Victim” address. There is considerable likelihood that any additional incoming funds to “Known Scammer Address” are also proceeds of fraud.

- To identify the controller of the “Potential Victim” address, trace backwards to the origination of the funds — in this situation, “Compliant Exchange B.” “Compliant Exchange B” may be able to provide records that reveal the identity of the individual controlling “Potential Victim” address.

TRM Forensics

Blockchain intelligence tools such as TRM Forensics provide enriched blockchain data, which includes attribution, open source intelligence, pattern recognition, visualization functions, and other features to help accelerate investigations. TRM Forensics includes enriched data and blockchain intelligence related to 100+ different blockchains, thousands of different virtual currencies, and millions of addresses — all within an easy-to-use web interface.

These features allow you to quickly follow funds from inception to disposition and can aid in quickly identifying the scammer and/or freezing and seizing stolen assets.

Free blockchain explorers

TRM is purpose-built for analyzing blockchain intelligence and conducting comprehensive investigations. But there are also publicly available block explorer tools which allow investigators to conduct rudimentary analyses and manually track the flow of funds. They often provide data such as:

- Transaction information: Search for specific transactions by entering the transaction hash or address. The tools display detailed information about the transaction, including the sending and recipient addresses, transaction amount, timestamp, and transaction status.

- Address information: Enter a specific address into the explorer to view transactions associated with that address.

- Block information: Explore individual blocks within the blockchain. Each block contains a set of transactions, and the explorer provides information such as the block height, timestamp, size, and the list of transactions included in that block.

- Network statistics: View real-time statistics about the blockchain network — including the total number of blocks, transactions per second, network hash rate, and other relevant metrics. This helps users gauge the network's health and activity.

- Token and contract information: Better understand different tokens — including their supply, token holders, contract details, and which address created the smart contract or token.

- Visualization: Some explorers offer visual representations of the blockchain data, such as graphs or charts, to help users understand the network's structure, transaction volume, or address interactions. These visualizations can aid in identifying patterns, trends, or anomalies within the blockchain.

Advanced search and filtering: Narrow down queries and find specific transactions, addresses, or blocks based on various parameters like time range, transaction type, or block height.

3. Identify and request records from third parties with exposure to the scammer or their proceeds

Once you’ve traced funds to and from the scammer's address, you’ll hopefully find “exposure” to an entity that collects and holds records and assets associated with the scammer.

