How We Made Airflow Development 20x Faster

Key takeaways

- Know your users: The best tool is the one people actually use. Design for their convenience, not yours.

- Absorb complexity so users don't have to: Low-friction tools get adopted faster.

- Optimize for the common case: Handle the common case exceptionally well over handling all cases adequately.

- Fast iteration compounds: Both humans and AI agents benefit from tight feedback loops.

{{horizontal-line}}

At TRM, we use Apache Airflow to run complex data workflows. Today we have hundreds of Airflow DAGs, millions of tasks, and dozens of developers working on those DAGs. At this scale, it's vital to have robust developer tools and patterns. We like to move fast, so iteration speed is of particular importance.

The problem

We use isolated dev Airflow environments at TRM. The behavior of our DAGs is sensitive to environment-level configs such as Airflow variables — so every dev gets their own environment to avoid stepping on each other's toes. Historically, we deployed these dev environments remotely and in the same manner as our prod environments. When we used managed Airflow, both prod and dev environments would be managed. When we switched to self-hosted Airflow, we used the same Helm charts for prod and dev.

This made sense on paper:

- Easy to extend existing deployment methods for the dev use case

- Trivial to scale up remote environments to meet resource needs

- Identical architecture between dev and prod

However, the developer experience had two major pain points:

- Execution environment: Devs could not run Airflow commands locally. Every interaction required uploading DAG code first, then SSH-ing to the Airflow cluster or using the managed solution's interface to actually run anything.

- Sync tax: Every change required uploading DAGs to remote storage and waiting for Airflow to pull it down. Frustratingly, different types of changes were subject to different refresh rates.

To solve for these issues, we needed to make it possible to work with Airflow locally, then run Airflow itself locally.

