Incautar, Quemar, Bloquear, Reemitir: Entender las herramientas legales detrás de la recuperación de criptoactivos

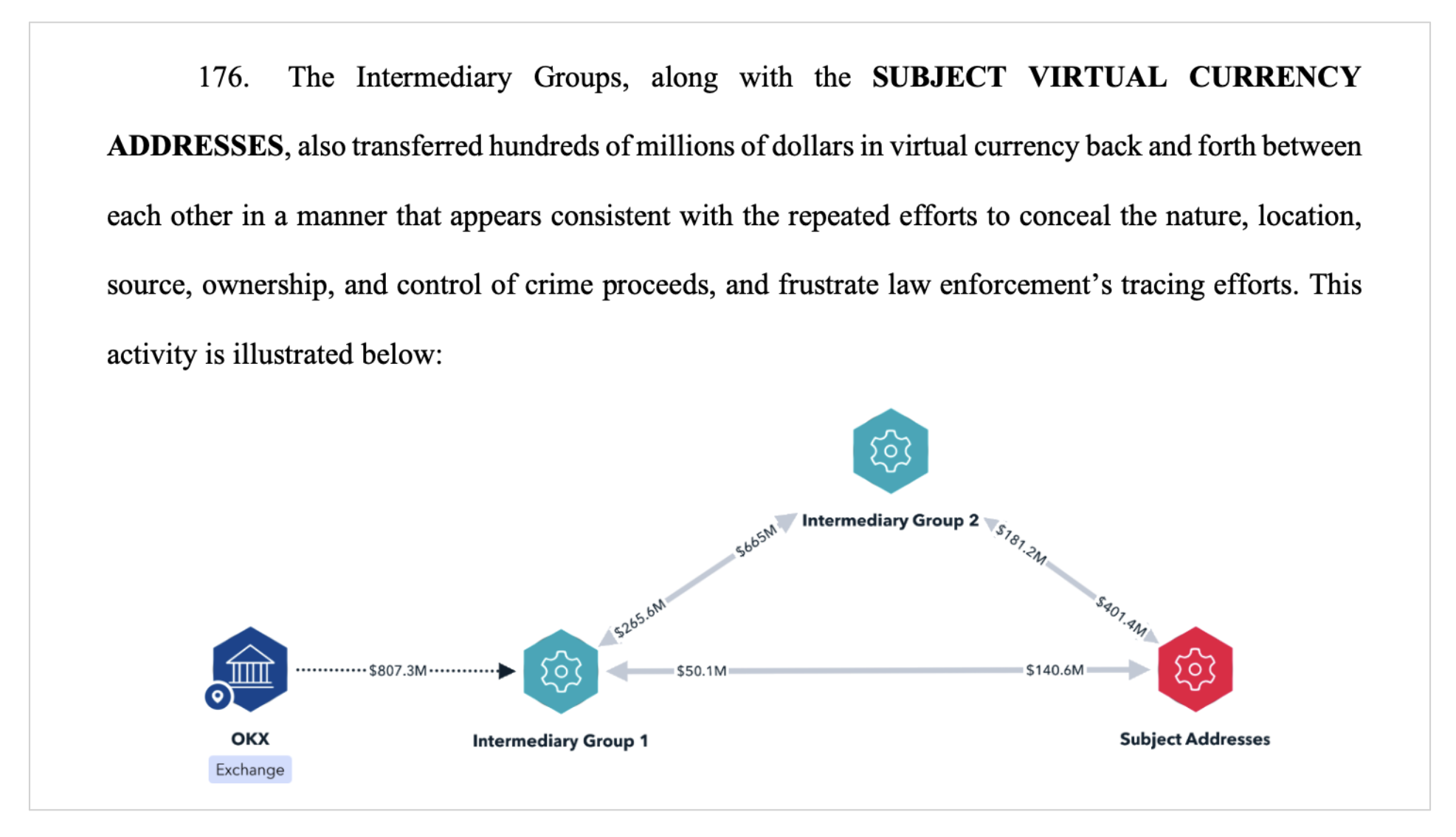

El 18 de junio de 2025, la Fiscalía del Distrito de Columbia presentó una demanda civil de confiscación de más de 225 millones de dólares en criptomoneda. Según la denuncia, los activos estaban vinculados a una estafa internacional de inversión en criptomoneda que afectaba a cientos de víctimas. La investigación, dirigida por el Secret Service EE.UU. y FBI, aprovechó la Inteligencia en Blockchain de TRM, como se detalla en la denuncia, para rastrear los fondos ilícitos a través de complejas redes de blanqueo y, en última instancia, identificar los monederos asociados para su incautación legal.

