North Korea and the Industrialization of Cryptocurrency Theft

Key takeaways

- North Korea stole over half of the total USD 2.7 billion lost in 2025 in crypto hacks.

- Attack targets have shifted from bridges to centralized targets more susceptible to social engineering and developer compromise.

- Laundering is outsourced to the “Chinese Laundromat” — a network of OTC brokers and underground banks.

- To combat this, compliance teams must shift from static blocklists to typology-driven, multi-chain detection frameworks.

{{horizontal-line}}

In 2025, more than USD 2.7 billion was stolen in crypto hacks — and well over half of that total was linked to a single nation-state actor: North Korea. For years, the regime has weaponized crypto theft as a revenue engine for weapons proliferation, sanctions evasion, and destabilizing activity. What the last three years make unmistakably clear is that North Korea is the most sophisticated, financially motivated cyber operator in the crypto theft ecosystem.

The highest-value crypto heists in this period have not turned on smart-contract failures or clever protocol-level exploits. Instead, they reflect a strategic pivot in both targeting and monetization. North Korean operators have moved upstream, attacking the operational infrastructure of centralized exchanges and custodial service providers where single points of failure can unlock massive sums. But their most consequential evolution lies in the liquidation phase.

Rather than cashing out directly, North Korea has effectively outsourced this step to what investigators call the “Chinese Laundromat” — a sprawling, opaque network of underground bankers, OTC brokers, money transmitters, and trade-based laundering intermediaries. These actors wash stolen assets across chains, jurisdictions, and payment rails, ensuring the funds are thoroughly laundered before ever brushing the formal financial system. It is this fusion — state-directed hacking paired with industrial-scale laundering — that has made North Korea the dominant high-value attacker in cryptocurrency today.

Operational shift: From bridge to CEX

The 2023–2025 incident mix in TRM’s internal dataset shows the largest losses clustering in the infrastructure attack category, with hot wallet/key compromise, multi-sig operator compromise, and front-end/third-party takeovers dominating nine-figure cases.

TRM attributes several 2023 marquee hacks (Atomic Wallet, CoinsPaid, Alphapo, Stake.com, CoinEx) and subsequent CEX mega-heists to North Korea, reflecting a pivot from bridges to centralized targets more susceptible to social engineering and web2 supply-chain abuse.

After the original sanctions designation on Tornado Cash, laundering didn’t stop — it fragmented. Chain-hopping (e.g., Avalanche, Tron), bridges, gambling platforms, rebranded mixers like Sinbad (now sanctioned), and multiple layers of intermediating brokers became staples of a multi-service obfuscation stack.