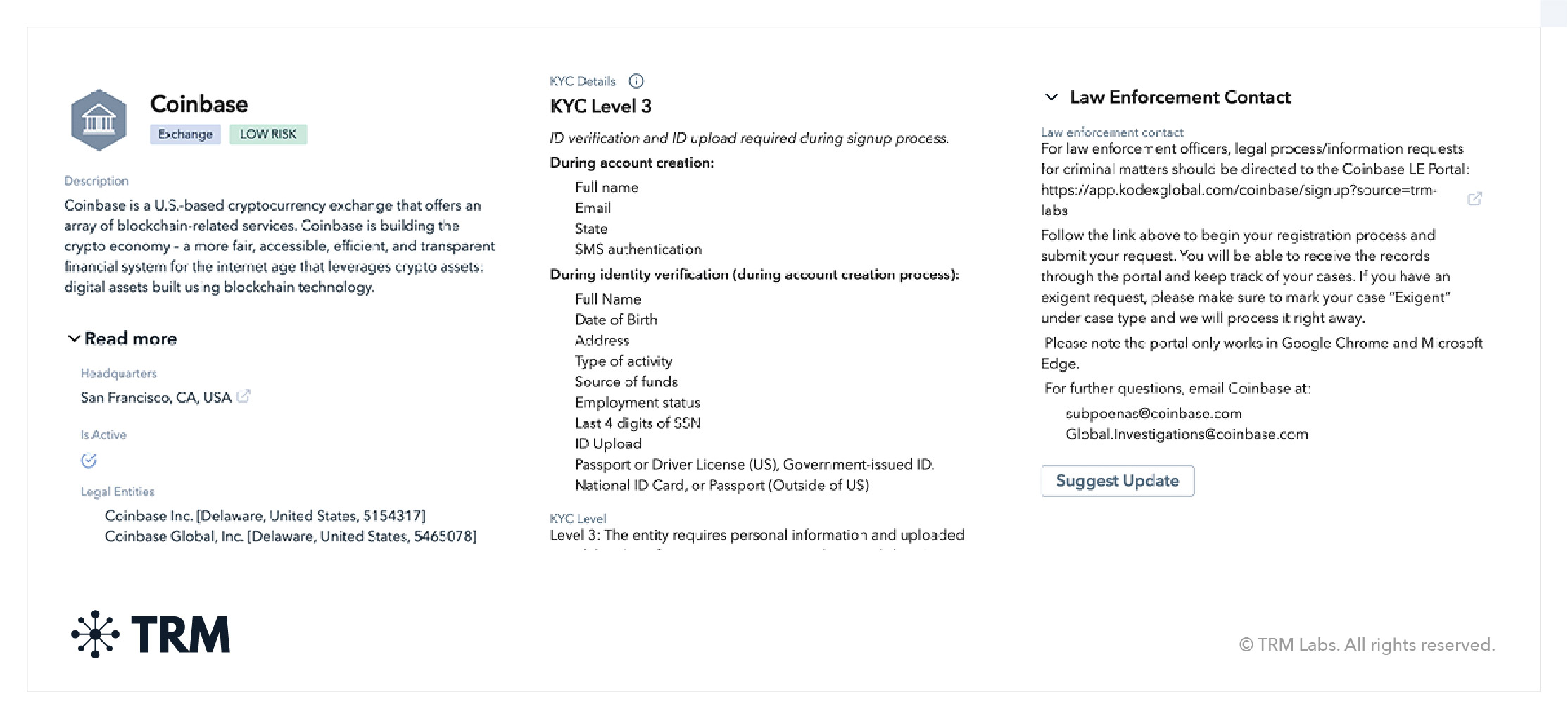

Victims and scammers alike typically use third-party Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs) to convert traditional fiat currency to virtual currency, and virtual currency to fiat currency. Many VASPs collect and maintain a cache of Know Your Customer (KYC) information, many perform asset custody for customers, and many will work with law enforcement to provide records and perform freezes and seizures of illicit funds.

Almost every cryptocurrency-based fraud scheme involves the fraudster sending the proceeds of the scheme to a third party VASP. Identifying and working with these third parties is the key to disrupting the schemes.

4. Request legal process and production of records from third parties

Most third parties and VASPs will work with law enforcement — regardless of the location of the third party and jurisdiction of law enforcement — provided the request is legitimate and the third party’s preferred process is followed. For example, foreign VASPs will frequently work with local, state, and federal law enforcement, even if not compelled to do so by law or treaty.

One way to quickly identify how and where to serve process is to use a blockchain investigation tool like TRM’s Block Explorer, which includes key information such as location, contact information, KYC availability, and financial profile.

You will need to provide the following information to the third party when making a request:

- User information: When requesting information about a specific user or account, such as the victim or fraudster, you should provide any available details about the account holder — for example, the virtual currency address, an account's username or email address, or any other identifiers associated with the account.

- Transaction information: Transaction IDs, wallet addresses involved (including deposit or receiving addresses at the VASP), dates and times of transactions, and any other relevant information that helps the exchange locate the desired transaction records.