Esta acción, que representa la mayor incautación de criptomonedas vinculada a un fraude de inversión en la historia de EE.UU., ilustra cómo el rastreo de activos digitales, combinado con la incautación y las herramientas técnicas relacionadas -congelación, quema y reemisión- pueden servir como instrumentos para la aplicación de la ley y la restitución. El caso también coincide con el creciente interés legislativo en la codificación de tales mecanismos, sobre todo a través de la Ley GENIUS, que autoriza a las autoridades federales a dirigir la incautación o destrucción de stablecoins ilícitas.

Definiciones: ¿Qué significa incautar, congelar, bloquear, quemar, reemitir o decomisar activos digitales?

Los términos utilizados en las acciones de aplicación relacionadas con los activos digitales a menudo se solapan, pero tienen significados jurídicos y técnicos distintos. Las siguientes definiciones reflejan cómo se entienden estos conceptos en los procedimientos judiciales y en la práctica:

Aproveche

Acción autorizada por un tribunal, normalmente en virtud de leyes de confiscación civil o penal, por la que las fuerzas de seguridad toman el control de un activo digital. En muchos casos, esto implica ordenar a una bolsa, emisor o proveedor de monedero que transfiera los activos a una dirección controlada por el gobierno. La incautación también puede producirse cuando el gobierno obtiene credenciales para transferir el activo directamente.

Congelar / bloquear

Mecanismo que restringe el movimiento de un activo, generalmente sin eliminarlo de la blockchain. Los emisores, los smart contracts o las plataformas de custodia pueden bloquear o congelar direcciones o tokens para impedir nuevas transacciones. Estos términos suelen utilizarse indistintamente.

Quemar

Proceso técnico que destruye un token enviándolo a una dirección irrecuperable. La quema de un token lo retira de la circulación de forma permanente y suele llevarla a cabo el emisor, a menudo siguiendo instrucciones legales o en respuesta a una orden de incautación.

Reedición

La emisión de nuevos tokens por un emisor de stablecoin u otra plataforma en una cantidad equivalente a los fondos quemados o congelados. Esto puede utilizarse para transferir valor a carteras gubernamentales para su recuperación o para devolver fondos a las víctimas en procesos de restitución. Aunque se utiliza habitualmente en la práctica, el concepto de reemisión no está definido actualmente en la legislación.

Decomiso

Mecanismo legal por el que el gobierno obtiene de forma permanente la propiedad de bienes considerados relacionados con actividades delictivas. El decomiso puede ser civil (contra el activo) o penal (tras la condena), y permite a las autoridades disponer de los activos, reutilizarlos o devolverlos en función de las conclusiones judiciales.

Contexto legal: ¿Qué autoridad de destrucción de activos se propone en la Ley GENIUS?

La Ley GENIUS (Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for US Stablecoins), aprobada por el Senado el 17 de junio de 2025, propone una autoridad legal para la incautación y destrucción de activos digitales ilícitos. En concreto, la Sección 5(a)(2) establece:

"El Secretario del Tesoro y el Fiscal General, actuando conjuntamente, pueden tomar las medidas apropiadas para incautar o hacer que se queme cualquier stablecoin o activo digital relacionado utilizado en una violación significativa de la ley de sanciones, la ley penal federal, o cualquier orden de decomiso emitida por un tribunal de jurisdicción competente."

Este lenguaje autoriza a las agencias federales a ordenar la incautación o quema de stablecoins asociadas con infracciones significativas, incluyendo la evasión de sanciones y esquemas criminales. La ley refleja un esfuerzo por alinear las herramientas legales con las técnicas de aplicación nativas de blockchain.