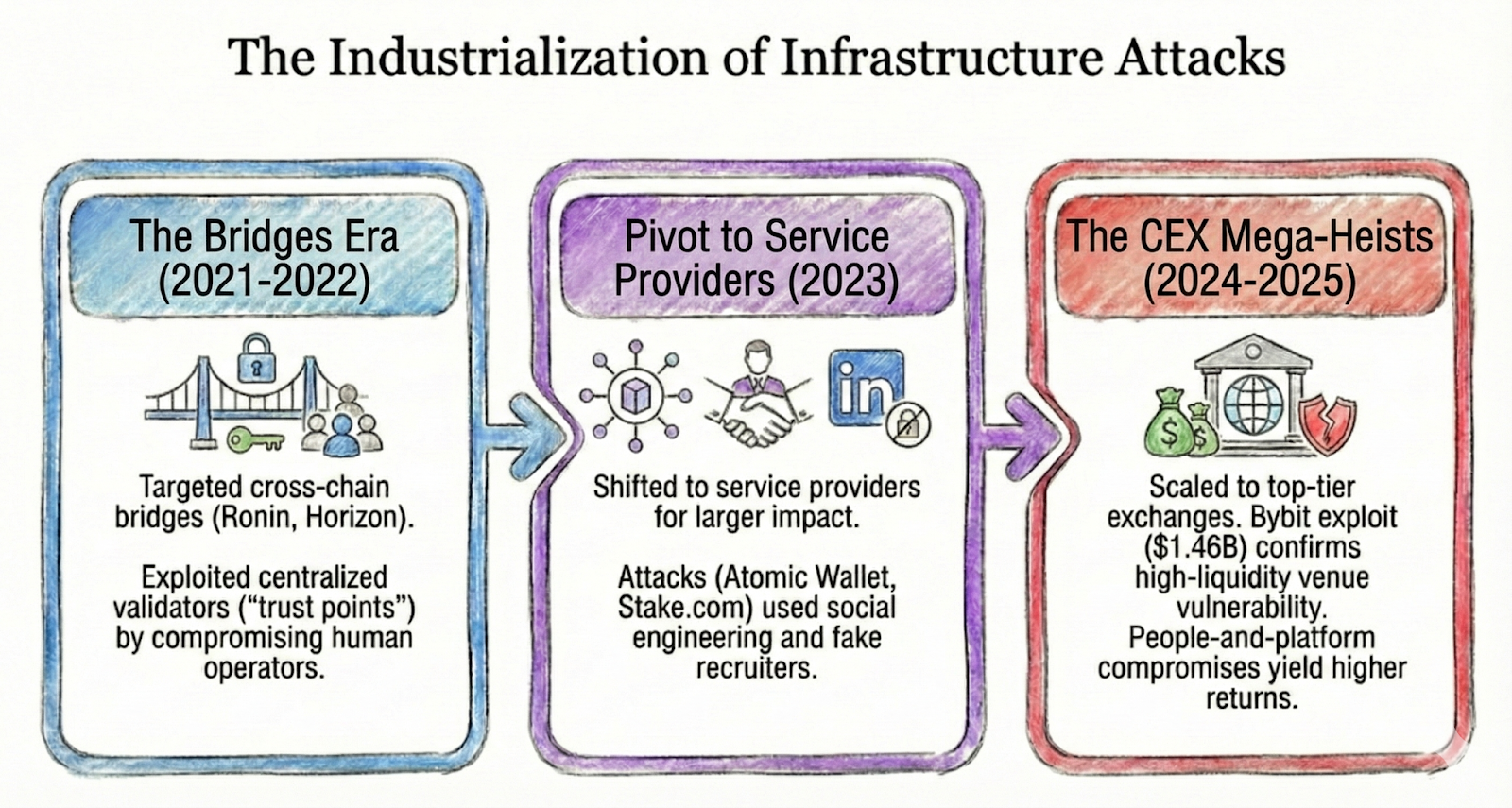

The industrialization of infrastructure attacks

Since 2021, North Korea has systematically graduated to larger targets, moving from decentralized bridges to the centralized giants of the crypto economy, in order to maximize financial returns.

The Bridges Era (2021–2022)

North Korea aggressively targeted cross-chain bridges like the Ronin Network and Horizon Bridge. While these attacks targeted the decentralized finance (DeFi) ecosystem, the hackers bypassed the digital lock entirely. Instead, they compromised "trust points" — the centralized validators holding the keys — thereby establishing a playbook focused on exploiting the people running the systems rather than the code itself.

The Pivot to Service Providers (2023)

By 2023, North Korea realized that centralized service providers offered a potential impact scope significantly larger than individual bridges. A cluster of nine-figure incidents — including Atomic Wallet, Alphapo, and Stake.com — proved that the vector was the human layer. Attacks were often initiated not by hacking, but by social engineering via fake recruiters or LinkedIn credential theft.

The CEX Mega-Heists (2024–2025)

In the current phase, the playbook has scaled to include large, global exchanges. The February 2025 Bybit exploit, which resulted in approximately USD 1.5 billion in losses, suggests that even high-liquidity venues face risks. In this era, people-and-platform compromises yielded consistently higher returns than protocol exploits.

How the tradecraft evolved

While the targets changed, the methods were refined, not reinvented.

Initial access

North Korea’s point of entry overwhelmingly remains the human layer. The entry point is almost always simple: a fake job offer from a 'recruiter' or an investment pitch from a 'venture capitalist' on LinkedIn or a messaging platform.