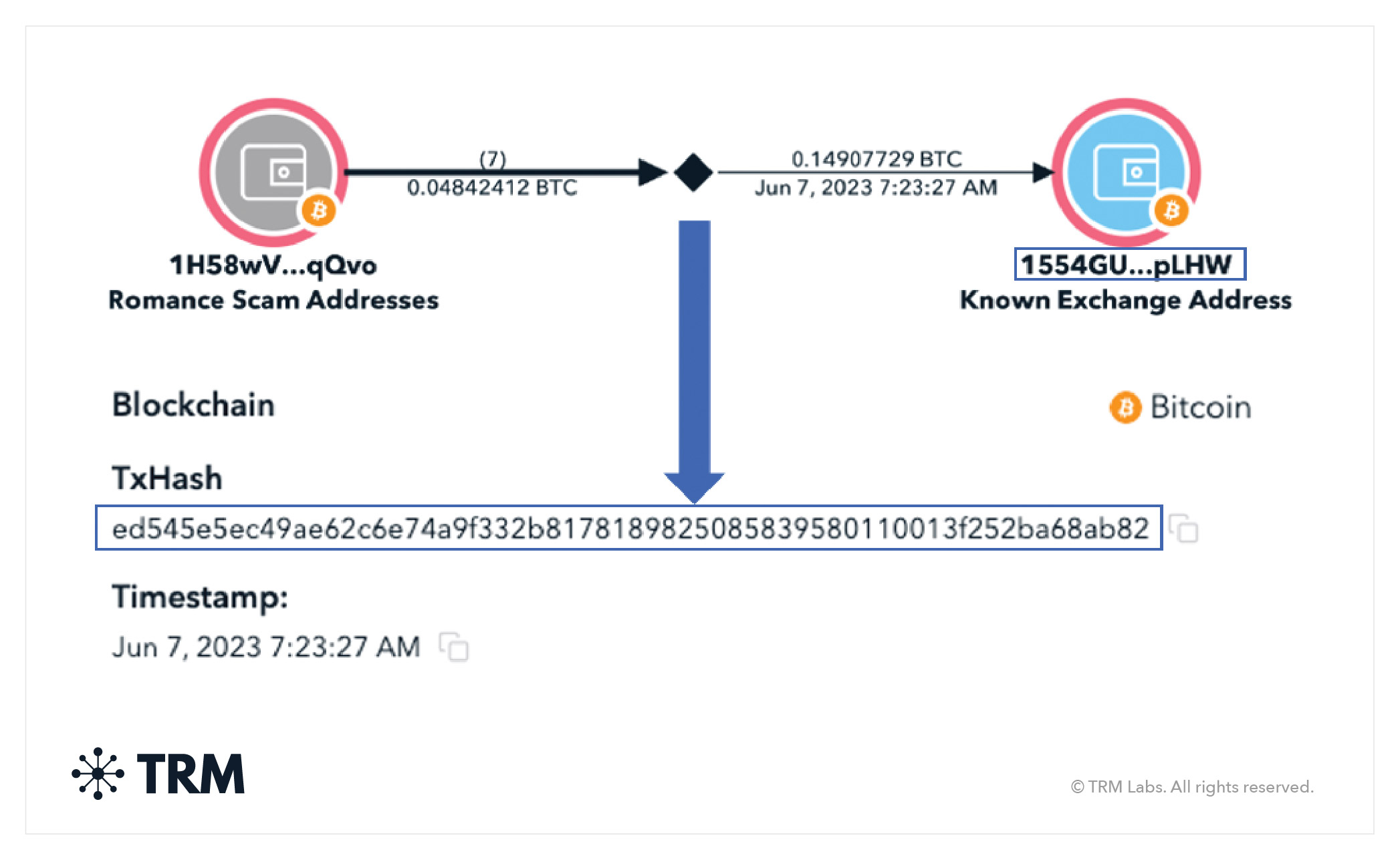

The TRM graph below displays such key pieces of data — namely the deposit address, transaction hash, and transaction timestamp.

If you wanted to seize the assets associated with the transaction above or learn the identity of the controller of the address, you would ask the VASP for all records associated with address “1554GU…pLHW,” which received .14907729 BTC on June 7, 2023 via transaction “ed545e5ec…”

Depending on the level of KYC of an entity, as well as the robustness of the VASP’s compliance program, it may be possible to request and receive the following information about the account:

- Government-issued identification

- Subscriber information such as account holder name, address, date of birth (DOB), country, picture, email address, and IP address

- Associated accounts, such as linked credit cards or bank accounts

- Account balances

- Internal and external transactional history

- Transactional counterparties

- Communications and messaging

- User device IDs

- An omnibus “all records associated with the account and registrant”

{{investigating-crypto-scams-request-legal-process-callout}}

5. Freeze and/or seize all assets associated with the scam

It is important to know that virtual assets CAN be seized. Where there are virtual currency assets involved in the effectuation of a crime, as an investigator, you should endeavor to seize and restrain those assets (also known as pursuing confiscation in many regions) — and ultimately return those assets to victims and disrupt criminal organizations.

Seizing crypto assets comes down to identifying who is in control of the private key that allows for transfer of the funds. Whoever controls the keys controls the asset.

What to do if victim funds are held at a VASP

Contact the VASP

In situations where an identified VASP is in possession of the funds, the seizure must be made from the VASP. Many VASPs will not only accept legal process and judicial documents such as seizure warrants, but also unofficial “requests to freeze” from law enforcement.