Enabling local development

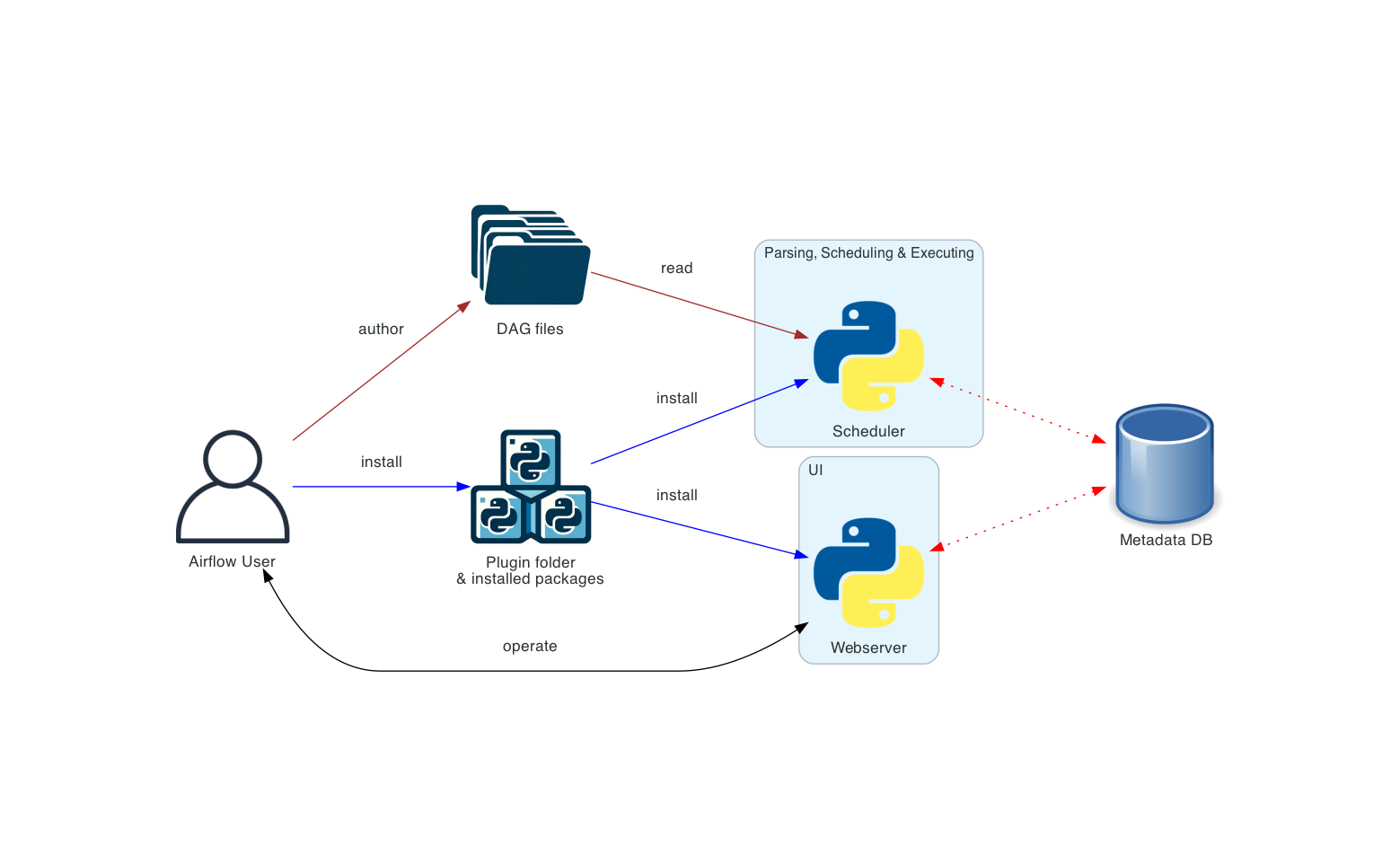

The first step was enabling local Airflow commands without needing to actually run Airflow. If you don't need to schedule tasks, Airflow only requires a few things:

- A database to store metadata

- Environment configuration, like Airflow configs, variables, and connections

- Python dependencies required by Airflow and your DAGs

A default Airflow installation uses SQLite, which already solves for (1). And we have default variables, connections, and pools files for remote Airflow deployments, which mitigates (2). And Python virtual environments can solve for (3). The main challenge is providing all of these in a user-friendly way.

We package this in a single script that we call env_airflow.sh.

Key design decisions

The script is structured as follows:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

ENV_NAME="airflow-local-v1.0"

ensure_conda_installed()

if env_is_corrupted $ENV_NAME; then

delete_env $ENV_NAME

fi

if ! env_exists $ENV_NAME; then

provision_env $ENV_NAME

fi

activate_env $ENV_NAME

setup_pythonpath()

set_airflow_config()

init_or_migrate_db()

exec "$@"Users invoke it like so:

$ ./env_airflow.sh airflow --helpThe core design philosophy is that the user never has to think about environment management. Managing Python installations, updating dependencies, and activating the virtual environment are handled transparently by the script. In exchange, the user pays a small tax and invokes the script with every Airflow-related command.

To sweeten the deal, the environment is self-healing. Corrupted environments, which can be caused by interrupted installations, are detected and rebuilt. When dependencies are updated, we bump the environment name to trigger a rebuild on the next invocation. This keeps everyone's environment up-to-date over time, as pulling the latest code also picks up updates to the environment. Upgrades to the Airflow version, though infrequent, are detected and trigger any necessary database migrations.

All dependencies live in a Conda environment, which is isolated from the user's system. We utilize Conda's excellent ecosystem of open-source projects like mamba and conda-forge. There are other tools, most notably uv, which can manage Python versions and packages. We chose Conda because it can install non-Python packages as well. This will be important later.

We deliberately do not configure a DAGs folder. For commands relating to DAGs, the Airflow CLI's default behavior is to parse everything in the DAGs folder before executing the desired command. That would take several minutes at our scale. Instead, users specify exactly which DAG they're working with via the --subdir (or -S) flag.

Usage

Now Airflow DAG code can be easily explored with a local Python shell:

$ ./env_airflow.sh python

Python 3.11.14 | packaged by conda-forge | (main, Oct 22 2025, 22:56:31) [Clang 19.1.7 ] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> from helpers.trm_constants import PRODUCTION_ENVIRONMENT_NAME

>>> PRODUCTION_ENVIRONMENT_NAME

'prod'

{{how-we-made-airflow-development-20x-faster-callout-1}}

We can also validate DAGs on command:

$ ./env_airflow.sh airflow dags reserialize --subdir path/to/my_dag.dag.py

# This is the simplest Airflow command which parses the specified DAGs.

# It also serializes them to the DB, but this is a harmless side effect.We can even set breakpoints in DAG code using pdb to debug import errors or inspect state.