The victim downloads a 'coding test,' and hidden malware silently steals their credentials. Once attackers compromise a developer workstation, they extract SSH keys, browser cookies, or cloud tokens to move laterally into software deployment systems.

TRM has observed these access pathways in the Bybit and DMM Bitcoin compromises, reinforcing the “Code to Custody” thesis: developer environments are now the most efficient route to exchange-level keys.

Execution

Once inside, the objective is to obtain control over the systems that authorize withdrawals. This typically involves seizing hot-wallet keys, compromising one of several required wallet signers, or infiltrating software development pipelines that govern wallet-orchestration code.

With any of these assets, adversaries can generate valid, key-signed withdrawals that appear operationally legitimate, bypassing both on-chain alarms and most exchange-side anomaly controls. This phase transforms an initial workstation compromise into a full-scale liquidity event.

Obfuscation

Following the heist, the laundering pipeline no longer relies on a simple mixer. TRM investigators noted that the stolen assets immediately fracture into a sequence of chain-hops — often AVAX or ETH into BTC, then into Tron USDT —before vanishing into a service-based ecosystem. This is where the operation leaves the blockchain and enters the "Chinese Laundromat."

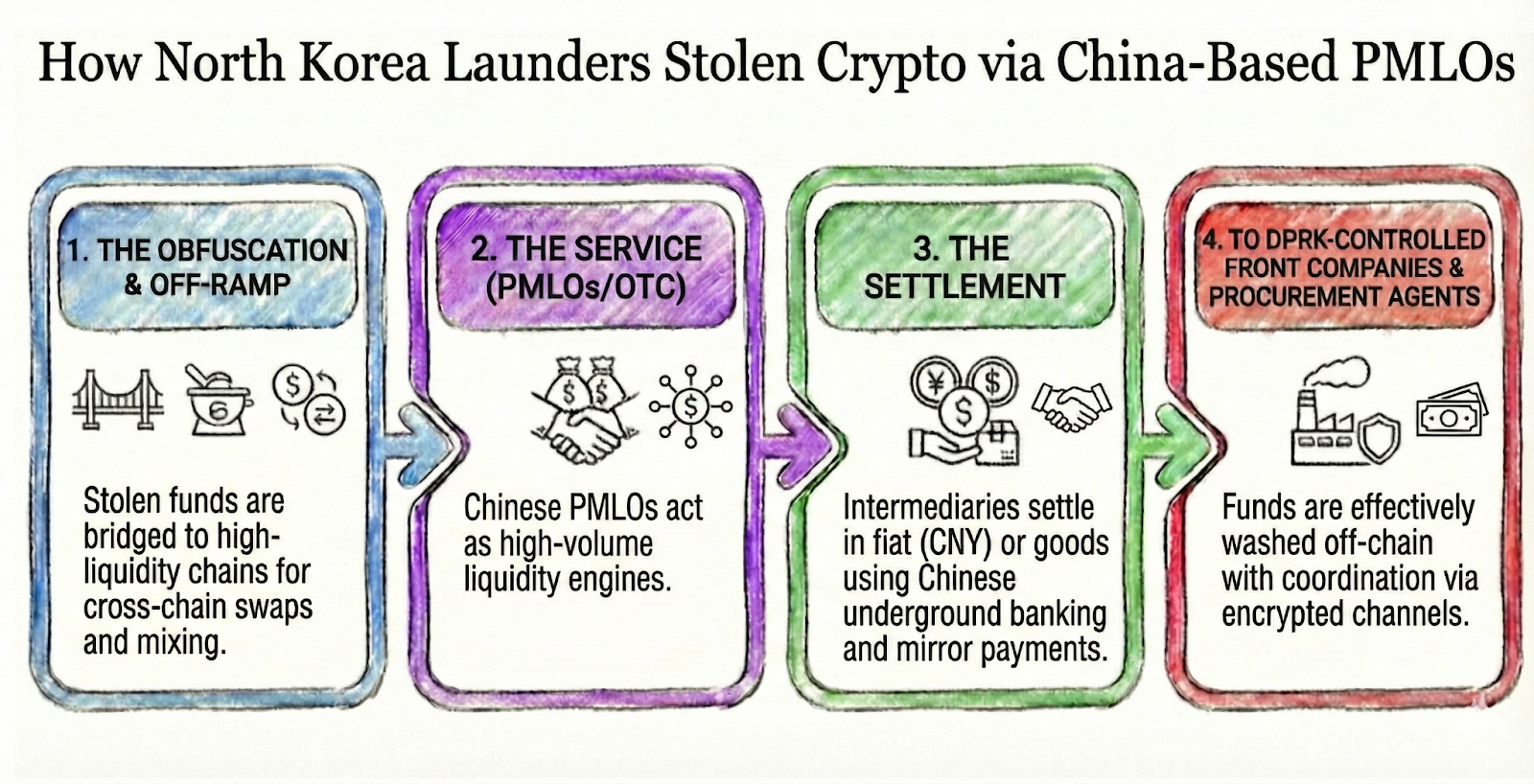

The "Chinese Laundromat": subcontracting the cleanup

Perhaps the most critical evolution TRM has observed in the last few years is the industrialization of the cleanup phase. While North Korea had leveraged established Chinese OTC networks for years—particularly after authorities sanctioned its traditional facilitators in 2020 — what formerly was a subcomponent has now become the primary infrastructure obfuscation for liquidation.

Following Western sanctions against mixers including Tornado Cash and Sinbad in 2022 and 2023 respectively, North Korean threat actors adapted their laundering playbook. The laundering process is now both substantially more complex and effectively subcontracted to a sophisticated, high-volume network of Chinese intermediaries.

The off-ramp

Stolen funds are bridged to high-liquidity chains (primarily Tron and Bitcoin) and deposited into nested exchanges or wallets controlled by high-risk OTC desks. Stablecoins — especially USDT on Tron — have become the preferred intermediary asset, providing deep liquidity and fast settlement that make large-scale off-ramping easier to mask.