Request a freeze

If you find that victim funds are being held at a VASP, immediately contact the VASP where the funds are held, explain the situation, and ask the VASP flag or freeze the transaction. You should also work with partners to obtain judicial documentation of the request to freeze or seize the funds.

Collaborate with VASP investigative teams

Many VASPs have highly skilled investigative units in addition to compliance units. If you need support digging deeper to understand the full scope or complexity of a scam, consider contacting the VASP’s investigative team for help. TRM Labs can usually help provide a point of contact for investigations teams at most VASPs.

Move the funds to a government-controlled wallet

Procedures and opinions differ across jurisdictions and agencies on how best to take custody of seized assets. What is universal, however, is that once a government “seizes” a cryptocurrency asset, it must move that asset into a government-controlled or created wallet.

As an investigator, you must not rely on seizing a cell phone, application, or access to an account to effectuate a seizure — because if anyone else retains the private key to a physically seized wallet, that person can reconstitute the wallet elsewhere and move the funds, even if a subject is incarcerated and their physical wallet is confiscated.

Some law enforcement entities use hardware wallets for seizure, some use electronic wallets, some open accounts at exchanges, and some use a combination of these strategies. Whichever method is pursued, here are some key questions to consider prior to any seizure:

- Who will have access to the private keys of the government wallet (the investigator, the supervisor, in-house forfeiture staff, legal counsel, prosecutor, etc.)?

- Where will the hardware wallet and private key to the account be stored, and who will have access?

- How will the government eventually return the funds to victims or claimants (e.g. will it be liquidated into USD, or returned in the same form it was seized in)?

- If the asset will be liquidated, how will the forfeiture/liquidation be effectuated?

What to do if victim funds are held in an unhosted address

In situations where the fraudster is in control of the private key(s) (e.g. funds stored in a fraudster's unhosted wallet on their phone or laptop), the unhosted wallet’s private key will need to be entered in order to move the funds to a government controlled account.