Finally, we can execute arbitrary tasks:

$ ./env_airflow.sh airflow tasks test \

--subdir path/to/my_dag.dag.py \

my_dag \

my_task \

2026-01-01The -m flag can be added to automatically open the debugger when an uncaught exception is raised. Manual breakpoints work too.

This was helpful for iteration, but didn't solve all our problems. CLI workflows are not for everyone. It's much easier to tailor your Airflow variables, connections, and pools with the UI, as is running multiple tasks or DAGs. Airflow power users were happy to use the CLI, and so were new hires who didn't yet have established dev cycles with Airflow. But for many devs, having a UI was non-negotiable.

Running Airflow locally

Devs won't adopt new tools just because you claim they're great. To have an impact, our local Airflow solution needed to be as frictionless as possible. For TRM, this meant virtualization was not an option — no virtual machines or containers. Most of our Airflow devs do not use virtualization in their day-to-day work. Forcing them to install a container runtime or hypervisor would be too much friction.

Instead, we made tradeoffs specific to TRM's workloads. The majority of our Airflow tasks make API calls to managed services via Python SDKs. The work happens in the cloud while Airflow simply orchestrates that work. Therefore we can prioritize ease of setup over architecture parity. A consistent Python environment is all we need to sufficiently mimic prod.

Sound familiar? env_airflow.sh does exactly this. It manages a Python environment that is consistent across machines. On top of this, we built run_local_airflow.sh, which manages an Airflow instance that is consistent across machines. It spins up the necessary Airflow components on the host without using containers or VMs, and shuts them down when the user terminates the process.

Piecing things together

To make the leap to a full Airflow instance, we need to run:

- A scheduler to schedule tasks

- A webserver to serve the UI

- Any additional components required by the executor, e.g. a queue for

CeleryExecutor - A Postgres or MySQL instance to store metadata, as SQLite does not work well with concurrent workloads

Airflow provides a helpful command called airflow standalone which can run (1) and (2). And LocalExecutor is sufficient for local development, meaning we don't need anything for (3).

That leaves (4) as the primary challenge. We didn't want the user to install and manage additional tools. That includes databases. And this is where Conda shines — it can install more than just Python packages.

Adding Postgres

Like our Python environment, Postgres needs isolation from the user's system. We add it as a Conda dependency in env_airflow.sh for a fresh installation. We set a unique data directory via PGDATA to avoid collisions with existing Postgres installations, pick a non-default port, and use --no-psqlrc when running psql to ignore user-specific configurations.

run_local_airflow.sh manages the full lifecycle of the Postgres database. Initializing the database, performing any migrations, and shutting it down are all handled transparently without the user lifting a finger.

Once Postgres is ready and configured, the script runs airflow standalone to start the scheduler and webserver. When the user terminates the script, it shuts down all Airflow and Postgres processes.

Making the UI more responsive

With Airflow now sharing the same filesystem as the developer, the sync tax has been eliminated. But this alone doesn't make iteration fast. Airflow DAG changes can be classified in two ways:

- Changes to DAG properties (e.g. the list of tasks, the relationships between them)

- Changes to task properties (e.g. what a given task actually executes)

With local Airflow, changes to task logic are picked up as soon as the task runs. This is because Airflow parses the DAG from scratch to execute a task. In contrast, if I add or remove a task from the code, this change will not be visible in the Airflow UI until Airflow's DAG processor re-parses the DAG file.

To make DAG changes visible faster, the DAG processor needs to parse more frequently. But this requires more host resources. And since we have hundreds of DAGs, it's prohibitively slow for Airflow to parse them all. We solve this problem by requiring devs to specify which DAGs they are working with via regex. For remote environments we only sync DAG files which match this regex. Remote DAG files which don't match the regex are deleted so that Airflow doesn't process them.

Deleting local files is not acceptable, so local Airflow needs a different mechanism to prune the DAGs. We tried several approaches and settled on might_contain_dag_callable. This optional Airflow function indicates whether a given Python file contains DAG definitions. We define one such that Airflow only processes DAG files matching the regex. This allows us to run the DAG processor more frequently, which in turn helps the UI reflect DAG changes faster.

Despite these internal complexities, using local Airflow is simple:

$ ./env_airflow.sh ./run_local_airflow.sh "dag_regex1" "dag_regex2"That’s it!