En particular, la Ley GENIUS no menciona ni define la reemisión - un mecanismo que algunos emisores de stablecoin han utilizado para facilitar la recuperación de activos y la reparación a las víctimas. En la práctica, la reemisión suele producirse tras un evento de quema, en el que los fondos ilícitos se vuelven inutilizables, y permite a los emisores acuñar una cantidad equivalente de tokens para devolverlos a los monederos controlados por el gobierno o directamente a las víctimas. Su omisión en el estatuto puede reflejar la naturaleza específica o discrecional del proceso. Sin embargo, la ausencia de un reconocimiento estatutario claro también podría reducir la probabilidad o la coherencia de los esfuerzos de recuperación de las víctimas en futuras acciones de aplicación.

DOJ Caso práctico: Rastreo e incautación de activos en un decomiso de 225 millones de USD

La denuncia por decomiso de junio de 2025 ofrece un ejemplo de cómo se utilizan en la práctica los cinco mecanismos: congelación, incautación, quema, reemisión y decomiso. Los investigadores utilizaron Analítica de blockchain para trazar el movimiento de fondos a través de cientos de miles de transacciones que implicaban monederos e intercambios intermediarios. En muchos casos, los depósitos se enrutaron a través de docenas de transacciones a través de la cadena de bloques -a menudo a través de cadenas de pelado e intercambios entre cadenas- para ocultar su origen y llegar a monederos de consolidación vinculados a redes de fraude.

En un caso, un antiguo director general de un banco de Kansas, S.H., malversó 47 millones de USD del Heartland Tri-State Bank y transfirió más de 3 millones de USD a un esquema de confianza en criptomoneda. Utilizando el rastreo LIFO, los fondos fueron rastreados a través de 17 direcciones de monedero hasta una de las 22 cuentas sospechosas. El rastreo adicional mostró que los fondos se consolidaron posteriormente en direcciones de blanqueo junto con otros fondos de las víctimas.

La denuncia cita múltiples ejemplos en los que los ingresos procedentes de víctimas de fraude se depositaban en direcciones conectadas a redes de blanqueo de mayor envergadura. Los intercambios de criptomonedas fueron fundamentales para que las fuerzas de seguridad pudieran identificar a los titulares de las cuentas y rastrear los flujos de fondos. Sin embargo, la denuncia no especifica si se quemaron o reemitieron activos, sólo que se rastrearon fondos y se vincularon a actividades delictivas a efectos de decomiso.

¿Qué mecanismos técnicos y de cooperación existen para ayudar a restituir los bienes a las víctimas?

En los ecosistemas de stablecoins, la incautación y la quema dependen a menudo de la cooperación del emisor. Tether y Circle, los mayores emisores de stablecoins, por ejemplo, han congelado y quemado tokens a petición de las fuerzas de seguridad en casos anteriores. En algunos casos, los tokens quemados van seguidos de una acuñación equivalente de nuevos tokens, reemitidos al gobierno o, en los esfuerzos de restitución, a las víctimas.

Sin embargo, la función de reemisión no está estandarizada entre blockchains o tokens. Depende de la arquitectura subyacente, el proceso legal y las políticas del emisor. Como tal, incluso cuando se autoriza la quema -ya sea a través de embargo legal u orden judicial- la reemisión puede no ser automática o asegurada.

¿Por qué es tan importante la reemisión?

A medida que aumenta el uso de activos digitales en el fraude, la evasión de sanciones y la ciberdelincuencia, la claridad en torno a las herramientas de aplicación de la ley es cada vez más importante. La Ley GENIUS ofrece el primer texto legal propuesto que autoriza a los organismos federales a incautar y quemar stablecoins ilícitas. Sin embargo, la ausencia de cualquier referencia a la reemisión deja abiertos interrogantes sobre cómo pueden restituirse a las víctimas los activos confiscados.

La reemisión -el acto técnico de emitir un valor equivalente para reemplazar los tokens quemados o confiscados- ya ha desempeñado un papel en algunos esfuerzos de recuperación anteriores. Permite a los emisores de stablecoins y a las autoridades garantizar que los tokens quemados no se destruyan sin más, sino que el valor equivalente se destine a fines públicos, incluida la restitución.

Aunque la reemisión no está actualmente codificada en la ley, sigue siendo una herramienta operativa en los casos en que la cooperación del emisor y la capacidad técnica lo permiten. A medida que evolucione la legislación, estas distinciones -incautar, congelar, bloquear, quemar, reemitir- pueden convertirse en los elementos constitutivos de un marco jurídico más completo para la recuperación de activos digitales y la financiación de una reserva estratégica.