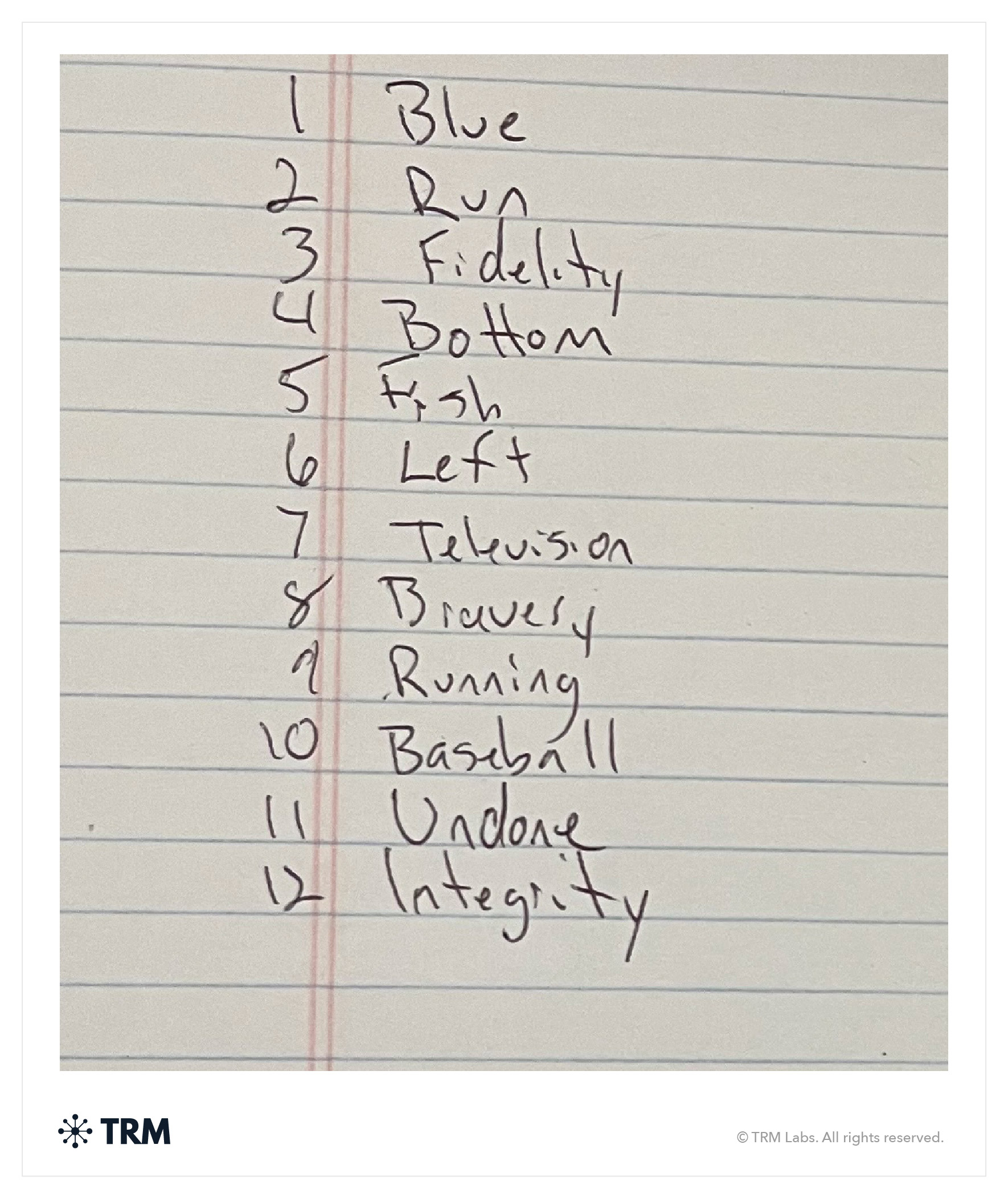

Look for alphanumeric phrases and English word “seed phrases,” which can be back-up private keys. Remember, “seed phrases” are generally 12–24 English language words, sequenced in order, which can be inputted into wallet software to reconstitute a cryptocurrency wallet and send funds.

A typical seed phrase may look like:

6. Identify and charge scammers with violations of criminal law

Many cryptocurrency-based scams span multiple jurisdictions and cross international borders. This makes the charging process onerous and potentially unfruitful, as many jurisdictions are unwilling or unable to prioritize extraditions of scammers. However, there are many reasons for pursuing charges against scammers — even where there may not be a guarantee of incarceration.

Naming and shaming bad actors

Most compliant and professional VASPs employ experienced compliance staff and follow strict compliance protocols. Part of onboarding new customers generally involves a due diligence check where a member of the VASP’s compliance staff may check open source records for negative information about the prospective customer. Where there is a public charge for running a scam, a professional VASP will likely not allow a charged scammer to open an account — making future scams more difficult for them to monetize.

International cooperation

Due to its borderless nature, use of cryptocurrency in scams frequently transcends traditional geographic borders. However, because this is true for all law enforcement entities, there is generally more international cooperation between large and small agencies in an attempt to combat illicit use of virtual currency. Many jurisdictions and agencies are willing to work cases in parallel or jointly with fellow law enforcement agencies, regardless of geographic location.

Charging opportunities

In addition to traditional fraud, theft, or misappropriation statutes, many of the schemes outlined above also trigger sentencing enhancements and increased charging opportunities.

Scammers have also been charged with a range of other criminal offenses — including computer crimes, extortion, racketeering, organized crime, and money laundering, which often lead to significant sentences. Significant sentencing enhancements may also be obtained based on the age or number of victims, use of sophisticated schemes, money moved internationally, and aggregate dollar value of the schemes.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

Gathering evidence and helping scam victims

<h3 class="premium-content_subhead">What to ask victims in crypto-related scam investigations</h3>

When a crypto scam is reported, having the right information up front helps move the investigation forward faster. At the outset of your investigation, be sure to gather these critical details and ask the victim(s) for the following information so you can act swiftly.

1. Start with the basics

- Get the victim’s full name and contact information

- Document the date and time of the scam

- Identify the platform or app where the scam happened and where it started (e.g. WhatsApp)

2. Understand the scam

- Determine the scam typology that took place (e.g. romance scam, investment scam, impersonation scam, etc.)

- Record any available contact information for the scammer (e.g. phone number, email address, username)

- Ask the victim for any links links and/or websites associated with the scam

- Identify any pressure tactics used by the scammer (e.g. urgency, secrecy, returns on investment)

3. Capture transaction details

Document the following information about any and all transactions related to the scam:

- Type of crypto sent to the scammer (e.g. Bitcoin, Ethereum, etc.)