Life without containers

Foregoing containers is an unconventional choice. Most companies using Airflow at our scale focus on how they can use containers more. Many local Airflow setups outside TRM use Docker Compose or even local Kubernetes, making it easy to define the environment and reproduce it on dev machines. And Kubernetes Pod Operators are a popular way to separate the concerns of Airflow developers from those managing the Airflow deployment. In fact, for some companies Kubernetes Pod Operators are the de facto standard for task execution.

At TRM, most of our Airflow developers are data scientists and data engineers for whom containers are not a required core competency. Therefore we have chosen not to require knowledge of containers to work with Airflow. Of course, we encourage developers to use containerization where appropriate. Workloads requiring high resource usage, for example, should use Kubernetes Pod Operators. But these cases are uncommon and most of our developers won't encounter them.

Prioritizing a frictionless experience over reproducibility comes with consequences. Historically, Airflow was designed to be deployed on x86 machines running Linux. Other architectures and operating systems are supported thanks to the Python ecosystem, but there will always be gaps across different platforms. Our dev machines are MacBooks running Apple Silicon, so as the maintainers of local Airflow it's our responsibility to discover and bridge those gaps.

Beyond platform differences, optimizing for ease of use also means constant attention to detail. There is a long tail of improvements that are needed to make a great developer experience. A sample:

- Detecting expired cloud sessions on startup and prompting re-authentication

- Prompting to confirm the DAG list, catching regex typos before Airflow starts

- Handling edge cases with startup and termination, e.g. starting Airflow while it’s already running in another terminal

- Making fresh

env_airflow.shinstallations faster

Such improvements might seem minor individually, but they separate a working prototype from a tool people actually want to use.

Impact

By the numbers:

Iterating on task logic, which is the most common change type, is now instant. Iterating on DAGs, less common but often more complex, is 20x faster. And the cost of a dev Airflow environment dropped from USD 200/month to USD 0.

Today, most Airflow developers at TRM exclusively use local Airflow. There are still cases where remote Airflow is appropriate — low spec dev machines, workloads needing elevated permissions, or long-running jobs — but these are the exception, not the rule.

What’s next

LLM agents are rapidly improving at coding tasks. What if an agent could own the entire Airflow development loop? We built a prototype at an internal hackathon. In our final demo we planted a bug in an Airflow data pipeline and asked the agent to fix it. It booted up local Airflow, ran the task, checked the output, fixed the code, and repeated until the output was correct. The agent did not require human intervention — only context on how devs at TRM perform this type of loop. It needs polish, but it's a promising start.

An unintended benefit of local Airflow is that the agent doesn't need to wait for DAG code to sync. Loops that are fast for humans are fast for agents too. Good documentation, test harnesses, and dev environments are only more important with the advent of LLM agents.

Beyond development, we're interested in using agents to assist with production Airflow. Many of our on-call responsibilities revolve around keeping our mission-critical Airflow pipelines healthy. While it's too early to give an agent write permissions for a production environment, we're excited to explore how agents can simplify Airflow operations for humans.

Join our team

I developed local Airflow during a holiday code freeze after getting tired of waiting for my DAG code to sync. I'm proud to work somewhere I’m empowered to identify pain points and solve them, even outside of my area of responsibility. If you like working on hard problems and moving fast, we're hiring!

{{horizontal-line}}

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

1. Is it really so bad to use containers/virtual machines?

In our case, probably. Developers — many of whom have never touched containers — would need to install Docker, authenticate to the registry, etc. And even then, Docker file mounts on macOS are quite slow today. Unexpected and unpleasant things can happen, like running out of Docker disk space, that would sour the experience. Virtual machines can have better file mount performance, and tools like Vagrant can help manage them, but a hypervisor still needs to be installed.

It’s hard to convince busy developers to change patterns they’ve used for months or years, and even harder if they also need to install a bunch of stuff to do it.

2. Will this ever be open-sourced?

Maybe someday! Our scripts are tailored for TRM right now. The concepts are portable, so feel free to give these ideas a shot.

3. What would you do differently if starting over?

I would use telemetry to identify the developers for whom local Airflow did not work out of the box much earlier. There were edge cases, mostly around permissions or environment quirks, that prevented the tool from working for some. Many of these were reported quickly and fixed, but in some cases the developer just went right back to using remote Airflow. They were also unlikely to recommend it to their teammates. Lesson learned: even when optimizing for low-friction, expect edge cases to surface and identify them without developers needing to come to you.