In the Bybit case, for example, the stolen funds were rapidly pushed through intermediary wallets, DEXs, and cross-chain bridges, with hundreds of millions of dollars moved within days. It was these Chinese laundering specialists who handled the complex process of cross-chain swaps and mixing illicit Bybit proceeds. TRM previously assessed that the Chinese actors entered the process only at the end during the liquidation phase; we now understand, however, that the entire laundering and liquidation process was sub-contracted to Chinese specialists.

The service

Professional Money Laundering Organizations (PMLOs) — primarily Chinese shadow-banking brokers with operational footprints across Southeast Asia — purchase hacked crypto at a discount and provide off-chain settlement. These organizations function as high-volume liquidity engines for North Korea, clearing stolen assets through mirror payments, goods-based settlement, and informal cash networks.

The settlement

TRM has observed that these intermediaries settle transactions in fiat (primarily CNY, Chinese yuan), goods, or direct payments to North Korean front companies. Settlement often occurs entirely within Chinese underground banking and commercial networks — through mirror payments, trade-based offsets, or goods transfers — completing the laundering cycle without any exposure to formal banking rails.

This laundering cycle effectively washes the funds before they ever touch the North Korean financial system. It also explains why laundering volume remains high despite Western sanctions: increasingly, the “cleanup” isn’t happening on the blockchain at all. Instead, it’s being coordinated by Chinese underground bankers via channels such as WeChat and similar OTC settlement networks.

Compliance implications: elevating exchange security standards

For crypto exchanges and financial institutions building on blockchains, this pivot collapses the traditional silos between cybersecurity and AML risks. Static blocklists are no longer sufficient; detection and prevention now depend on detecting full laundering patterns — such as the AVAX-to-BTC-to-Sinbad pipeline —often while assets are briefly touching benign rails and seemingly clean addresses.

Sanctions/AML

An effective sanctions program must go beyond static blocklists to typology-driven detection of North Korean laundering stacks (bridges + mixers + casinos + OTC), not just “known mixer” exposure.