- Amount stolen

- Wallet addresses

- Victim’s sending address

- Scammer’s receiving address

- Transaction hash

4. Look for clues beyond the blockchain

- Ask the victim for screenshots of messages, conversations, or emails exchanged with the scammer

- Document any phishing sites or fake ads the victim visited

- Capture original email headers, file attachments, and links shared by the scammer

- Ask the victim if any other accounts (e.g. email, Telegram, Discord, etc.) were compromised during the scam

5. Help victims track down the details

Encourage victims to look for the information you need in the following sources:

- Their crypto wallet history (e.g. MetaMask, Trust Wallet, etc.)

- Transaction history from crypto exchanges (e.g. Coinbase, Binance, etc.)

- Free online block explorers (e.g. Etherscan), using the transaction hash

6. Submit a report on Chainabuse.com

Encourage the victim to report the scam on Chainabuse.com, the leading reporting platform for malicious crypto activity worldwide. If needed, as the investigator, you can also submit a report on their behalf. Submitting a report ensures the right investigative teams see the details, and helps protect other potential victims from falling prey to the same scam.

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

Resources for identifying and supporting victims

<h3 class="premium-content_subhead">Additional tools and resources for investigating crypto-enabled scams</h3>

In addition to your dedicated account and investigative support teams at TRM, here are some other organizations and resources you can leverage throughout the investigative process.

Chainabuse

https://www.chainabuse.com/

Chainabuse is the leading reporting platform for malicious crypto activity worldwide,powered by TRM Labs. Chainabuse empowers organizations and users to report malicious activity involving crypto across multiple blockchains, while offering free support to victims of scams. Chainabuse is the official reporting partner for Operation Shamrock.

https://safety.chainabuse.com/preventive-education

The Chainabuse Safety Support Center provides preventative education, safety practices, and recovery insights.

Operation Shamrock

https://operationshamrock.org/

An initiative designed to provide law enforcement with education and resources to help them more successfully seize illicit funds and disrupt cybercrime — namely pig butchering scams. Chainabuse’s partnership with Operation Shamrock empowers investigators with streamlined access to consolidated victim reports and data for network analysis — ultimately enabling them to triage reports faster, investigate cases more thoroughly, and identify linked reports more efficiently.

Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3)

https://www.ic3.gov/

Run by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Internet Crime Complaint Center (IC3) is the central hub for reporting cyber crime in the United States.

Federal Trade Commission (FTC)

http://www.reportfraud.ftc.gov/

Fraud, scam, or bad business practice reporting to the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC), whose mission is to prevent business practices that are anticompetitive or deceptive or unfair to consumers and enhance informed consumer choice and public understanding of the competitive process — without unduly burdening legitimate business activity.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

https://www.sec.gov/tcr

Portal for submitting tips or complaints to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) of suspected securities fraud or wrongdoing — including Ponzi schemes, pyramid schemes, price manipulation, insider training, and more — that include assets designated as securities.

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN)

https://www.fincen.gov/resources/filing-information

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) is a bureau of the United States Department of the Treasury that collects and analyzes information about financial transactions in order to combat domestic and international money laundering, terrorist financing, and other financial crimes. The Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) E-Filing System supports electronic filing of BSA forms, such as Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs), through a FinCEN secure network.

Europol

https://www.europol.europa.eu/report-a-crime/report-cybercrime-online

Europol’s mission is to support its European Member States in preventing and combating all forms of serious international and organized crime, cybercrime, and terrorism. Europol also works with many non-EU partner states and international organizations. Most Member States have a dedicated online reporting option in place, linked on the Europol site.

{{investigating-crypto-scams-contact-callout}}

{{premium-content_chapter-divider}}

About TRM Labs

TRM Labs provides blockchain analytics solutions to help law enforcement and national security agencies, financial institutions, and cryptocurrency businesses detect, investigate, and disrupt crypto-related fraud and financial crime. TRM’s blockchain intelligence platform includes solutions to trace the source and destination of funds, identify illicit activity, build cases, and construct an operating picture of threats. TRM is trusted by leading agencies and businesses worldwide who rely on TRM to enable a safer, more secure crypto ecosystem. TRM is based in San Francisco, CA, and is hiring across engineering, product, sales, and data science. To learn more, visit www.trmlabs.com.

.svg)

.png)