Nested service monitoring

Enhance due diligence and transaction surveillance rules on counterparties that sit in known laundering pipelines, specifically “nested” exchanges. These smaller platforms often rely on liquidity while acting as the primary entry point for the illicit Chinese OTC network. If a nested partner cannot produce robust KYC for their own flows, consider conditional holds or offboarding.

Real-time monitoring

Multi-chain tracing should be considered a baseline requirement; auto-flag and queue flows that match North Korean-linked cross-chain patterns (e.g., AVAX→BTC→Sinbad→TRON USDT), even when assets briefly touch “benign” rails.

Intelligence-driven controls

Pair hardware-secured key storage with tiered withdrawal policies, behavior-based velocity limits, and privileged-access segmentation to raise the cost of hot-wallet compromise.

Conclusion: the industrialization of theft

North Korea’s pivot is more than a change in targets; it represents the state-sponsored professionalization of crypto-crime. North Korea has moved from opportunistic hacks to an industrialized supply chain: sourcing initial access from social engineering specialists, extracting funds via infrastructure attacks, and liquidating assets through a subcontracted network of Chinese shadow bankers.

North Korea’s crypto theft operations function as a structured, state-directed revenue system — a coordinated apparatus that blends cyber activity, intelligence support, illicit finance infrastructure, and partnerships with overseas facilitators. These efforts are designed to generate capital at scale, support national priorities, and circumvent international sanctions. Responding effectively requires coordination across governments, financial institutions, and technology partners with the same level of organization and speed.

As stablecoins grow in liquidity and crypto payment rails become increasingly integrated into real-world commerce, the environment for tracing and containing stolen assets becomes more complex. The laundering networks that North Korea relies on — including Chinese brokers, underground banking channels, and mirror-payment systems — now provide an obfuscation layer more effective than many traditional crypto-mixing tools. This architecture enables stolen funds to move rapidly across borders, chains, and intermediaries, underscoring the need for a unified, cross-border strategy to disrupt the financial infrastructure that makes these operations so effective.

{{horizontal-line}}

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

1. What is North Korea’s role in cryptocurrency theft?

North Korea is the leading nation-state actor in crypto theft. In 2025 alone, TRM attributes over USD 1.5 billion in stolen crypto to North Korean-linked operations, including major hacks targeting centralized exchanges and custodial service providers.

2. How have North Korea’s tactics evolved?

North Korean actors have shifted from exploiting DeFi protocols and bridges to targeting centralized platforms. Recent attacks focus on compromising developer environments and gaining access to wallet infrastructure through social engineering, phishing, and malware-laced “job application” files.

3. What is the “Chinese Laundromat”?

The “Chinese Laundromat” refers to a network of OTC brokers, underground banks, and money transmitters that launder stolen crypto on behalf of North Korea. These intermediaries operate across Southeast Asia and specialize in high-volume off-chain settlement, often in Chinese yuan (CNY).

4. How do North Korean threat actors launder stolen crypto?

After initial theft, funds are rapidly moved through cross-chain swaps (e.g. AVAX → BTC → Tron USDT), nested exchanges, and DEXs. Laundering now often occurs entirely off-chain via brokers who convert crypto into fiat or goods using informal financial networks.

5. Why are centralized exchanges being targeted?

Centralized exchanges present single points of failure — such as hot wallets or key orchestration systems — that can be exploited through social engineering or software supply-chain compromise. These infrastructure-level attacks yield significantly higher returns than traditional DeFi exploits.

6. What can compliance teams do to detect North Korea-linked activity?

Teams should adopt intelligence-driven detection strategies, including:

- Typology-based monitoring of cross-chain laundering patterns

- Risk-based screening of nested exchanges and OTC flows

- Real-time, multi-chain transaction tracing

- Hardware key protections and withdrawal velocity controls

7. Has sanctions enforcement disrupted North Korea’s laundering tactics?

Not effectively. While mixers like Tornado Cash and Sinbad have been sanctioned, North Korea now relies on more complex, off-chain laundering infrastructure. Their laundering stacks are harder to trace and no longer rely solely on on-chain mixers.